What happens to the solitary creativity of our pursuit as more climbers perform for a mass audience? Mountaineering historian Andy Selters investigates what may become one of the defining questions of our era.

CLIMBING EMBEDS IN US A LOT OF DISTINCT RHYTHMS: the strains and rests along the hard and easy parts of a route; the ebb and flow of swinging leads; the sky-rhythms of day and night, and calm and storm; and of course, the overall cycles of going up and coming down.

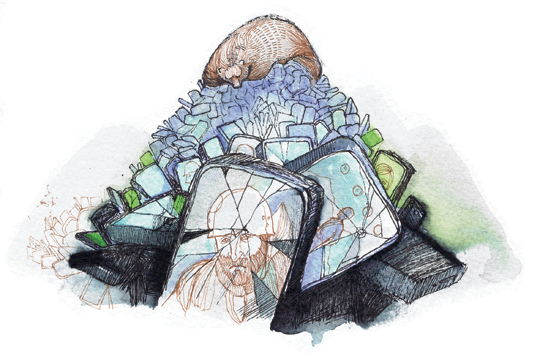

These rhythms rise out of the meetings between terrain and our imagination to climb it, and they connect us to that terrain in the same way that music connects us to culture. We could think of ourselves as improv musicians, playing the up-beats of our being into the rhythms of rock, ice and snow. Some of us climb like jazz artists, others more like marching soldiers; some are like heavy metal headbangers, a few are virtuosos like Clapton. Whatever genre and style, terrain has songs that resonate in climbers in a way that’s rare and vital in the modern world.

Surrounding all these rhythms is the cycle of taking leave and returning home. We venture off from work, strife, security and friends, we go do our up and down, and we come back changed. This Homeric journey has practically defined the soul of alpinism, especially for North Americans. Now, though, is that path of going apart and coming back dissipating into the always-connected?

I had to ask this question when I read the now-famous article in The New York Times, “On Ledge and Online.” The piece featured Tommy Caldwell updating his Facebook status by iPhone from the middle of his Dawn Wall project. In many ways, this story wasn’t news at all, as climbers have long been connecting by phone, wireless or mail runner. Yet today’s hyper-connectivity seems to merge the once-separate acts of sending a route and sending the news of it into a continuous thread. Sarcastic old-timers are rephrasing the ancient question about falling trees: If a climb gets done and nobody hears about it, did it really happen? Are visibility and live feed going to become the measures of a climb’s success? Caldwell was quoted, “This is a whole new world.” Maybe. At the least, it’s time to re-ask: Are we seekers going apart, or athletes for an audience?

Beware. Audience is a powerful force that draws performers into the entertainment it craves. I played high school football in Southern California. The running, tackling, blocking and teaming with friends had the physical intensity and partnership of climbing, but the heart of the game was to compete for attention in battle. Donning armor and school colors, we were groomed for violence. When I stepped away from the collective roar, football players seemed like absurd gladiators colliding by arbitrary rules in a rectangle.

Fortunately, I discovered I didn’t get along with stadiums, smog or much else in Southern California, and I sought mountains, places apart. I went off to college in far Northern California, joined some other renegades, and started exploring the Trinity Alps, the Siskiyous and Mt. Shasta. We inhaled the smells of forests, drank stream water, and (especially when we climbed) felt as if we were engaging a wondrous universe outside the castle walls. There were no guidebooks, no known routes, no one to listen to our tales. We just followed the maps and our noses, and we ferreted out a lot of nice crags and ice that probably nobody cares about still today. Climbing seemed to transform me into a free, conscious, and competent person, playing out intrinsic passions in beautiful landscapes, disciplined by natural law.

But the mainstream roar is powerful, and in my head, the world I came from still echoed in anti-rhetoric: This is so cool, it’s so far away from LA. Then I’d get gripped on a crack or an ice pillar, and I’d realize that my progress and ultimately my survival depended not on being apart from LA, but on rooting my toe onto individual crystals of granite, or sinking a tool into a drip of ice. I’d reflexively look around for encouragement or rescue, and of course there’d be no one but my partner, no sounds but perhaps the wind and my own whimpering. Shut up and climb was the only hope, and so wilderness climbing distilled me into an unadorned athlete without an audience.

