[A] (Not shown.) Everest summit (8848m). [B] Lhotse (8516m). [C] Nuptse (7864m). [D] South Col (7906m). [E] Geneva Spur. [F] Lhotse Face. [G] Western Cwm. [H] Khumbu Icefall. [I] 2013 Camp I (6100m). [J] 2013 Camp II (6500m). [K] Location of argument with fixing team (7100m). [L] 2013 Camp III (ca. 7500m). [M] 2013 Camp IV (7906m). CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE. [Photo] Dick and Pip Smith/Hedgehoghouse.com

From Base Camp on the Khumbu Glacier, on the south side of Mt. Everest (8848m), clients, Sherpas and guides shuffle through the meticulously prepared Khumbu Icefall that, from a distance, seems to consist of more air than solid ground. Spreading up from Camp I at 6100 meters, the Western Cwm forms a comparatively gentle incline, crowned by Everest, Lhotse and Nuptse. At the head of the valley, the Lhotse Face rises from Camp II around 6500 meters at an abrupt forty- to fifty-degree angle, oscillating to form steeper bulges and small platforms amid a cascade of crumpled ice. It’s the first continuously steep section that clients encounter on their mass migration to the summits of Everest or Lhotse. But before that march begins, Sherpas prepare the route by fixing lines up the 1400-meter face.

In late April, western guides and sirdars met in low on the mountain to decide how many and which Sherpa climbers would fix the route up the Lhotse Face. “It’s usually the key operators that will kick in with Sherpa power but they also try to get some of the private teams to help out,” wrote Becky Rippel, who blogs about her husband Tim’s work as a guide at Peak Freaks. “There’s quite a bit of politics and planning that go behind the scenes for the fixing of rope up the route from Camp II to the summit.”

As usual, there were several absences from this year’s meetings, including the team leader of the noncommercial expedition NO(2) Limits: Simone Moro. Moro, who said later he was not aware of the meetings, planned to do a light-style linkup of the Hornbein Couloir on Everest and a new route on Lhotse without supplemental oxygen or fixed ropes with Ueli Steck and Jonathan Griffith.

By the end of a meeting on April 25, the guides and sirdars had chosen the members of the fixing team, set completion dates and agreed that no one would climb on the Lhotse Face until the work was finished, a usual arrangement for commercial teams on the busy normal routes of 8000-meter peaks. “On Everest and anywhere in the Himalaya it is an unwritten rule that climbers will have to wait until the route is opened by the Sherpas,” high-altitude worker Norbu Sherpa said to The New York Times.

“Going to Everest is a different game [from climbing less-crowded mountains],” Steck told the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation after summiting Everest for the first time in May 2012. “It is not real mountaineering, but I have to accept the rules. I often had to wait behind the rope-fixers, but I would not pass them out of respect for their work. I often did not clip onto the fixed ropes.” Moro, on the other hand, later explained to National Geographic, “I’ve climbed Everest four times and done ten expeditions here, and I know that on the day the ropes are fixed, nobody should hang on the fixed ropes. This doesn’t mean that nobody is allowed to climb the mountain. Everest isn’t just a mountain for clients and guides. Everest is for all who pay the permit.”

THE NORMAL ROUTE ON THE SOUTH SIDE of Everest roughly follows the line taken by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay on their successful first ascent in 1953. The route meanders up the fractured center of the Lhotse Face to gain the South Col (7906m). The remaining 942 meters trace the Southeast Ridge to the summit. Co-owner of Benegas Brothers Expeditions Guillermo “Willie” Benegas–who has attempted the North Ridge of Latok I and established a new route on the north face of Nuptse with his brother Damian–began guiding annual trips to Everest almost fifteen years ago. Soon after, he recalls, the route commonly fixed for commercial teams started to evolve from the original route, which risks protracted exposure to falling ice, to a more-direct variation that took much less time to prepare but was subject to increasingly frequent rockfall.

At the same time, less snow remained on Everest through the climbing season. A study published this spring by Nepali scientist Sudeep Thakuri of the University of Milan shows a 13-percent glacial shrinkage on and around Everest since the 1960s. The snowline is also 180 meters higher than it was 50 years ago.

