The Cahuelmo anchored in an estuary below Cerro Corcovado, Chilean Patagonia. [Photo] Scott Soens

In 1968, Yvon Chouinard, Dick Dorworth, Lito Tejada-Flores and Doug Tompkins drove a Ford Econoline van from Ventura, California to Chilean Patagonia. The trip made not only a profound impact on the lives of these four climbers and surfers, it also forever changed the landscape of the outdoor industry–and the destination itself. Chouinard went on to found the clothing company Patagonia and Chouinard Equipment, which would become Black Diamond Equipment; Tompkins went on to found clothing company The North Face and, later, one of the world’s largest privately owned public parks. Parque Pumalin in northern Chilean Patagonia contains about 800,000 contiguous acres and is just one of Tompkins’ many land-conservation projects in the effort called Conservacion Patagonica.

Four decades later, their trip still resonates. In the late 1990s, photographer and Patagonia employee Amy Kumler chanced upon an old VHS film in the Patagonia vault. The film, Mountain of Storms, documented the 1968 journey from Ventura to Fitz Roy, and Kumler thought a certain surfer friend, Jeff Johnson, should watch it. When Johnson and Chris Malloy sat down to view this never-distributed reel, they were so moved that they planned a climbing and surfing excursion of their own. They hoped, as Fitz Roy had for Chouinard 30 years earlier, that the trip would shape their futures.

The result was a formative trip to Australia, climbing at Mt. Arapiles and washing off the salt on surf breaks. Johnson and Malloy did not produce a film, however, and instead searched for a deeper story to tell. That story is 180 South.

Eventually, Johnson and Malloy decided to find their own way to Patagonia. They began with an ascent of the North America Wall (VI 5.8 A3) on El Capitan, first climbed by Chouinard, Tom Frost, Chuck Pratt and Royal Robbins in 1964. (Keith Malloy and Timmy O’Neill, high on that wall, grace the Table of Contents page in Alpinist 30. Subscribe to Alpinist.) They then sailed from Ixtapa, Mexico, to Rapa Nui (Easter Island) and Chile, exploring its peaks and waves with Chouinard, Tompkins and O’Neill.

Alpinist interviewed Johnson and Malloy about the project. Their perspectives on the liberation of adventure–and how it can do good in the world–are below. Get the full story of their travels by checking out 180 South: now a DVD and large-format book with more than a hundred photos. Learn more about the trip and view video trailers at 180south.com.

Keith Malloy and Timmy O’Neill bivy in the Black Cave, North America Wall, El Capitan, Yosemite, California. This photo is the backdrop for Alpinist 30’s Table of Contents. [Photo] Jeff Johnson

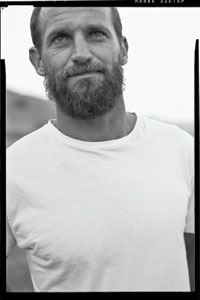

Jeff Johnson, Valle Chacabuco, Chile [Photo] Scott Soens

An Interview with Jeff Johnson

In the film 180 South, Yvon Chouinard says that true adventure begins as soon as everything goes wrong. What is your definition of adventure?

I agree with Yvon. When the mast broke while sailing to Rapa Nui, it really felt like the trip had just begun–even though we were two months in. Suddenly our future was up for grabs, nothing was certain and all plans were off. True adventure forces you out of your comfort zone, and that’s when things get exciting.

When you watched Mountain of Storms, what about your worldview changed?

I don’t think your worldview ever changes quickly–it happens over time with the accumulation of experiences. Mountain of Storms inspired us through the raw adventure we saw, all the things they did along the way. Basically, we thought it looked fun and wanted to do something similar one day. It wasn’t until I was on my own journey, 40 years after theirs, that my perspective on adventure began to shift. That’s when I finally understood what we had seen in that film from 1968.

Originally, Mountain of Storms inspired you to shoot footage of a climbing and surfing trip of your own, in Australia. What did you learn from this project, and how did it later influence 180 South?

I had only been climbing a little while at that time. I started kind of late, in my early 30s. And Chris hadn’t been climbing much–just a little bouldering and a few climbs here and there. I don’t think we really knew what we actually wanted to do. We were winging it, crossing back and fourth between the coast and Mt. Arapiles, getting spanked on climbs and washing it all off in the ocean.

Chris had made a few successful surfing films by then. But to make a film, he needed more than just cool footage. He needed a story that had to be told. Five or so years later, we found some of the right ingredients for what he wanted, and the result was 180 South.

Keith Malloy finds solitude north of Puerto Montt, Chile. [Photo] Devon Howard

For you, what connects climbing and surfing?

One thing that climbing and surfing have in common is style. But in surfing, style is more about looks–it’s a little vain–whereas in climbing, style is connected with ethics. Climbers don’t care how they look, but how they act. Surfing is the opposite. To me, this is what makes climbing so unique and honest; it’s why I’m so attracted to it. I hope it remains this way.