I’d wandered into an extreme, backwater version of the twentieth century’s non-conversation between climbers and the public. Climbers would come back filled past the brim with amazing journeys, and the best that the mainstream could greet us with was, Why? In the ’60s and ’70s, there was an unspoken, anti-response to that dismissive question. It was something like, Because, you dumbasses, the mountains are a magnificent and intact world; maybe you just have no imagination for what it’s like to venture outside of your cubicles, freeways, hair cream commercials, wars and other witless aggression.

Today, climbing collects applause, lots of it. The suits appraise how climber branding can increase sales, the climbers compete for the moral and financial support that escalates the climbing life, and the public adds us into its entertainment mix. As banners of climber-celebrities drape from skyscrapers, as sponsors and grants support new levels of full-time climbing, social media seems to be buzzing louder than the personal drive to climb. Is there space in our skulls for all this?

Inside any of us there are two voices: a shared, public voice and a focused, private one. They both collaborate and compete for airtime. The public voice connects us, helps motivate and inform us, and it influences a lot of our imagination. But it also distracts us from the ultra-awareness we need to carry out transformative acts. For most people, most of the time, the public voice keeps us moving and in line, and we go around doing things that reinforce and extend our social and economic connections, without really asking whether they’re right for us. If it’s sanctioned, if it gets us fed and ahead, it’s what we do. But our instincts and history, I believe, tell us that the best–and safest–climbing happens when we disconnect from the public voice, take original and full responsibility, and immerse our whole mind and body into the rhythm of a route. Whether the public voice we hear calls out doubt or encouragement, when it comes time to climb, it’s all noise, added stress that limits our potential and pulls us dangerously offbeat. When we listen to and move by the rhythms of terrain, that’s when climbing rocks.

Who can say if a climber is more connected to audience or terrain? No one. But the expansion of audience is becoming like a gravitational mass, shifting our balance, pulling us toward what the crowd can recognize and measure–accomplishments such as speed, rated difficulty and 8000-meter peaks. Throughout history, however, it’s usually been the climbers who can disconnect from the buzz who hear the rhythms of terrain more clearly, and who uncover new levels of endeavor.

IN THE MID-1960S, ALPINISTS LOOKED TO ALASKA and saw a lot of big mountains being climbed by big, toiling, siege expeditions. A few young Davids started asking whether they could bring fewer resources and more temerity at least to some medium-sized Goliaths. Don Jensen was at the core of those ready to risk paring down team size. He was a Harvard math student with a visceral need to engage the mountains. He hated the snob-culture of his university. Massachusetts in general drove him nuts because the dense overcasts, flat forests and urban mazes prevented him from orienting to north. In 1964 he and co-sophomore David Roberts launched one of the first known two-man expeditions to a big Alaskan peak, Mt. Deborah. They took in Alaska’s travails–the weeks of storms, the isolation, the desperate climbing–with only a tiny tent and each other to count on.

The next year, they came back with two other buddies to complete one of Alaska’s first really technical routes, on the west face of Mt. Huntington. To streamline their effort, Jensen designed the next generation of gear, including the first contoured “soft pack,” the first really effective bivouac tent (“The Bombshelter”) and “icelites,” barbed picket-pitons that were “godsend” anchors in Alaskan snow-ice. Jensen never addressed an audience with an article. But within the history of Alaskan mountaineering, I think we can trace much of the impetus for going light and eventually for alpine style to Jensen and Roberts’ adventures.

A decade later, campfires buzzed with a rumor that few could believe: some guy had soloed the Cassin Ridge on Denali in one and a half days. Charlie Porter is the ultimate “silent” climber, known for disregarding even the public record. Yet he’d already pioneered six of the most spectacular routes on El Capitan, plus the Canadian Rockies’ Polar Circus. He’d also made the first ascent of the northwest face of Mt. Asgard on Baffin Island–what many call the world’s first Grade VII–alone. After the Cassin, he carried on to the first ascent of Middle Triple Peak, with Russell McLean. Porter probably never even sent an unsolicited note to the American Alpine Journal. He kept his focus on the next big questions, envisioning realms of potential that people busy comparing themselves to others couldn’t imagine. In a different way, he’s still at it now, sailing and climbing with scientists in southernmost South America, helping them unearth answers in archaeology and climate change.