“There’s been a drought for last ten years, and it’s getting drier and drier. And we had to acclimate to those changes–by changing the route, changing the way we set up the anchors–several years ago,” Benegas explained. Commercial teams made a controversial decision to retro-bolt parts of the 1953 route, adding six bolts on the Yellow Band in 2009 and ten to twelve more above the Triangle Face last year to replace what used to be ice anchors. “It’s all dirt,” Benegas says. “We have to take responsibility, we have to make it safe otherwise were going to see 200 deaths in one shot.”

tag: seamless=”seamless” scrolling=”no” frameborder=”0″ allowtransparency=”true” allowfullscreen=”true”

[A] (Not shown.) Everest summit (8848m). [B] Lhotse (8516m). [C] Nuptse (7864m). [D] South Col (7906m). [E] Geneva Spur. [F] Lhotse Face. [G] Western Cwm. [H] Khumbu Icefall. [I] 2013 Camp I (6100m). [J] 2013 Camp II (6500m). [K] Location of argument with fixing team (7100m). [L] 2013 Camp III (ca. 7500m). [M] 2013 Camp IV (7906m). CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE. [Photo] Dick and Pip Smith/Hedgehoghouse.com

In late April 2012, continuous rockfall injured six people as they jugged the fixed ropes up the direct variation on the Lhotse Face. American climber Chad Kellogg was nearly killed by a large rock falling from high on Lhotse. Dr. Ashish Lohani of the Himalayan Rescue Association (HRA; aka Everest ER) reported two broken arms, two hand injuries and a laceration from rockfall to Outside Magazine. Lakpa Nuru Sherpa sustained severe brain, jaw and eye injuries. Initially, his employers at Summit Climb hesitated to pay for the $15,000 helicopter rescue, Senior Editor Grayson Schaffer reported for Outside. Eventually, the company paid $11,000 of the total for the uninsured part of the rescue. Simone Moro piloted the helicopter evacuation. Soon afterward, teams switched to the more-circuitous route, though the day after it was fixed, some Sherpas continued to use the direct line.

IN LIGHT OF THE PREVIOUS YEAR’S HAZARDOUS WARMING CONDITIONS, attendees of the 2013 fixing meeting in Camp I decided, after a lengthy discussion, that the team should try the circuitous 1953 line, with the direct line as Plan B. “We were not sure if we could get through the crevasses, but that we should at least look at this route first,” says Russell Brice, owner and operator of HimEx. Ultimately, the climbers selected for the fixing team included three foreigners: Damian Benegas, Chad Kellogg and Rory Stark.

“It is an honor as a Westerner to be in front with the Sherpa rope-fixing. And it is good for our reputations,” Alpenglow Expeditions owner and guide Adrian Ballinger said. “[Select Westerners have] been asked to assist in fixing in past years, especially when there is potentially difficult decision-making or complicated anchor replacement or bolting.”

But, normally, Sherpas now make the fixing decisions, says Marty Schmidt of Peak Freaks, who has been guiding for thirty-eight years. “There is an understanding with the Sherpas and Western teams in the past that the Sherpas will [choose the fixing route], with the Westerners being involved with the organizing, getting the rope and gear, setting up the loads to be carried, etc.”

An Ever-shifting Balance

WHILE THE MODERN FIXING TEAMS–often the most experienced and best-trained Sherpa climbers on Everest in a given season–have achieved some respect within the commercial guiding community, their status is the result of many years of evolving power structures in Himalayan mountaineering. Today, the word Sherpa is often used to refer to high-altitude mountain workers, but it also designates an ethnic group of eastern Tibetans who settled in the Solu Khumbu Valley hundreds of years ago, in a region that is now a district of modern Nepal. During the early twentieth century, the Scottish mountaineer Alexander Kellas began hiring Sherpas for his Himalayan explorations. His praise of their ability to climb at high elevations influenced other early British expedition leaders who employed them to assist climbers with the initial reconnaissance and attempts on Everest.

“In the 1920s, the partnerships between Sherpas and Westerners were relatively new,” Peter Athans, who has participated in fifteen Everest expeditions and who serves as program director for the Khumbu Climbing Center (KCC), explained to Alpinist Editor Katie Ives. “How well the Sherpas could do, how committed they seemed–that was the best marketing [for them to get hired again]. They wanted to be spoken well of. But there was a heavy toll of Sherpas dying.” Seven Sherpas were killed by a single avalanche during George Mallory’s 1922 attempt. For subsequent generations, as Jamling Tenzing Norgay recounts in Touching My Father’s Soul, expedition work often seemed like a kind of “mercenary military service”–a means of earning money that could help their families escape poverty, but that occasionally incurred a terrible cost.

