It is impossible to write a history of night climbing–because there is no such history.

–Whipplesnaith, The Night Climbers of Cambridge, 1937

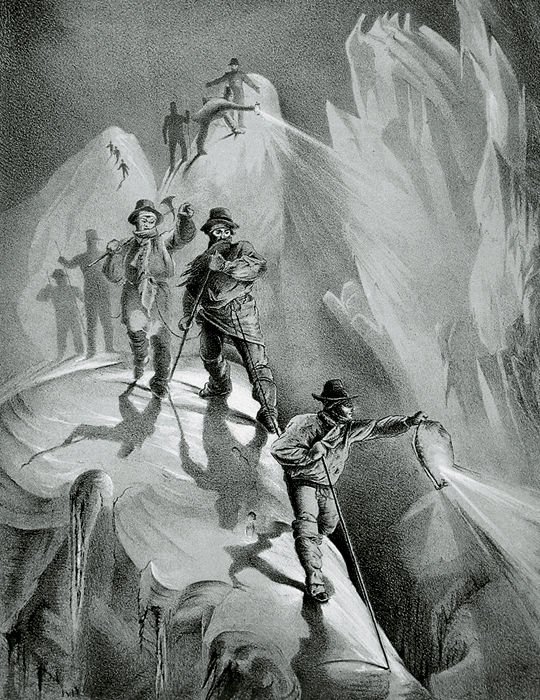

DUSK DRIFTED ACROSS THE SNOW-LIT TOWER OF THE WEISSHORN like a sea of phosphorescence. As the edges of crevasses flared up in shafts of moonlight, the British climber Geoffrey Winthrop Young imagined they were dragons’ teeth. The gurgling rivulets, grinding ice and chiming shards seemed to swell into a wild din of wordless shouts and eerie atonal music. “It is a ghostly clamour,” he recalled in his 1927 memoirs, On High Hills, “that night-shouting of glaciers, sufficient to account for the superstition that a spirit life haunts their white dead spaces.”

By then, the once-popular belief that supernatural creatures inhabited the Alps had dimmed. In 1903 Young’s compatriot Douglas Freshfield had decried the onslaught of “monster hotels” and “coal-smoke” engines that replaced the old myths as new railways delivered hundreds of tourists to high cols (Round Kangchenjunga). It was as if the mysteries were fading from the noonday peaks, reflecting the spread of industrialization and the decline of faith in the valleys. In 1917 the German sociologist Max Weber famously declared “the disenchantment of the world.”

And yet, during his evening alpine rambles, Young found himself dreaming of stern processions of stone trolls, floating specters of imaginary mountains and silver notes of inaudible song. “Why are these nocturnes so deeply etched?” he wondered. Decades later, he could recall with crystalline precision a boyhood winter walk over Styhead Pass in the English Lake District: how the night sky mirrored across the white surface of the hills, “And to a rhythm as of chanting, the star, the snow and the silence are reborn.”

LIKE MANY, PERHAPS, I FIRST BECAME a night climber by stealth and by accident. During my school years, under the clouded-orange reflections of city lights, my friends and I explored the pale gothic granite of a theological library and traversed the ice smears that glowed down a red brick wall. Later, in Wyoming, my climbing partner and I became unintentionally benighted near the top of Mt. Owen. As the last blue-violet rays of dusk glistened down a rain-wet chimney, I took three short falls on a brass micronut, only to have it rip out when I clambered onto the next ledge, my fear ringing in the dark. While my partner led on, a giant rat-like animal seemed to nibble at my feet, disappear into the shadows, re-emerge above us, jump over my partner’s head and scurry headfirst down the same slippery rock I’d struggled so hard to climb.

Was it a snafflehound? A shared hallucination? Beyond the weak beam of my headlamp, the night flowed up the final crevice, cold and thick as black water, spilling out, at last, onto the summit and beneath the stars. The moon was setting. Cast against the distant, ashen plains, a flawless silhouette of the Teton Range flickered and began to fade like a vanishing map.