Although Porter maintained his purity by keeping his stories to himself, public storytelling doesn’t have to mean dancing to the public’s tune. For Peter Croft, honesty in reporting is part of engaging terrain with integrity. Climbing hard is valuable, but not because it makes you famous: “When you’re at your limit, there’s no room for other voices, it has to be just you focused on the rock…. When you’re on your second El Cap route of the day and you’re getting exhausted, you have to forget about the significance of the thing, and find an extreme psyche…dig deeper than you thought you had. I think that’s really good for us.”

Croft doesn’t climb to impress an audience. A few years ago, he told me that traversing super-long crests in the Sierra had brought him to “a level beyond Yosemite.” He said, “My Yosemite friends won’t understand, but I’ve had the best season of my life, and I’ve never made a move over 5.9.”

As he became famous and sponsored, Croft brought his level-headed honesty along. “We all have egos, we like to see ourselves in print…. Anybody who tells you that they don’t care what the world thinks of them is basically in denial….

“Marketers and media today definitely direct events and steer what climbers go for. It’s business negotiations; how much focus and time do you put into [connecting with sponsors and the public] versus how much money do you get and how much compromise of your climbing goals.”

When Croft feels his spirit lining up with a route that matters to him, he doesn’t allow any distractions. “When John [Bachar] and I teamed up for El Cap and Half Dome, it was like the whole world came together for us. There’s no way I would have taken any amount of money to have film crews or whatever with ropes strung up there.”

For the late John Bachar, public display and private focus blazed at both poles. Many of us probably recall his days as the phenomenal soloist with the shocking swagger. But Paola Accusani, the soulmate Bachar found in his last few years, as well as his close friends Croft and Bruce Lella, are among the many who speak mostly about his private, deep connection to stone.

Accusani says, “He had a huge ego. But he used ego as a vehicle, to get to the other side…. He studied martial arts, especially the mental concentration…. Climbing for him was a way to strip away the exterior and get him to the essence of life, death, and the great mystery that we all inhabit.

“John always said that his best soloing was when no one else was around. He calculated that he’d soloed nearly 3 million feet of rock. That’s days, weeks, and months, alone with the rock….

“John fought demons. He said that the best thing to quiet the noise in his mind was free-soloing.”

This points to maybe the simplest explanation for climbing: the mind engages challenging terrain, seeking a path for its own purification.

Among Bachar’s unfinished legacies is a booklet of koan-like aphorisms that climbing inspired into him, thoughts he wanted to pass on to his son, Tyrus. One of them reads:

Sometimes you have to close your eyes so you can see.

Within every rock exists a climb.

TODAY THE PUBLIC VOICE ENCOURAGES US to “go for it”: climb hard, and you will be rewarded. Such booster noise is far more insidious than the old Why? that promised nothing. I make this statement knowing that if anyone had offered me and my partners sponsorship or recognition for our climbs in the Trinity Alps, we all would have asked how high we needed to jump for it. But while a crowd’s roar works for athletes playing in a stadium, alpinism is a risky life-venture into serious uncertainty, and bringing the rhythms of terrain, body and mind together is crucial. What plays in our minds really matters, and when media worms its way in, it usually inflates us to expect that success against odds is the norm. Beware: the roar of applause can sound a lot like the intensity of accurately negotiating the razor’s edge. In severe climbs, how many of us can really parse the difference? Alpinism has an appalling death toll, to make football violence seem like child’s play, and we have to ask, how much are we pulled upward by the magnet of social escalation, even when the terrain is telling us, Not here, not now?

The emerging global village, where everything anybody does matters to everyone else, is both our brilliant new world and our modern nightmare. It has been said that “celebrities rent space in our brains.” Today, we can all vie for rental space in everyone else’s brains. Networking is energizing, easy, fruitful and educational, but it can easily distract us from the ground we walk, the holds we grasp. The alpinists who thrive in this modern paradox are those who know themselves clearly, who can connect well both to terrain and to the public imagination, and who know the difference. Reinhold Messner is the master at reading whether or not there’s passage through the evanescent gauntlets above 8000 meters, then jumping back to his rostrum to lecture us into accepting his definition of alpinism.