[A] (Not shown.) Everest summit (8848m). [B] Lhotse (8516m). [C] Nuptse (7864m). [D] South Col (7906m). [E] Geneva Spur. [F] Lhotse Face. [G] Western Cwm. [H] Khumbu Icefall. [I] 2013 Camp I (6100m). [J] 2013 Camp II (6500m). [K] Location of argument with fixing team (7100m). [L] 2013 Camp III (ca. 7500m). [M] 2013 Camp IV (7906m). CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE. [Photo] Dick and Pip Smith/Hedgehoghouse.com

According to Richard Salisbury, who wrote the famed Himalayan Database with Elizabeth Hawley, seventy-three Sherpas and other indigenous high-altitude workers died on Everest between 1950 and spring 2012 alone. Untold others have suffered disabling injuries from mountain accidents or long-term health problems from prolonged hard labor at high altitude–at times leaving their families without a breadwinner. In 2012 Dawa Steven Sherpa wrote to Ives, “Sometimes the Sherpas’ huge efforts, loyalty and bravery is taken for granted. I have seen the physical and emotional toll that their work has on them, and it isn’t true that Sherpas don’t suffer on the mountains…. Sherpas do have fears on the mountain, do hurt in the thin air and do miss their wife and kids back home.”

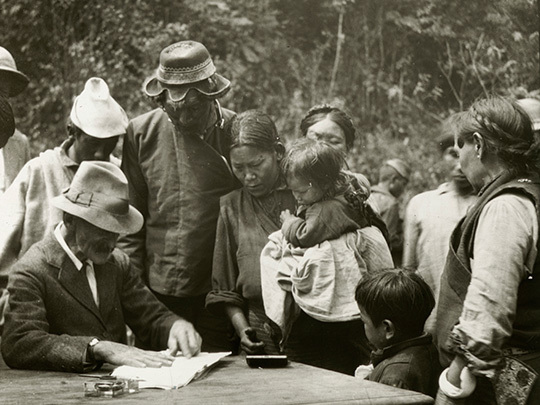

Amanda Padoan, mountain historian and co-author of Buried in the Sky, retells scenes from the early days:

Far from Everest, inside the pleasant temperature-controlled basement of the Royal Geographical Society, a photograph taken by John Noel in 1922 illustrates high-altitude labor relations. In the image, an Englishman points to a blank spot in a notebook while a Sherpani, bracing a toddler on her hip, juts out an inky thumb to roll a print. An anonymous Sherpa man, labeled “Coolie” in the library catalog, stands beside her. The woman and baby are his dependents, and, if he dies on Everest, the paymaster knows whom to give the Sherpa’s last wages.

By the 1930s, Sherpas had formed quasi labor unions, negotiating fairer wages and working conditions. They organized general strikes in 1933 and 1935. Ang Tharkay, who joined Eric Shipton’s reconnaissance of Everest in 1935, described one dispute in Memoires d’un Sherpa. “We got an order for each of us to carry a load of seventy pounds from Gangtok to Lachen. Since, in principle, carrying loads wasn’t something Sherpas did before base camp, we protested, deciding unanimously to strike.” En route to base camp, load carrying was relegated to members of other local ethnic groups, while the Sherpas dominated the more-lucrative upper mountain work. Occasionally a Tibetan Bhote, such as Tenzing Norgay, would break through and adopt a Sherpa role and identity, but the Sherpas’ influence was so robust that their ethnicity became synonymous with the profession.

Both collaboration and conflict between Sherpas and Westerners have long been part of Everest mountaineering, and the 1953 first ascent of Mt. Everest was no exception. Tenzing Norgay recounted how, at the launch of the expedition, the Sherpas were offered the hard floor of a garage to sleep on, while the sahibs enjoyed beds inside the British embassy. Tenzing Norgay, a full team member, refused his bed and chose to stay among the Sherpas as a sign of solidarity. The garage had no latrine, so the Sherpas urinated in front of the building in protest.

“[M]y story is not ‘official,'” Tenzing Norgay cautioned in his autobiography, Tiger of the Snows, co-authored with James Ramsey Ullman. “I am not an Englishman but a Sherpa.” The “unofficial” story goes on to describe Tenzing Norgay’s humiliation at a press conference soon after he and Edmund Hillary became the first to stand on Everest’s summit. Colonel John Hunt, the leader of the expedition, called the gathering to debunk rumors that Tenzing Norgay had reached the top ahead of Hillary. Hunt “lost his temper and implied that, far from being a hero, I wasn’t even, technically, a very good climber,” Tenzing Norgay explained. To the Nepali and Indian journalists, Hunt was “pouring kerosene on a fire.” Despite the myriad honors and recognitions Tenzing Norgay received after the first ascent of Everest, those two insults haunted him for the rest of his life.

