Below is one of four essays found in the 30-page Mountain Profile on Zion National Park, by Ethan Newman, from Alpinist 53. In this essay, set between 1998 and 1999, contributor Cameron M. Burns recalls a new route he tried between bouts of heavy rain with Fred Beckey and Pete Doorish in 1998, but ultimately finished with James Garrett and Chris Eng (a year later) on Zion’s Red Arch Mountain. Burns also mentions another, even longer route he and Warren Hollinger established on Zion’s Mountain of the Sun.

[Photo] Cameron M. Burns

COFFEE LIFTS ON THE AIR. A dog marks time (and place) in the distance, its tail a silent metronome. The cold air, gently sinking, pulls a breeze across my face. I don’t like it. I want to crawl deeper in my bag. From the floor of the living room in John “Deucey” Midddendorf’s Hurricane home, I can just see the top of Mt. Kinesava, I think, starting to light up in the eastern sun. The southern tip of Zion–and its wide canvases of stone–seems ready to swallow me in ideas, dreams, wonder and fear.

It’s the rock that brings the fear. Zion is made up of Navajo sandstone in generally two discrete layers. One, a lower red layer–the first thousand feet or so–gets its color from iron oxides; and two, a more pinkish, yellowy band sits atop the red stuff. Millions of years ago the upper layer included considerable hematite, which dissolved, leaving the rock friable and porous.

I prefer the granite of the Valley; it’s not a question mark. Even the red Entrada around Moab feels more secure; it’s not a weak, sickly color that reminds me of my own body.

Years before I ended up here, in April 1998, on the floor of this Hurricane house with Fred Beckey and Pete Doorish–Deucey told me that commitment on the walls of Zion could be rattling, at the very least.

————————————————————————

IN 1993 DEUCEY AND I hiked Arches’ Fiery Furnace with the late desert pioneer Eric Bjornstad and my future wife Ann. Something Deucey muttered caught my attention.

“A thousand what feels like what?” I asked.

[Photo] Pete Doorish/Cam Burns collection

“A thousand feet of sandstone feels like 2,000 feet of granite,” Deucey repeated. “That’s sort of how I look at Zion. The commitment on those walls is just so in your face. Especially up high where it gets more porous.”

He was right, of course. I’d learn so in 1996, when Warren Hollinger and I climbed a new grade VI route on Mountain of the Sun. After the first 1,000 feet, you can snap pieces of stone off with your fingers like honeycomb toffee. The texture reminded me of Violet Crumble, a confection I grew up with in Australia.

This time, Fred, Pete, and I are sticking to the first 1,000 feet. The red stuff. The good stuff.

IT’S RAINED FOR SIX DAYS and nights straight. Pete, Fred and I fixed a pitch of our new route when the storm started and we retreated to Deucey’s house. Deucey wasn’t there, so we had to break in. The place is seemingly abandoned. If memory serves, he’s off studying design at Harvard. We camp on the floor like hobos, the rain constantly drumming. Our positions in sleeping bags seem as set as fossils in the geologic catalogue of time.

Fred always looks at home in a bag. His face reminds me more of the Zion stone than that of other areas–except instead of gentle waves, Fred has chiseled cracks, lines he’s earned.

Huge cracks also burst through the drywall of Deucey’s house, across whole sections of every room. I feel as if I’m in a diorama of the Grand Canyon. Fissures everywhere. Deucey always had more motivation than most, I recall; his climbs settled into Zion lore like the dust that settles here.

Fred wakes up before anyone else and walks down to the nearby 7-Eleven and buys a copy of the Wall Street Journal. Then–back in his sleeping bag, of course–he reads the stock quotes, calls his broker and gets to trading.

Fred’s life is something of a contradiction.

After a full week spent prostrate around Deucey’s home, we quit Zion, empty-handed. Four pitches in eight days–an abysmal achievement.

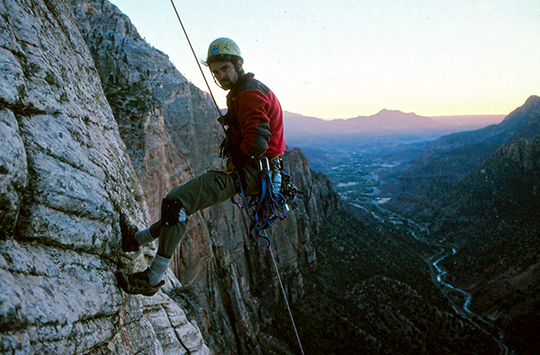

[Photo] Cam Burns

NEXT MARCH, I RETURN with James Garrett and Chris Eng. We head straight out to the abandoned project. The weather holds, and we labor up Zion’s red drapery, enjoying the quality of the stone and the crack systems that seem to unfold before us the way a highway rolls out before a sports car.

In a single day, we’ve crested Pitch 6 and are gazing at ripples. Deep red stone that someone’s skipped a rock across. Ripples and more ripples. Tiny disturbances on the ocean’s surface. I miss Fred and Pete.

We retreat to the Watchman Campground for a quiet dinner. The pink and orange evening light soothes our stress. Our weariness helps us relax. The tall cottonwood trees stand as dark sentinels around the campground.

IT’S 4:45 A.M. I’M BETWEEN dream and consciousness–a weird area I hate–both ends pulling me their way. I’ve never been able to sleep soundly the night before jumaring, a one-point-of contact activity, but I’ve never been able to stay fully awake either. For me, bivouacs under these circumstances have always been a sort of wall climbers’ purgatory. Worry battling fatigue.

In the morning, past the highpoint, I start off on a long corner, reaching a roof just as the rope pulls tight. James comes up, and then storms past me, wiggling himself into a slot before disappearing, cursing heavily. Then Chris arrives with the bag.

(Why we have a haulbag on such a short route is beyond recall now, but I remember Chris’s gaze when I asked him take it to the top of the next pitch. He could’ve shattered porcelain with that look.)

We top out after dark and prepare for a night on the stone, which by this point has turned black and cold. Big jackets come out, we sit, and the hours drip by. You can almost see the stars twirl around the heavens.

In the morning we rappel off, tired, worn, but satisfied. We treat ourselves to a restaurant meal that evening and crash on fat bellies. Another Zion wall ticked, another adventure ingrained in the senses. Another commitment met, signed, and delivered, another crack in the memory.

Cameron M. Burns is an author, artist, ski instructor and soccer dad. He spent 16 years working on green building and sustainability issues. He’s authored or co-authored 11 books, including Postcards from the Trailer Park: The Secret Lives of Climbers and Selected Climbs in the Desert Southwest: Colorado and Utah.