SOMETIME AFTER THAT EXPERIENCE ON MT. OWEN, I came across a Climbing article by Chad Shepard about night soloing in the Sierra. “A glimmer catches my eye,” he wrote, “moonlight has overtaken the face. The rock is reborn in the delicate light…. A pure right-now instant, ropeless on perfect glacial patina.” And I started to wonder what other unseen marvels might await, high in the dark hills, beyond the last streetlamps of town. For years since, I’ve climbed at odd hours of the night and filled my bookshelves with stories of other sleepless wanderers.

In The Summits of Modern Man (2013), the historian Peter Hansen describes the early exploration of the Alps as a by-product of the Enlightenment, quoting Leslie Stephen, the grand pundit of the Golden Age: “The history of mountaineering is, to a great extent, the history of the process by which men have gradually conquered the phantoms of their own imagination.” But there’s also another history in which some climbers have striven to re-create those ghosts–not in their literal shapes of dragons, goblins and fairies, but in a deeper, more symbolic form, seeking, instead, the wildness, uncertainty and awe that we often associate with nightfall and pre-modern times. As Hansen says, “We stand on something like a threshold and get tugged in both directions”–toward the light and toward the dark.

A true history of night climbing would, I’ve realized, be impossible to write: too many nocturnal ascents have taken place in secret. Nonetheless, a few scenes of its visible lore, blended together, hint at a countercultural narrative of climbing, one that isn’t about the advance of information, the conquest of territory or the domination of the natural world. But about something other, more elusive, that each of its protagonists has sought amid the shadows of stone chapel spires, moonlit north faces, Arctic winters and archaic dreams. One might imagine them, mostly unknown to each other, yet bound across decades, abilities and countries by similar impulses: a league of journeyers into night.

THE NIGHT ITSELF WAS ONCE A REALM that seemed nearly as uncharted as the heights. For centuries, as Wolfgang Schivelbusch and Paul Bogard recount, darkness swept across cities and towns like a black tide, rippled only faintly by the glow of campfires, hearths, torches, candles and oil-lantern flames. Modern forms of artificial lighting didn’t emerge until the Industrial Revolution generated the desire to illuminate vast factory halls, extending the workday well into the evening. Over the nineteenth century, first gaslights and then electric streetlamps began to shine in European and North American cities, increasingly dimming the natural light of the stars (Disenchanted Night, 1995; The End of Night, 2013).

As daily existence became more mechanized, controlled and polluted, the mountains seemed, more and more, like a last refuge of wildness and (for some) true night. By the mid-twentieth century, the French alpinist Gaston Rebuffat wrote in Starlight and Storm, “In this modern age, very little remains that is real. Night has been banished, so have the cold, the wind, the stars. They have all been neutralized: the rhythm of life itself is obscured.” In the Alps, a climber could still immerse himself in the primeval brilliance of night skies. No longer a “spectator” or “robot,” he could regain his place as part of the spinning Earth and heavens: “Electricity may have banished [the stars] from man’s life in the valley, but on high places, their golden crystals are a part of his very being.”

Other climbers found faint, ironic remnants of mystery on the still-shadowy roofs of cities at night. In 1900 Young secretly composed The Roof-Climber’s Guide to Trinity, the first of a series of anonymous guides to nocturnal ascents high on the buildings of Cambridge University. Afraid of getting caught, a later author explained, “We operated like a secret society, a brotherhood of the night.” Whipplesnaith, the pseudonymous chronicler of The Night Climbers of Cambridge (1937), evoked a wildwood of dusky pillars and startled birds. The spires of King’s Chapel formed leafy patterns against the full moon. Palms pressed on sloping holds, a climber might look down at a void of black air. “Those who have seen these things,” he wrote, “will remember the poetry it has taught them.”