During the 1963 American Everest Expedition, Sherpa members began regularly ferrying loads to high camps unaccompanied by their Western employers. And in the expedition account, Americans on Everest (1964), the US journalist James Ramsey Ullman recorded a sense of blending roles. Sherpas members argued successfully for the same access to oxygen use and the same number of sleeping bags as the Americans. “[The Sherpas] are dedicated,” Ullman noted, “to what they conceive to be their rights.” Once a few Sherpas were selected to be part of a summit bid, the American team members started to accord them the same status as “climbers.” Of the load hauling from Advance Base Camp, Ullman recounted:

The real job, during this phase of the climb, was being done by the Sherpas up on the Lhotse Face, and there was a glumly recurrent, though scarcely realistic, vision of their going on all the way to the top of the mountain while the sahibs cooled heels and behinds in the Western Cwm. THIRTEEN SHERPAS REACH SUMMIT OF EVEREST; AMERICANS GREET THEM ON DESCENT WITH CHEERS AND HOT TEA would be a fine message to send out to Kathmandu and the world beyond.

Twenty-eight years later, an event similar to that imaginary headline finally occurred. In 1991, ten Sherpas carried out the first Sherpa-only expedition to the summit of Everest–with a few Americans, including Athans, as support members to film and observe. Though the ascent has received relatively little media attention, it marked an important change in the perception of Sherpas on the mountain. “Sherpas were gaining more experience,” Athans says. “They could do all the work themselves…. [The goal of the Sherpa Everest Expedition] was to show that the role of Sherpas was changing beyond the image of Sherpas as only capable of carrying loads while the Westerners fixed the ropes. Summit day was a really great moment. The Sherpas had fixed the whole route, done all the decision making.”

The cold, gusty weather had tested their resolve, Athans recounted in the American Alpine Journal report: “A team composed of anyone other than Sherpas certainly would have chosen descent rather than continuing in the maelstrom of stinging, blinding snow.” At the top of the peak, the three summiters, Sonam Dendu, Apa and Ang Temba attached white prayer flags to an old yellow oxygen cylinder. A year later, their expedition leader Lopsang Sherpa explained to National Geographic, “We want to take pride as a people apart,” while Sonam Dendu said the ascent was intended “for all the Sherpas.”

In the decades after the expedition, Athans recalls, “We started to see Sherpas taking on greater and greater roles and responsibilities…. [There was] an increase in skill and proficiency. In some cases, they began doing all the guiding process.”

[A] (Not shown.) Everest summit (8848m). [B] Lhotse (8516m). [C] Nuptse (7864m). [D] South Col (7906m). [E] Geneva Spur. [F] Lhotse Face. [G] Western Cwm. [H] Khumbu Icefall. [I] 2013 Camp I (6100m). [J] 2013 Camp II (6500m). [K] Location of argument with fixing team (7100m). [L] 2013 Camp III (ca. 7500m). [M] 2013 Camp IV (7906m). CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE. [Photo] Dick and Pip Smith/Hedgehoghouse.com

EARLY ON APRIL 26, 2013, Chad Kellogg, Damian Benegas and Rory Stark met at the International Mountain Guides (IMG) camp near the base of the Lhotse Face with the intention of trying to fix a modern variation of 1953 route to Camp III. Once the Westerners decided that the route was feasible, two Sherpas–Mingma Tenzing of IMG and one other–joined them. “Everyone was happy,” says Benegas. Even though the 1953 route takes longer to fix and has a section exposed to serac fall, it’s faster and easier to carry loads up it, Benegas claimed. Others claim the direct route is faster and less dangerous.

While the three Westerners and two Sherpas were still fixing, Sherpas carrying loads started following them up the ropes, hoping to secure the best spots in Camp III for their teams. Four hours and several hundred vertical meters higher, the team halted at a large crevasse. Unable to circumvent the obstacle, they descended, stripping hours of work along the way.

“When we arrived to Camp II, there was a lot of grumbling from the Sherpa crew that we had wasted a day. They had wanted to fix the lines to Camp III themselves without the ‘white eyes,’ or mikaru, as the foreigners are known,” Chad Kellogg wrote in a blog post. “We came to find out that the fixing of the lines is a matter of national pride for the Sherpas.”

One Sherpa confronted Benegas. “He went off, and I went off,” Benegas says.

“Pride played a major role in this,” his brother Willie Benegas thinks. An awareness of the value of their work has been building within the Everest Sherpa community for years. “When I started climbing Everest in 1999 to 2006 or 2007, the Sherpas were not really pushing to fix ropes. They didn’t mind fixing up to the South Col, but not above that,” Benegas says.

Back then, from where those fixed ropes ended, Western guides would often haul their own lines, stringing up massive amounts of rope on their clients’ summit day. In 2009 Russell Brice guided the south side of Everest for the first time. That year also marked the first time companies discussed fixing ropes up to the top of the mountain prior to summit day. “There was considerable opposition to doing this, however IMG, AAI and HimEx did end up fixing in advance,” Brice explains. “This has since become normal practice and much more refined with better rope, same color rope and better quality fixation.”

