Thoughtful, articulate and/or humorous responses to our print or web articles will be considered for publication. Write to us!

Email:

katie@alpinist.com

Snail Mail:

Alpinist Editorial Staff

PO Box 190

Jeffersonville, VT 05464

For The Squishy Bunny Bunch

And then I see a darkness.–Bonnie “Prince” Billy

TWIGHT ALWAYS WROTE FROM HIS BLACK SIDE, and I’d give him shit for that because I knew he held more white light within him than almost anyone else did. He told me that his gods spoke to him through the music, punk music. We lived the darkness and the intensity of the descent, used it as a tool of ascent engendering the dark in each other, yet neither of us took it to the bottom as Kevin Doyle did. He wrapped his strong arms around it and boldly wrestled with it all the way down. Not everyone survives that match.

The Brotherhood. The bonds that I formed with those men on the sides of our mountains are the strongest in my life. On the cold flank of Nuptse, at dusk, 2002, the last really big mountain that I tried, I blurted out to Steve House, “I love you man.” And it was so true. You come to love your brothers and that may be the real gift of alpinism: it opens the human heart, tries it mightily, but opens it. Seems to me that The Squishy Bunny Bunch are holding to the light and may be beyond this advice, but I will give it anyway for it has cost me dearly–tell the people that you love that you love them. I cannot relate how important that is.

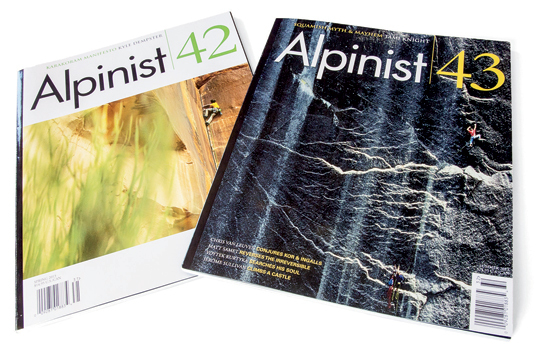

I applaud the spirit of ascent that Kyle Dempster shared in “The Torch and The Brotherhood” (Alpinist 42); it warms my soul to see evolution toward the light. “Everything I know, I know only because I love,” wrote Leo Tolstoy.

—Barry Blanchard, Canmore, Alberta

Time to End the Inequality

IN RESPONSE TO “The Sharp End,” Alpinist 43: Much has been said and done in the past few years to “help” the Sherpa community. Many of the people spearheading these efforts are of pure heart and pure intention; they truly want to make the world and the Sherpa community a better place–from a nonprofit called The Juniper Fund that strives to help families whose primary income earners have died on Everest, to The Khumbu Climbing School, which focuses on getting frontline Sherpas the technical skills they need to survive in one of the most hostile environments on earth.

While these are important and noble efforts, such endeavors are reactive to the problems we now face. What if we, as an industry, could ask a more-proactive question, challenging our belief that what we’re doing now is the only way it can and should be done? Today, outdoor recreation has become a multibillion-dollar industry. From gear manufacturers to sponsored athletes to guiding companies, we support 6.1 million jobs in the United States, not to mention overseas (Outdoor Industry Association report, 2012). No longer can we say we are a “mom and pop” business culture, with little economic or social impact, just “mountain folk out to make a good living and have a good time.”

Ever since the first Everest attempts, the Western mindset has generally been one of seeing the Sherpas as employees, instead of potentially equal business partners. This lack of equality was seemingly accepted, however grudgingly, until this generation of Sherpas, whose fathers and mothers worked hard in the mountains to provide a better life for their children, some of whom have been able to attend private schools in Kathmandu or even receive scholarships for international universities. Returning to the mountains with an increased global awareness, these young Sherpas see the disparities more clearly. Many now realize that they can find their own clients and break the cycle of being beholden to bigger, foreign companies for work. In return, some of the larger operators have grumbled that these Sherpas are “unsafe,” “irresponsible,” and “unethical.” But these are the same workers whom the operators rely upon to fix the ropes, set the camps and carry the detritus of clients up and down the hill.

The inequality is apparent, yet the means to fix it is not. What if our industry offered Sherpas a different sort of education? One that includes finance, language, technical and ethical leadership? A kind of Outdoor Industry MBA? Many foreign outfitters will see this suggestion as a threat, and they should, because it will affect their bottom line, yet here is the truth of the matter: Change is coming whether they want it to or not; the ultimate question will be, who will strive to become part of the solution instead of continuing to be part of the problem.

—Luis Benitez, Vail, Colorado