In 180 South, your biggest goal was to climb Cerro Corcovado, but rotten rock caused you to turn back a few hundred feet from the summit. What did you learn from this experience? Will you go back?

Jeff Johnson finds a rare chunk of consolidated lava to climb. Mataveri, Rapa Nui (Easter Island). [Photo] Tyler Emmett

I learned to plan better. Ha! Well, I would have been there with better snow conditions if the mast didn’t break and we didn’t have to spend a month on Rapa Nui. The broken mast might have shut us down on Corcovado, but it also gave me some priceless experiences on the island.

Honestly, I’m not sure what I leaned from that. I guess it has something to do with advice Ron Kauk once gave me over the phone, when I was heading to the Valley. I told him I’d make plans when I got there. He said, after a long pause, “Best not to have any plans, bro.” So true.

I’ve talked about going back to Corcovado in the thick of winter, when it would be more climbable. I think about that often. It may never happen. But I do know that I wouldn’t go back without a surfboard. The thing about Corcovado is what’s around it. To go there just to climb would be a waste. There’s so much beauty that surrounds it–you gotta dive into all of it.

Dave McGuire checks the rigging aboard the Seabear halfway between Isla de Coco and the Galapagos Islands. [Photo] Jeff Johnson

The film and book suggest that simplifying is not just a healthy individual choice but also a healthy community choice. Why reach out to climbers and surfers with this message?

It’s climbers and surfers we know the best–the communities we are most connected with. A big part of climbing and surfing is travel. We have an impact on these places we visit. And, because we all travel so much, we are sensitive to the world being connected, that everything we do affects someone else. Simplifying is easy to understand. Rather than a sacrifice, it adds to your life, makes life better, I believe.

180 South gathered like-minded adventurers for many months, and the book and film culminate with the first ascent of Cerro Geezer in Valle Chacabuco, Chile. Then the group disbanded. Did this final time together serve as a logical end or beginning?

Well, it’s how it happened. Yvon and Doug were planning on climbing Cerro Geezer–they had tried it a year before. Having me along wasn’t planned. Everyone else was leaving, and we thought the thing was over. Then, out of the blue, they invited me to come along. Because it was planned so last-minute, Chris didn’t have this climb in mind, especially for the end of the film. But it worked.

There were so many times during the filming that were almost too perfect, and we’d look at each other in awe. Like dolphins and seals jumping up as soon as Keith and I went for a paddle, or the snow storm that hit us on El Capitan. It was like being in Universal Studios where someone on a megaphone was yelling, “Cue the dolphins! Cue the snow!” Cerro Geezer was one of those.

Where are you living now, and what are your future travel plans?

I live in Ventura, California right now. As far as travel, I’m listening to Ron Kauk’s mantra: “Best not to have any plans, bro.”

Doug Tompkins and Yvon Chouinard near the top of the upper glacier on the first ascent of Cerro Geezer, Chilean Patagonia. [Photo] Jeff Johnson

An Interview with Chris Malloy

What was your artistic vision for 180 South?

My aesthetic has always been informed by the mid- to late-1960s work of people like Fred Padula, Leto Tejata-Florez, John Severson and Albert Falzon. Most of them worked with a Bolex 16mm film camera. These guys were part of the adventures they documented–they had a different perspective than outside film crews, foreign to the places and experiences, would. These artists were so immersed in the experience itself that they could create a language that authentically spoke to other climbers and surfers. This shows in the small nuances that they took time to film, and that’s what I’ve always looked for in my own work.

Mountain of Storms had a profound impact on your perspective on adventure. Did it also have an impact on your life trajectory?

Jeff Johnson and I had found a kindred spirit between climbing and surfing. Without any concrete reason, we spent months researching places in time where they had crossed paths. When we found Mountain of Storms it brought everything together. It was at that time we started talking about doing a trip loosely based on their route.

Timmy O’Neill and Keith Malloy two pitches from the summit on North America Wall. [Photo] Jeff Johnson

What was the most challenging part of filming this project?

Having money. I’ve always shot super stripped-down films, and couch surfing with a couple cameramen has been the norm. In the past, I always used 1970s-era Bolex cameras because you don’t have to charge batteries. And if they break, you can usually fix them with a screwdriver. For 180 South, we shot HD, and we had budgets and schedules and a production team. That was odd for me. It was compromising.

What was most rewarding about being involved in 180 South?

The film is bringing light to what is happening in Chile. Dams are destroying the cultural and environmental resources, and coastal factories, like cellulose mills, are polluting the sea, air and land. Bringing that message to folks is important. Most climbing and surfing films go to far flung regions of the world, document the good, leave out the bad, paint a pretty picture and call it good. 180 South takes a different approach, one that might effect change, and that’s rewarding.

Timmy O’Neill near high camp on Cerro Corcovado, Chile. [Photo] Jeff Johnson