Along with that change came another evolution: Sherpas soon had a major part in rope fixing from the base of Everest’s south side to the very summit. Today, their job involves some of the most dangerous labor on the mountain and represents one of the most important pieces of the commercial guiding effort. “It is fair to say that the largest bulk of the work on the mountain is done by the Sherpas,” Dawa Steven Sherpa told Ives in May 2012. “Sherpas have also evolved from simply being a ‘high altitude porter.’ For example, twenty-five Nepalis (mostly Sherpas) received their UIAGM certification this week. As far as qualifications go, they are now on par with Western guides.” Ngawang Nima Sherpa, of the Nepal Mountaineering Instructors Association, added, “Most of us know that the 8000-meter ascent is the toughest job in the world, in which our [Nepali and Sherpa] climbers take the international climbers to the top of the mountain.”

But while Sherpas’ responsibilities have grown, their salaries have generally remained lower than those of their Western coworkers. “In Nepalese terms, the Sherpas are paid very well per expedition, several times more than the average annual [income]. However, the Sherpas are still paid less than the Western guide,” Dawa Steven Sherpa explained.

While several companies declined to make their pay structures public, Alpenglow Expeditions shared their numbers with us. Sherpas receive an up-front “signing bonus” of approximately $2,000, Ballinger says, then a $15 daily wage. On top of that, Alpenglow pays a carrying bonus for each load Sherpas haul between camps. In 2013, their bonus was $20 for carrying a 15kg (33lb) load from Base Camp to Camp I, $15 to Camp II, $50 to Camp III, $60 to Camp IV, $500 to the summit. “So for every 33 pounds carried to from Base Camp to Camp IV, a Sherpa made a $145 bonus,” he says. “[We pay] an additional $500 for summiting (we actually pay these summit bonuses even if a Sherpa turns around with a client, or stays in Camp IV in support).” Finally, clients are encouraged to give the Sherpas who climb with them to the summit a $500-$1,000 tip.

At the end of the season, Sherpas will return home from Everest with $6,000-$8,000, Ballinger says. “Western guides have a much bigger range. There are many guide companies, including most of the big-name US companies (not Alpenglow) that do not pay their first-time guides anything. Only their expenses are paid on their first season. From there, wages run the gamut. I have heard of Western guides making as little as nothing and as much as $50,000 for the two-and-a-half month season. The major company I worked for from 2007-2012 paid between $18,000 [and] $30,000 [to Western guides] depending on experience for the Everest season. Alpenglow has a similar range based on AMGA/IFMGA level of certification and previous Everest experience. Overall, no, Sherpa and Western guides are not paid similar wages.”

Ballinger cited Nepalis’ lower cost of living and training expenses as reasons for the discrepancy. “AMGA/IFMGA certification [can cost] $25,000 while the Khumbu Climbing Center costs less than $100. Of course not all Western guides have their AMGA/IFMGA guide’s qualification, and not all Sherpa have been to the KCC. I believe these qualifications should be required of both groups, as a minimum for guiding and working on Everest,” he says.

Looked at from another perspective, one might note that, with a few exceptions (Russell Brice told the journalist Ed Douglas that he pays one of his Sherpas, Phurba Tashi, the same amount as Western guides receive), certain Everest workers who have similar years of experience, who are confronting life-threatening risks and who are entrusted with significant levels of responsibility, don’t have the same opportunities to earn higher wages and advancement as their peers do–mainly because of their nationality.

Although there are a few Sherpa-owned guiding companies, Luis Benitez, an 8000-meter peak guide from Colorado, points out that Sherpas sometimes lack the access to medical, business and technical education–as well as the financial resources or the Internet marketing skills–to break away from their dependence on Western outfitters and to attract their own international clients or sponsors.

In 2010, a client hired Benitez and a Sherpa, Lakpa Rita, for Broad Peak and K2. “Lakpa lives in Seattle,” Benitez says, “is a senior guide, leads expeditions with Westerners as assistants, has climbed the Seven Summits and still doesn’t get paid every trip as much as the Western guides he works with.” During their Broad Peak/K2 trip, Benitez made $2,000 more than Lakpa Rita because he handled the logistics and because the client was his contact. “Is that difference worth 2k?” Benitez asks. “Lakpa Rita did carries to high camps on Broad Peak and K2. In reflection I would say that [his work] more than made the argument for equal pay, yet here I sit as guilty as anyone else. Until Sherpas get that medical/business/social media training, this disparity will continue. The guiding community needs to change the game by changing the questions they are asking themselves: How willing are we to lean in and provide Sherpas with a different kind of education and support?”

