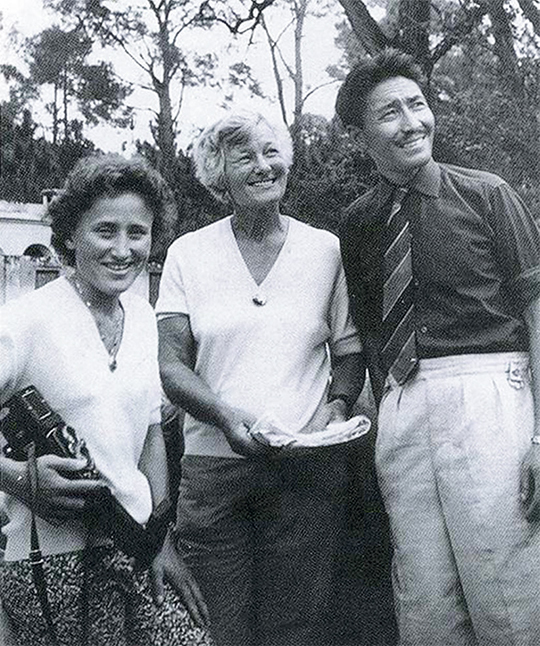

[Photo] Claude Kogan collection

1953, ZANSKAR HIMALAYA: A small shadow of a woman moves slowly over a drape of white. The summit cone of Nun glows, no longer distant, its 7135-meter apex still untouched. Panes of ice lie scattered like thin glass, across drifts so soft and deep that French alpinist Claude Kogan can find nothing secure for her crampons to hold. At the other end of the rope, Swiss missionary Pierre Vittoz follows her winding tracks. Because Kogan is the lightest, she has volunteered to go first. If I have to fall with one of the wind slabs, she thinks, Pierre will at least have some chance of catching me. Neither of them speaks, afraid to awaken each other’s doubts. She knows that the success of the expedition depends on them. She knows that even if they turn back, they could still die. Again and again, she sinks the entire shaft of her axe into airy snow.

A mist rises, concealing all that lies behind her: the debris of the seracs that destroyed Camp III; the memories of the avalanche that injured three of her companions, Bernard Pierre, Michel Desorbay and Ang Tharkay Sherpa, now recovering in lower camps. But when the summit reappeared through the clouds, crystalline and bright, she’d still felt called by it. Everything seemed simple and clear, she’ll later recall. Perhaps the mountain was created for me. Or was I created for it?

She has labored hard to reach this point, cutting steps into steep black ice between camps I and II, fixing ropes for the team to haul loads. Bernard considers her a “miracle,” a slender, five-foot-tall “slip of a woman… worth the same in the mountains as a man.” Only a year ago, he’d begged her to slow down as she simul-climbed ahead of him along the thin white ribbon of a crest on Salcantay in the Andes of Peru. She’d felt overwhelmed by a desire, then, almost to run, as though the summit might vanish in the air before she could catch it. She’d promised herself, after her husband died in 1951, to make the first ascent of his dream mountain.

Late that evening on Salcantay, she’d stood alone outside the team’s high camp, staring back at the mountain they’d just climbed. Moonlight quivered across the snows. In her account for the Belgian Alpine Club, she wrote, “The summit seemed to tremble in the night.” Something about Salcantay reminded her of a sphinx: “Had the mountain been an initiation?… It had proposed a riddle to me. But even the fact of having climbed it didn’t let me guess its answer.” Now, on the highest point of Nun, she feels, for an instant, a sense of total and eternal joy. The mist spins. In an Alpinisme article, she’ll write, “I was the warrior relieved of his heavy armor, and I felt light, ethereal…” She picks up a few small stones for their teammates, and she and Pierre begin the long descent down the ice-shattered slopes. Only six years later, she will disappear, along with Claudine van der Stratten and Ang Norbu Sherpa, beneath an avalanche on Cho Oyu. The last words in her journal, written by candlelight, will read: To pursue, always higher, toward the summit. Fate is thus made.

————————————————————————

FOR A TIME, Claude Kogan was among the most famous female climbers, featured in magazines like Elle, known as “the highest woman in the world.” During the decades after her death, she became increasingly obscure, more frequently recalled as the leader of the failed “women’s expedition” on 8201-meter Cho Oyu–rather than the successful first ascensionist of Nun, Salcantay and Ganesh Himal. In a 1965 book, Lady Killer Peak, British reporter Stephen Harper (whom Kogan had banished from base camp) insisted on “a verdict that even the toughest and most courageous of women are still ‘the weaker sex’ in the White Hell of a blizzard and avalanche-torn mountain.”

