Wart Hog In the era of Soviet “mass alpinism,” climbers behind the Iron Curtain were generally limited to ascents within Communist borders, often at big alpine camps or in state-sanctioned competitions. Back then, the only available ice protection was a fat, spiral-toothed peg produced by state-regulated firms according to a standard design. Ice axes had a hexagonal hole in the bladed end to match the piton’s upper shaft for easy twisting removal. Although the screw hammered nicely into soft glacial ice, it was too thick and blunt to place easily (or at all) in dense water ice. And so it fell to steep-ice aspirants behind the Iron Curtain to invent a solution.

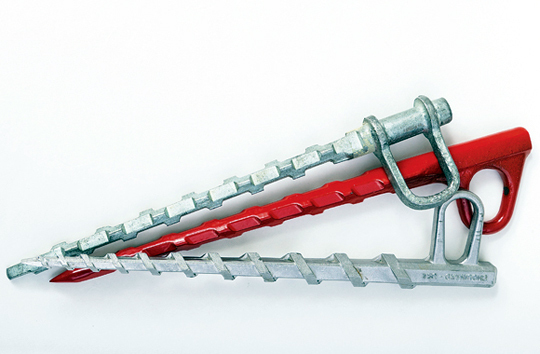

During the mid-1960s, the Czech climber Milan Doubek handmade a few slimmer carbon-steel, pound-in, screw-out ice pitons. As he tested his prototypes, he discovered that they didn’t shatter or overly displace water ice as the original pegs had. Since the sale of such “useless” items was unfeasible in the Eastern Bloc, he showed them to a West German climber, Hermann Huber, during a 1966 climbing meet at Cesky Raj. In 1967 Huber’s company, Salewa, started manufacturing the SpiralZahnHaken–spiral-toothed piton, based off Doubek’s designs. The original model was made from a steel rod, with teeth and notches painstakingly machined into the form of a spiral shaft.

The SpiralZahnHaken was never a big seller, but it placed better in dense ice than the Soviet ice pegs or the Western options of the time did. Chouinard Equipment began importing Salewa gear in May 1970, and Yvon Chouinard eventually christened the piton “the Wart Hog.” In the 1975/1976 catalogue, the company introduced its own version, with sharper spiral ribs for greater holding power. Because neither Huber nor Doubek applied for a patent–it was too costly–other manufacturers began producing the Wart Hog as well.

By the mid-1970s, Alastair Walker recalls, Scottish climbers typically carried two or three Wart Hogs. The compact Highlands mica schist often required creative protection, and Wart Hogs could be hammered into its thin cracks, screwed into ice-filled fissures or pounded into frozen turf. In 1999 Stephen Reid placed a Wart Hog in turf after twenty feet of unconsolidated snow on Parallel Gully A at Lochnagar. He then had to run it out to 150 feet and dig a small scoop in the snow for an anchor. Despite Reid’s instructions not to fall, his partner slid off just below the Wart Hog. The piece helped reduce the strain enough so that Reid wasn’t torn from his precarious stance–saving both their lives.

Although modern ice screws have proven their superior reliability on pure ice, Wart Hogs retain a cult following in places like the Scottish Highlands and the Tatras Mountains (along with the local Wart Hog-like “grass needle”) for their usefulness in frozen turf. Wart Hogs have also demonstrated their mettle on chalk routes. In 1981 Mick Fowler, Andy Meyers and Chris Watts became the first to try ice gear on the White Cliffs of Dover, with the first ascent of Dry Ice (Chalk III). The Wart Hogs they brought took less than a minute to hammer into the softer, seawater-logged chalk at the cliff base, but much longer on the drier stone up high. “I’ve never tested them,” Fowler says, “but I know they have held some big falls.”

Today, Reid’s Needle Sports is the last known vendor of Wart Hogs (now “Warthogs”), which are produced by an English manufacturer. Their designs never received the EU’s Personal Protective Equipment certification because, Reid says, “frozen turf cannot be replicated in the laboratory, and as a climber has no way of knowing how deeply frozen a piece of turf is, the results would be irrelevant.” Nonetheless, two random screws tested from the latest batch bent over at a whopping 25 kN–and failed to break.

As for Doubek, he fled Czechoslovakia in 1968 when Soviet tanks invaded his country, and he found work at a Salewa factory in West Germany. In 1972 he perished in a collapsing ice cave during the last day of filming Der Blitz–Inferno am Mont Blanc, a movie that recreated Walter Bonatti’s epic on the Central Pillar of Freney. But the Wart Hog and Doubek’s legacy live on–thanks to the unique adaptability of this unusual piece of gear to some of the vertical world’s most esoteric terrain.