Everest, by “Fair Means”

THE 2013 SEASON STARTED OUT as the most promising in years for lightweight adventure climbing on Everest, a historic endeavor oft-forgotten amid modern lamentations about overcrowding and dangerously inexperienced clients. While the first ascent of the peak set a precedent for large sieges, other early aspirants, such as Eric Shipton, had argued for the value of smaller groups and more minimalist styles. In 1978 Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler finally proved it was possible to climb the world’s highest mountain without supplemental oxygen. Two years later, Messner returned for an alpine-style solo of the North Face. Everest climber and historian Ed Webster calls Messner’s 1980 summit, “the purest ascent of Everest possible.”

“Messner and Habeler had raised the bar,” Lincoln Hall recounted in 2008. “An oxygenless first ascent was the next big challenge and we embraced it” (Alpinist 27). In 1984 Hall’s five-man Australian team established a new Everest North Face route, White Limbo, with the help of Nepalis Tenzing Sherpa and Narayan Shresta. None of the climbers used supplemental oxygen. After fixing ropes to 7400 meters, Tim Macartney-Snape, Lincoln Hall, Greg Mortimer and Andrew Henderson continued in a single push up icy rock and loose snow. Jim Wickwire, who watched their progress from a distance, called it, “One of the most amazing achievements yet on Everest” (1985 American Alpine Journal).

[A] (Not shown.) Everest summit (8848m). [B] Lhotse (8516m). [C] Nuptse (7864m). [D] South Col (7906m). [E] Geneva Spur. [F] Lhotse Face. [G] Western Cwm. [H] Khumbu Icefall. [I] 2013 Camp I (6100m). [J] 2013 Camp II (6500m). [K] Location of argument with fixing team (7100m). [L] 2013 Camp III (ca. 7500m). [M] 2013 Camp IV (7906m). CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE. [Photo] Dick and Pip Smith/Hedgehoghouse.com

Outside of the alpine-climbing community, many people forget the Swiss alpinists Erhard Loretan and Jean Troillet’s 1986 “night-naked” speed ascent of the Supercouloir. Without any ropes, oxygen bottles, high-altitude porters or even tents, they blitzed up the mountain and back down in a mere forty-three hours.

And in 1988, two Americans, one Canadian and one Brit–Ed Webster, Robert Anderson, Paul Teare and Stephen Venables–climbed the steep ice and rock walls of the untouched Neverest Buttress in relatively light style, fixing only the lower sections. “On Everest,” Webster later wrote in Alpinist 27, “the landscape you experience may be the one you create within you. By forgoing oxygen and by climbing in a small, unsupported group, we encountered both the mountain’s unmitigated force and its wildest beauty.”

Adventure climbing dwindled with the rise of commercial expeditions in the 1990s, and by the 2000s, the mountain had been swallowed by the hordes of peak baggers and the flurry of mainstream media reports recounting their scandals, disasters and Everest “firsts.” In 2008, Chris Bonington, leader of the 1975 first ascent of the Southwest Face, told Ives that it seemed as if few people still recalled the richness of the adventure heritage of the mountain.

The goals announced for 2013 hinted at the beginning of a partial renaissance–if successful. Alexey Bolotov and Denis Urubko planned a bold, and wholly new route on the Southwest Face in lightweight style. Most closely followed by climbing media were the efforts of sponsored climbers Moro, Steck and Griffith, who planned to link the Hornbein Couloir with a new route on Lhotse. The Everest-Lhotse linkup could represent one section of a long-dreamed-of traverse of Everest, Lhotse and Nuptse. Neither climb would be in pure alpine style: they would pay to use the ladders in the Khumbu Icefall, which are placed each season by the “Icefall Doctors,” a group of Sherpas who work for the Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee (SPCC), a local NGO. But, otherwise, they intended to climb without hired high-altitude assistance or fixed ropes. First, however, both groups decided to acclimatize on the south side’s normal route, thus crossing deeper into terrain that had long become the realm of siege-style expeditions and commercial teams.

A Curse, a Fight and the Aftermath

ON APRIL 27, AFTER THE FAILED DAY of rope fixing, Kellogg, Damian Benegas and Rory Stark stepped down from the fixing team, and the Sherpa crew of sixteen started up the Lhotse Face to fix the direct line. The same morning, Jonathan Griffith, Simone Moro and Ueli Steck departed Camp II for their tents at Camp III. Despite later rumors that Moro’s team didn’t have the requisite permit, Griffith confirms that they had the three permits necessary to acclimatize and to attempt their linkup of the Hornbein Couloir and Lhotse–a $70,000 Everest permit split among seven climbers, a permit for the West Ridge and one for Lhotse. On their way to the face, the three European climbers met a Western guide, Griffith said in a letter to UKClimbing.com. Steck explained their intention: to free solo up the Lhotse Face to Camp III. The guide told them, “OK,” but warned them not to touch the fixed lines or get in the way of the working Sherpas. The trio agreed.

