This Sharp End first appeared in Alpinist 38–Spring 2012.

How can I express all the thoughts and emotions that swirl in my head, Hayden, when you are halfway around the world on a big route? I remember my own days up high, the feeling of lightness as the earth drops away, the moments of pure grace when nothing matters except the next move–setting a foot just so, feeling the solid thunk of an axe, the calmness of my heart and mind. Everything I needed was right before me.

I know that’s what you’re searching for, but it’s not always what you get.

For I also recall the deafening fatigue of climbing too many hours without stopping, the dry throat and the aching belly, the paralyzing fear of a long runout. The bad anchors. The close calls with storms, rockfall and avalanches. The anxiety of being days away from safety, wondering whether the next pitch will go, searching for a bivy site or just a place to sit for a few hours, knowing that the only way out is over the summit and down an unfamiliar ridge.

You’ve gotten all that and more since you left home.

We’ve talked about being in tune and in balance, with our partners and ourselves, with our ambitions and hopes, with the weather and the mountain spirits. Yet luck or fate can always intervene with these hopeful aphorisms, sometimes in our favor and sometimes not.

On January 16, I learned of the death of Jack Roberts on Bridalveil Falls near Telluride. Only a week earlier at the Ouray Ice Festival, he and I had traded lighthearted stories about aging and injuries, about our wives’ unwavering sympathy for our quirks, and about how much we still enjoyed climbing despite our multiplying aches and advancing weakness. We spoke about getting on a route together. Although we’d known each other for years, and I’d written the foreword to his Colorado ice-climbing guide, we’d never roped up.

You would have liked Jack. His smile conveyed an energy that made you want to head out to the nearest crag and get after it. In Ouray, he was as happy as I’d ever seen him. And then, inexplicably, he was gone.

Dinner was subdued that evening. I was depressed about Jack’s death. Mom was worried about you. Do you remember when she told me that if I ever taught you to ice climb, she’d kill me? She figured that ice climbing was the gateway drug to alpinism. Fortunately, you learned it on your own.

We knew you were in the mountains, but we hadn’t heard anything for several days. Then a post from Colin Haley appeared on Facebook: “Today we got to watch history being made…. Hayden Kennedy and Jason Kruk made the first fair-means ascent of the SE Ridge of Cerro Torre…[in] about 13 hours to the summit from a bivy at the shoulder.”

Someday, you’ll understand the intense relief we felt on reading those words.

Your ascent of the Southeast Ridge must have been exhilarating: a faultless line with a great partner on that iconic gold and white spire. For me, and for many others, this climb embodies the highest ideals of boldness, difficulty, commitment and self-reliance–the foundations of alpinism. And when you cleaned a third of the 360 bolts on the Compressor Route, you made a courageous first step in restoring Cerro Torre to its rightful place as one of the most demanding and inaccessible summits in the world. I never would have had the guts to take that step myself, even in my best days.

You and Jason knew that a number of people would disagree with that act. Yet the depth and the nastiness of some of the criticism has both surprised and disillusioned you. On your return to El Chalten, you were accosted and threatened by local Argentines, even by a few you considered your friends. You were detained and questioned by the police. You’ve been lavishly praised and roundly condemned online and in print.

The controversy over the removal of Cesare Maestri’s bolts has overshadowed not only your own visionary climb but also the free ascent of the Southeast Ridge by David Lama and Peter Ortner a few days later. It has obscured an astonishing season in Patagonia, which included, among other great efforts, a weeklong traverse of the Cordon Adela to Cerro Torre by Max O’Dell, Juan Raselli and Agustin Raselli; a creative new ice route on Torre Egger by Bjorn-Eivind Artun and Ole Lied; and a major new linkup on Fitz Roy by Scott Bennett and Cheyne Lempe.

Remember one thing: all this noise is someone else’s story, not yours. People will try to pigeonhole you with their words, but you aren’t defined by what others think, only by what you know and by who you are, in your heart and mind. On Cerro Torre, you thought and acted with conviction and passion, making one of those decisive, spontaneous and honest gestures that can come only out of the uncensored soul.

When you head out in the future, other people will have expectations of you. Those notions will reflect their needs, desires, aspirations and fears. As best you can, clear your mind of the chatter. Don’t think about how your life or climbs will look to anyone else. Make choices based on your values, your analysis, your intuition and your dreams.

The story of the Southeast Ridge is one of the distance between our ideals and what we are willing to sacrifice to live up to them. As alpinists, we should strive to reach our dream summits with a minimum of means, leaving the least trace of our passage. Even in 1970, when Maestri placed all those bolts with the aid of a gas-powered compressor, his route was regarded as an atrocity, a “desecration,” as Mountain Magazine called it at the time. Yet as a community we’ve offered our implicit acceptance of the Compressor Route for over forty years. Through our collective laziness, complacency or greed, we’ve allowed it to become an institution.

Chopping the bolts was a reminder that we need to abide by what we say we believe in. For making that decision, some will call you and Jason heroes. Others will call you villains. Don’t buy into either narrative.

By now, you’ve climbed all the Torres, expanding your sense of the boundaries of the world. I can imagine you gazing out over the icecap from those remarkable summits, into the white light and the blue shadows, dreaming of adventures still to come.

And yet, perhaps, in those moments, you also remembered Bean Bowers, who’d spent so much time in this range. A little over a year ago, during a casual day of backcountry skiing in Colorado with you and a few other friends, he’d broken his femur. You got a sense, then, of how serious any accident can be in the wild. Because of the fall, Bean’s doctors discovered he had cancer. All too soon, at age twenty-one, you faced your first encounter with the death of a peer, someone young and vital cut down by sudden illness.

After Cerro Torre, you and Jason returned safely to Base Camp at Niponino, only to learn that another friend, Carlyle Norman, had been severely injured by rockfall on nearby Aguja Saint-Exupery. A rescue effort was already under way, but Jorge Ackerman, Colin Haley, Rolando Garibotti and Pep Masip were turned back by rockfall and storm. Carlyle died alone. She remains entombed among the same mountains you’ve come to love. You told me later: “It was the highest of highs followed by the lowest of lows.”

An awareness of mortality prompts us to focus on what’s important: developing a strong community of family and friends; engaging in work that stretches us intellectually, creatively and emotionally; understanding that no matter how often we’ve erred or compromised in the past, we must always try to reach again for the highest ideals.

This February, not long after you came home to Colorado, you heard that Bjorn-Eivind had died while ice climbing in his native Norway. Among the many alpinists you’ve met over the years, you’d felt particularly close to him, seeing in his life, I think, a model for your own. Kind and gentle, and yet brimming with spirit, striding off long-legged into the vast, radiant wildness of Patagonia, he may have given you a glimpse of how you, and how climbing, might fit into a bigger, more complicated world.

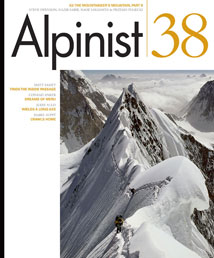

![hayden-kennedy-2 Hayden Kennedy. [Photo] Urban Novak](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hayden-kennedy-2.jpg)

This Sharp End first appeared in Alpinist 38–Spring 2012.