Decades later, French climbing journalist Charlie Buffet marveled at how long it took for him to recognize the significance of Kogan’s story. Like others of his generation, he’d grown up immersed in the classic books of the Golden Age of Himalayan Climbing, tales of armies of men battling storms and snow to make first ascents of the world’s highest peaks. In the introduction to his 2003 biography of Kogan, Premiere de Cordee, Buffet recalled:

For us, the history was simple: the conquerors had fulfilled their contract; they’d planted their flags on all the most important summits…. Drawn on the maps in the colors of empires, the peaks formed a constellation of miniature colonies: French Annapurna, British Everest, Italian K2…. Beneath the din of national hymns, it took almost fifty years to hear a little music that was different…. Claude Kogan had been one of the best alpinists of the Fifties…. A woman built like a bird, she’d climbed…with Belgians, Americans, Swiss, Nepalis, Brits…. She’d installed doubt in the spirit of the conquistadors. Her success had unsettled those of the alpinists, the machos and the masochists who had forgotten the uselessness in their passion. Her death for a long while put things back in their place.

————————————————————————

THERE’S A TENDENCY to mythologize the Fifties in Western culture, to imagine it as a time when the boundaries between men’s and women’s lives were clearly drawn. Female characters are largely absent from most Himalayan stories of the era, often appearing only as wives and mothers faithfully awaiting the heroes’ return. Nonetheless, metaphors of summits also resonated deeply with women after the upheavals of World War II–a time when they, too, had left their homes in large numbers to work, to serve and even fight. And for a few female climbers like Kogan, the postwar years became a time of bold exploration in mountain literature and in the hills.

Gwen Moffat, who’d been an army driver, felt disoriented by the declaration of peace: “Now there was only the bewildering prospect of demobilization and beyond that…nothing.” In 1945, when she pulled her vehicle over to offer a man a ride, he shared stories of his vagabond climbing life. “The very fact that it seemed to be the quintessence of everything I had ever wanted,” she wrote in her autobiography, Space Below My Feet (1961), “adventure, freedom, rejection of authority–carried the knowledge that, once committed, I should find it terribly difficult to go back.” Eight years later, Moffat had become Britain’s first female professional mountain guide.

War widow Nea Morin spent the Fifties making all-female ascents in the Alps, often with her daughter. In her memoir, A Woman’s Reach (1968), she recalled, “To the final question, ‘What do you get out of it?’ I imagine the answers must be much the same for women as for men…. Returning from these experiences everyday life appears clear-cut and in focus.” And in a 1951 novella, One Green Bottle, Elizabeth Coxhead imagined a working-class woman who finds an expanded freedom leading hard routes up rain-dark crags in Wales. “You can’t think how grand it is,” she cries out to her female partner, “feeling the rope run out behind you. It’s like flying.” Spend more time with old journals and anthologies; pull neglected volumes from library shelves; and you start to see so many other stories of women adventurers emerge–the way that, as your eyes adjust to the dark, you begin to perceive more and more faint stars.

[Photo] Nea Morin collection

————————————————————————

IN 1954 THREE MEMBERS of the Ladies’ Scottish Climbing Club–Monica Jackson, Elizabeth Stark and Evelyn Camrass–gazed at a map of Nepal, tracing the 500 miles of its northern border, the rippling patterns of high snows. They’d never been to the Himalaya before. Another climber pointed to a bend in an obscure line of peaks, the Langtang and the Jugal Himal. “You know,” Douglas Scott said, “nothing much has been done there.”

A few years prior, British explorer Bill Tilman struggled in the same region through snowdrifts and monsoon clouds. Even the lower flanks of the Jugal Himal seemed inaccessible, blocked by deep gorges and swollen rivers. But when the women arrived in the nearest village in 1955, a local man, Nima Lama, led them along a convoluted path to the entrance of the range. Beyond a barrier of stony needles, unclimbed summits emerged from the mists, sharpening into white and gold spires. Maps of previous explorers–made from distant vantage points–proved inaccurate. “I felt as though a sudden splendid chord of music had rung out across the sky,” Stark recalled in Tents in the Clouds. They chose a 6706-meter dome for their objective, climbing up the center of a heavily crevassed glacier, around and over walls of blue-green ice.