In a National Geographic interview, Moro said he assumed that the Sherpas thought they planned to hang on the fixed ropes, and that as long as he and his partners didn’t do so, there would be no problem. As the three climbers soloed, they kept a distance of 50 meters from the fixing team and their ropes, Griffith wrote in an April 29 press release. Moro reported a distance of 100 meters. He also said two Sherpas knocked ice down on Steck’s head, but they continued upward.

After sixty to ninety minutes, the trio said they reached a point just above their tent at Camp III. They traversed right to a stance where three or four Sherpas had gathered. The lead Sherpa was fixing ropes fifteen to twenty meters above. Griffith crossed the ropes first and continued traversing on a snow ramp. When Steck arrived at the stance, the head of the rope-fixing team, Mingma Tenzing Sherpa of IMG, shouted and rappelled down to confront the climbers.

“As Ueli was soloing and therefore not attached to a rope it was natural that he should hold his hands up to take the impact of the force arriving on him from the lead climber abseiling right on to him,” Griffith wrote in the release. “This prompted the lead climber to accuse Ueli Steck of ‘touching him.’ In between hitting the ice with all his force and screaming at Ueli Steck ‘why you touch me’ he said that they had kicked ice down on them and injured a Sherpa.” (Later that day, a Sherpa reportedly explained to his sirdar that he bled from his nose because he slipped while jumaring and hit his face on the ice.) Steck offered to help fix the rope up to Camp III, a suggestion that some of the Sherpas perceived to be an insult. One of them, Karma Sarki, later told Outside Senior Editor Grayson Schaffer, “The Sherpas were furious because the three climbers had overtaken us, and they did so in our country, on our mountain. We put our lives at risk for climbing Everest and helping the foreign climbers. Everest is everything for us.”

During the heated back-and-forth, Moro, who had traversed over to join them, called one of the Sherpa men machikne, a Nepali insult similar to, but carrying even greater weight than, “motherfucker.” Mingma Tenzing Sherpa ordered the fixing crew back to Camp II. Steck fixed the final 260 meters to Camp III, and Moro spoke with Greg Vernovage of IMG in Camp II. During the conversation Moro cursed again. His harsh words transmitted across Camp II through the open radio frequency and into the ears of Westerners and Sherpas alike.

“Moro’s casual use of profanity in his non-native language rubbed both the Sherpas and the Western guides the wrong way at the time,” One Mountain Thousand Summits author Freddie Wilkinson recently wrote in Men’s Journal. Himalayan Ascent co-owner and Nepali guide Sumit Joshi told Wilkinson, “Simone is a funny guy. But he’s always cutting jokes and swearing, and that wasn’t well received.”

The trio descended to Camp II, and Vernovage joined them at their tent when they arrived. “He said that the Sherpas were really pissed about Simone swearing,” Steck told Outside. Moro says he radioed to the Sherpa fixing team, saying, “We are here in Camp II, and I want to come to your camp and talk with you.”

Meanwhile, the Sherpa fixing team had grown into a larger group (various reports number the crowd from dozen people to upward of 100), some outwardly angry, others curious bystanders. A sponsored American climber, Melissa Arnot, ran ahead to warn Griffith, Steck and Moro. They came out of their tent to meet the crowd of Sherpas, some of whom covered their faces and carried rocks.

[A] (Not shown.) Everest summit (8848m). [B] Lhotse (8516m). [C] Nuptse (7864m). [D] South Col (7906m). [E] Geneva Spur. [F] Lhotse Face. [G] Western Cwm. [H] Khumbu Icefall. [I] 2013 Camp I (6100m). [J] 2013 Camp II (6500m). [K] Location of argument with fixing team (7100m). [L] 2013 Camp III (ca. 7500m). [M] 2013 Camp IV (7906m). CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE. [Photo] Dick and Pip Smith/Hedgehoghouse.com

“This is when I came in between this mob, not wanting to see a death,” says Marty Schmidt, who was later accused on Garrett Madison’s blog of being a “careless Western climber” who threw the first punch–an act that Schmidt denies.

“I asked several Sherpas to put the stones down,” he explains. “[I was] kicked several times, then hit hard with a stone, then punched in the eye, this time I hit back in self defense, which shocked them.” A fight ensued. Several Sherpas aimed rocks, kicks and punches at the Europeans.

Arnot, Vernovage and Phunuru Sherpa, of IMG, separated the Westerners and Sherpas. Schmidt found Steck, who had been hit in the head with a rock, and brought him into a tent, while Griffith and Moro hid behind a rock.