WALKING INTO THE NORTH WOODS OF VERMONT in winter, I find the starlight can be enough to see, mirrored across the countless tiny crystal facets of snow-encrusted branches and frost-lined rock: a faint silver illumination of the earth. At the base of a tree-darkened route, I turn my headlamp on, and a frozen waterfall ignites like a glass lantern. Partway up, I peer into an ice cave, and the inside flares a livid blue. The lamps of houses in the valley far below seem as distant as other galaxies. Here, the play of dimmer lights and deeper shade re-enchants a world already transfigured by snow. Some of my escapes from town–like those of many night climbers–are, paradoxically, aided by a small amount of electricity. But anything outside that headlamp’s circle reverts to an unimaginable wilderness of shadow and sound.

It’s easy to forget how recent modern forms of night climbing are–how little the early pioneers could often, actually, see. As night overtook Young’s party during an eighteen-hour traverse of the Dent Blanche, the guides lit the lanterns one by one. For a while, the five men whirled about, untangling the rope, and then they moved up and down the icefields, bobbing and flickering like a string of fireflies, searching for imperceptible tracks. When Young fell to his armpits in a hidden crevasse, ice fragments clinked into deeper, sightless depths.

For much of the last century, pitch-darkness at high elevations inspired a much-greater dread than it does now. As the historian Maurice Isserman points out, the word benightment can mean “either being caught out after dark, or being ignorant/cursed.” During the 1922 Everest attempt, when Mallory and his companions descended toward the North Col under a moonless sky, they were grateful the air was still enough for the flame of their only candle lantern to catch. In 1963, as Willi Unsoeld and Tom Hornbein climbed down from the twilit summit, the 3-D-cell batteries of their early, clunky headlamp died. “Our light was like a cigarette glowing in the dark,” Hornbein recalls, “shedding no light within a few seconds.” After the inevitable forced bivouac, Unsoeld kept the toes he lost to frostbite in a glass jar.

Over the next decades, as headlamps became more reliable, climbers became freer from their dependence on the sun and moon–able to stretch out longer summit bids and continuous single pushes. Habitual predawn starts meant less time exposed to the hazards of sun-warmed seracs and slopes. In the 1980s, Erhard Loretan and Jean Troillet reversed the old order of Himalayan ascents entirely with their “night-naked climbing”: soloing nonstop by night, and resting only briefly (if at all) by day. By moving fast without bivy gear, Troillet believes, they avoided the long-term altitude effects of 8000-meter peaks. “It’s not the same mind at night,” he adds, “to be alone, so quiet. When I look back on my life, I was born under a beautiful star. My mother went to church to light candles. Maybe that’s what saved me.”

ALONE BEFORE SUNRISE, on approaches to the Tetons, I tried to suppress my fear of bears, like a child holding her breath by a graveyard: What’s that shudder in the underbrush? That reflection of two lights, like eyes? Only the distant cars driving across the plains. Only a deer’s gaze, blinking like foxfire between the trees. Nightfall restores a primal awareness, each sense heightened by the potential or illusion of danger, turning shifting leaves into predators, but also awakening minds to unexpected vision. Tommy Caldwell once told the writer Matt Samet that he thought El Capitan was “easier” at night, because the shadows of his headlamp made small footholds seem larger. Soloing by pure moonlight in the Evolution Basin, Samet recalls how his own eyes adjusted to the natural radiance reflecting off white granite, until his perception seemed to expand to an almost-metaphysical “seeing.”

LONG AFTER MOST RANGES were at least partly explored, the murk of polar winters held out the promise of vast dreamscapes and long nights for the imagination to brood. In 1967 Art Davidson and his partners planned the first winter ascent of Denali as a “journey into an unexplored land. No one had lived on North America’s highest ridges in the winter twilight.” Under the drifting moon, the white ridges flowed into “estuaries of darkness.” The Northern Lights sparkled with prismatic fire. On the way down from the top, trapped in a snow cave, barely alive, he repeated a line from a Dylan Thomas poem: Light breaks where no sun shines (Minus 148, 1970). Since then, Masatoshi Kuriaki has made a dozen winter and early spring Alaskan expeditions, including the first winter solo of Mt. Foraker. Despite the -100 degrees F wind chill, he has found joy in the contrast between illumination and shadow: the moon against the sky, the stars over the hills. “Even a tiny candle light in a cold dark snow cave at night gave me warmth, mind and body,” he says.