It was not, of course, “the first all woman’s Himalayan expedition,” despite the billing in the press, for male Sherpa climbers–including Mingma Gyalgen and Ang Temba–helped establish the new route up what the team named “Gyalgen Peak.” As the climbing historian Kerwin Klein points out, a modern reader might compare such ventures, instead, to something of Eric Shipton and Bill Tilman’s style: relatively low-budget, lightweight teams wandering at will into scarcely charted ranges, making first ascents of whichever peaks allured them most.

Between World War II and the early 1960s, members of similar, female-led expeditions explored 6000-meter mountains in India’s Kullu region: Jean Low, Eileen Gregory, Joyce Dunsheath, Hilda Reid, Frances Delany of Britain; Ang Dolma, a Sherpani; S. Hosokawa, K. Hamanaka, M. Okabe, K. Hara, Y. Sugiura and Y. Okugawa of Japan, to name only a few. During a decade that emphasized large sieges of 8000-meter peaks, a smaller-scale approach to lower summits made their journeys appear marginal. Over the years, their deeds have mostly faded into scattered lists of names, constellations of quiet stories. Nevertheless, something shifted. Gradually, more women started to image themselves into pictures that once seemed to belong only to men–roped together in the cold, thin air; cutting their own steps past dazzling ice spires and azure crevasses, up endless slopes of snow.

IN 1952 British novelist Daphne du Maurier, best known for her romance Rebecca, published a collection of stories that included a mysterious and largely forgotten climbing tale, “Monte Verita.” A young bride, Anna, leaves her husband behind and continues alone to the summit of Monte Verita–“The Mountain of Truth,” although villagers warn her of some unusual, perhaps supernatural, danger for women there. She has the look of one who has been “called,” a local man says. She’s also the strongest climber of the story, the one who seems to understand best the meaning of ascent. After she vanishes, the narrator goes to search for her, following a steepening rock ridge as a sliver of moon rises through the mist. “It was as though I walked alone on the earth’s rim,” he recalls, “the universe below me and above…. This was not mountain fever in my blood, but mountain magic.” Above a narrow gully, the twin summits of Monte Verita blaze in opalescent light. What he encounters ahead, echoes Anna’s insistence that “those who go to the mountain must give everything.”

More than six decades later, I find myself, like the narrator, filled with longing and fear–at a sense of what it might mean to remain in that perfect moment of transcendence forever, all boundaries of self lost in frozen wonder. “For the first time in my life,” the narrator declares. “I looked on beauty bare…. This indeed was journey’s end. This was fulfillment…. I stood there staring at the rock-face under the moon.”

————————————————————————

IT SEEMS ODD TO THINK, in 2015, that we might still need to defend the idea that women can be creative, exploratory alpinists. During the past few months alone, Anna Pfaff, Rachel Spitzer and Lisa Van Sciver became the first climbers to summit Tare Parvat, a 5577-meter mountain they chanced upon, while wandering in Zanskar. Natalia Martinez participated in the first ascent of remote and labyrinthine Mt. Malaspina, then the highest of North America’s named but unclimbed peaks.

Yet stories about women that seem to gain the most attention remain those of first female ascents or female records on the world’s most famous mountains–news more easily consumed because it fits familiar frameworks–rather than their first ascents in less well-mapped places. There’s still a tendency to treat women’s adventures as a side branch of climbing history, to forget the ways they influenced its overall evolution. By restoring them to the main narrative of mountaineering, we begin to realize how rich and contradictory the pursuit has always been. Seemingly vanished memories run quietly as underground glacial streams, ready to emerge again, far from their origins, retaining all the brilliance of high snows.

These October evenings, I’ve gotten in the habit of pacing the country roads near the farmhouse where I live, letting words of dusty books play out in my mind, summoning images of past mountaineers. The rain-swollen creek grows louder, as if echoing the cracks and groans of glaciers. A low cloud, pressed up against the dark crests of the hills, rises like the dream of a mountain. Like all ice climbers, I feel the early stirrings of the frost as an intimation of magic. I picture the glow of white slopes and gullies, the moments when familiar ground sinks far beneath my feet, and the possibility of some new and unimagined way of being might appear. And as the wind lifts and the mist rolls, the edges between the land and the air blur–until I feel as though I’m walking inside the night sky.

It is then that I stop and gaze up at all that blaze of starlight. I think of a fabled mountain under a flood of moon. A woman gazing at a sphinx-like summit. An author, paused at her desk, writing, Those who go to the mountain must give everything. The small shadow of a climber.

[With additional thanks to: Janice Sacherer, Tashi Sherpa, Norbu Tenzing Norgay, David Stevenson and Kerwin Klein. For other stories of Fifties women climbers, see “A House of Stone and Snow,” Alpinist 49. –Ed.]