Tommy Caldwell is comfortable these days balancing his climbing and his role as a public figure. “Ninety-five percent of my climbing is private, just me and a partner, and I never want to give that up,” he explained to me. As fanfare started to collect around his Dawn Wall project, he first called it “the circus,” but when he decided to join it and post (twenty-five updates during last autumn’s stint), he said, “I became a believer.” After a day of climbing, he’d spend just a few minutes texting from the ledge. He figured that’s a pretty good ratio, and he came to enjoy inspiring people at their desks and pizzas. He acknowledged that his sponsors always want more. “Money equals pressure, no matter what you do.”

Of course, Caldwell was on a well-resourced siege of El Cap. Climbers immersed in more severe commitments have not found on-route connecting so tasty. Even still, it’s interesting to recall the hoopla of mystified Whys? that surrounded Warren Harding and Dean Caldwell when they aided the first ascent of the Dawn Wall in 1970. Today, nobody asks Tommy why. When a big audience underwrites an endeavor, soul-searching apparently is no longer necessary. A modern climber need only speak to the public with “fresh, in-the-moment” clips that resemble NFL wrap-up jargon. In this instagram world, climbing literature that probes the depths of experience, like that of David Roberts, is often cast aside.

To find the essence of a route, it’s helpful, and probably essential, to turn your head away from its social value. In 1963 Tom Hornbein and Willi Unsoeld had joined one of the highest profile expeditions in American history. With $400,000 in sponsorship from television and National Geographic to satisfy, their leader had to prioritize a secure siege of Everest via the South Col–the “First American on top” tale that would play in Peoria. Hornbein and Unsoeld’s imaginations, however, were sparked by the unclimbed west ridge and by the idea of traversing the peak–a pie-in-the-sky to mountaineers, and a half-cocked-over adventure to everyone else. They progressively disconnected from the South Col thrust, and patiently explored the possibilities of executing their own vision. They scouted the route, ferried up supplies and waited for scant leftovers of support and better weather.

They also disconnected from the hope for recognition. With time on the mountain, Hornbein explained, “Everest came down off Everest. It became, in a climbing sense, just another mountain to be approached and attempted within the context of our past experience in the Rockies, the Tetons, or on Mt. Rainier. Not quite really. But much of the battle lay inside. [By the time their chance to climb the West Ridge came] that battle was nearly won” (Everest: The West Ridge, 1998).

This is the model for negotiating through the dueling forces in our head: ego might fire us to take on a challenge, but it’s humility that gives us the clarity not only to see if and when a route is right for us, but also to break through our perceived limitations. Hornbein and Unsoeld’s ascent of the West Ridge will forever be among the most impressive American ascents of anything, and they succeeded because they turned off the notion of Everest as the ultimate accomplishment and focused instead on finding passage through the stack of rock and snow that happens to be the highest mountain on earth.

Hornbein arrived at this: “Existence on a mountain is simple. Seldom in life does it come any simpler: survival, plus the striving toward a summit…. It is this simplicity that strips the veneer off civilization and makes that which is meaningful easier to come by.”

People like Croft, Hornbein and Caldwell attained their public stature by simply climbing, and leaving the telling of their stories to later. Be wary of compounding the simplicity of your own climbing with hopes to sit at that table. Technology and a readily twittered public seem to make it easy to mix networking and climbing, but the difference between connecting to terrain and to an audience has profound consequences. I think that this idea is what Marko Prezelj was getting at when he rejected the 2007 Piolet d’Or: “I don’t believe in awards for alpinism.” He practically spit at what he called, “an arena where spectators thrive on drama, where winner and loser are judged.”

So are we seekers, or athletes? It’s up to us; mountains are open to our interpretations.

But it’s hard, even risking a fool’s errand, to try to be both at the same time. Maybe we’d do better to think of ourselves as musicians. Radical terrain rings with special music, and going off to jam with it is a gift and a discipline. Whether it’s Mick Jagger or a local Bishop bass player, musicians get energy and income by engaging audiences. But when it’s time to compose a new work, or do justice to any great song, a good musician knows how to tune out the crowd and find the rhythm that inspires.

[Enjoy this article? Read the rest of the issue by downloading it from our app or buying the back issue.–Ed.]