One of the oldest paradoxes of night climbing is how it echoes, thus, ancient, archetypical myths of traveling through darkness toward some keener, purer light. In the 1975 cult-classic essay “Night Driving,” the climber and skier Dick Dorworth described blazing through the deep-space-like emptiness of night-shrouded highways on endless road trips until exhaustion and loneliness seemed to break down the habits of urban life and the illusions of the ego, and a long-lost Eden glimmered on an ever-receding horizon, amid the green fragrance of sagebrush, with the “sharp sorrow of memory-feeling…. How do we get back to it? Where did it go?”

Around a decade later, fueled by punk nihilism, Mark Twight plunged into the dark alcoves of his mind and the “black depths” of high-risk alpinism, fighting through images of dead partners, mildewed walls and hallucinatory rats, seeking to tear away the “monotony and alienation of industrialized life” and to regain his “animal self.” At last, he wrote, “from death, I learned to live, to want to live, to be capable of doing so without making a mess or mockery of living. I learned to love” (Kiss or Kill, 2001). Confronted with a night that reminds us of mortality, many of us feel an increased passion for existence that swells to encompass all living and nonliving things, as if we could enfold the very universe itself. From knowing the numbness of the coldest hours, we seem to experience, briefly, in all its original, blazing intensity, the slow, life-quickening warmth of a pale and ash-gold dawn.

AS I HIKED DOWN FROM SPRUCE PEAK in Vermont, one late-summer night, the batteries of my headlamp failed, and I lost my way. Darkness drifted through the humid air, more green than black, dripping with moisture from a dense canopy of leaves. Somewhere below me, I knew, the ground must fall away, to where the cliffs I ice-climbed in winter were now a jumble of wet grey rock. To avoid stepping over some invisible edge, I crawled under snapping branches, following the damp moss of a stream, down small boulders as gnarled as the roots of trees. For the first time, on this familiar hillside, I began to relearn its intricate forms by touch.

In The End of Night, Paul Bogard reports, “Two-thirds of Americans and Europeans no longer experience real night–that is, real darkness–and nearly all of us live in areas considered polluted by light.” Within the developed world, he explains, relatively few people can still summon up a memory of what a true night sky looks like, when, according to astronomer John Bortle, the Milky Way is bright enough to cast faint shadows on the earth.

But while some regions have now been designated as “Dark Sky Reserves,” there’s an equal need to conserve similar endangered spaces in our minds. The ever-present glow of computer, tablet and phone screens can begin to seem, at worst, like the floodlights of some dystopian prison, a relentless, distracting glare of communication shining into nearly every nook. In contrast, the quiet focus and beauty of nocturnal ascents reminds us of the value of keeping certain moments and places in the dark. As Ueli Steck writes in this issue of Alpinist, some of the most profound experiences are ones that can never be fully shared. To allow more room for them, we might need to reclaim what the nineteenth-century historian Jules Michelet once called, in response to that initial spread of gaslight, the “darkness into which thought can withdraw…, [the] shadowy corners in which the imagination can indulge its dreams” (Le Peuple, 1846).

For all the time we’ve spent as climbers honing the strength and agility of our bodies, perhaps we’ve lost track of how necessary it is to train our eyes and minds for wonder, to find a better balance between enlightened uses of technologies and timeless practices of awe. In 1953, back in the streets of Paris and dreaming of the Alps, Rebuffat forgot where he was. He peered up through the incandescent fog of lamps toward the thin strip of sky, looking for stars–signs of cold, clear weather and firm slopes. Such recollections of mystery can descend anywhere, sifting back through the dull light of midday, as radiant and dark as snow falling in a night wood. Perhaps that’s one reason why moon- and star-rise appear, to us, so alluring, transmuting even the smallest wild spaces into strange and unknown lands–that hope, that in an instant, all the world and all ourselves might change. Burn, if only for an instant, with a clear, sharp inner fire. As Rebuffat declared, “It is time to light the lantern and start out.”