“From inside, I could just see Melissa and Greg standing in front of the tent with all these people who were saying to get me out and that they were going to kill me first,” Steck told Outside. “In the meantime, they were throwing huge rocks into the tent, the kind that, if they hit you in the head, you’d be dead immediately.”

The Sherpas outside asked that the expedition leader apologize and threatened more violence if he refused. A Sherpa climber from the Europeans’ camp discretely brought Moro into the tent while Griffith stayed hidden, Griffith and Steck explained. Moro emerged from the tent to apologize, and some angry Sherpas punched him again. He came out again, this time on his knees, saying “Sorry! Sorry! Sorry!” He says they kicked him and threw a small knife at him, which bounced off the hip belt of his backpack that he had removed.

Moro told National Geographic that the Sherpas said, “Okay, we give you one hour. In one hour, you have to fetch your tent and run away from here. And if you’re here after one hour, we will kill you.”

As the trio descended to base camp, they avoided the established route. “We were on a mission, going into deep valleys and crevasses and checking over our shoulders to see if they were coming after us,” Steck told Outside. “We crawled on our knees so they couldn’t see us. Then we snuck down the route as far as possible to a big ladder, because if they chased us, I knew we could cross that ladder and then cut it loose so they couldn’t follow. That was the plan.” Though they traveled through the heavily crevassed terrain with no ropes, they arrived at the base of the mountain without further mishap. “I don’t know how the hell we made it through without falling into a hole,” Griffith says. “But it felt like the safest place on earth as we could see the Sherpas lining the ridges of Camp II watching us but knew they wouldn’t dare follow us in there.”

It’s important to note that a number of other accounts surfaced on the Internet shortly after these events, some written by climbers who weren’t present at the incident and who received their information second-hand. Mike Hamill of IMG reported on their expedition blog that several Sherpas had told them to stay off the Lhotse Face on their approach. “The two foreigners passed off this repeated request from a handful of Sherpas with the swipe of a hand and nod of the head stating clearly, ‘We will do as we please; we are going climbing on this route.'” Hamill wrote. (“Can you ever imagine anyone actually saying those exact words? [T]o present them as a direct quote is just embarrassing,” Griffith wrote to Alpinist afterward.) Garrett Madison of AAI reported that Simone radioed from the Lhotse Face that he would go down to Camp II and “fucking fight” the Sherpa fixing team. (Moro vehemently denies saying this.)

Sumit Joshi and his business partner Lakpa Sherpa, who were in Camp II during the disagreement, also recounted a different version of events on Himalayan Ascent’s blog:

When the three climbers arrived into Camp II, the fixing team [was] ready to meet them. Everyone else at Camp II [was] also anticipating the ‘meeting….’ Simone was apparently reluctant to offer an immediate apology and eventually the fixing team became impatient, so they walked into the group’s camp to talk to Simone directly. To the many Western bystanders watching, this may have seemed like the fixing team were going into the camp to fight. The fixing team threw rocks at the tent to get the group to come out…. One western guide tackled a Sherpa carrying a rock perhaps thinking he was going to throw it to hurt someone. Unfortunately, this first assault on the fixing team triggered them to respond aggressively.

…[W]e saw some 30 Sherpas and other bystanders just WATCHING witnessing the event. Reports claiming that 100-200 Sherpas attacked the three climbers are entirely FALSE. Only the fixing team were involved. The bystanders may have been perceived as being a part of the aggressive “mob.” We also did not witness other claims that rocks were used to hit others, and that Simone was stabbed by a penknife hitting his backpack waist strap (he wasn’t wearing a backpack). During the times that Simone did come out to make his apology on his knees, we did see the unfortunate slap and kick. Sure the fixing team [was] feeling quite incensed, but they weren’t fired up to kill anyone. Eventually the apology was accepted and the group disappeared to BC.

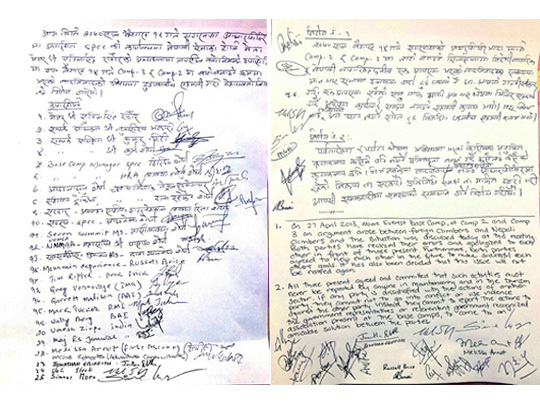

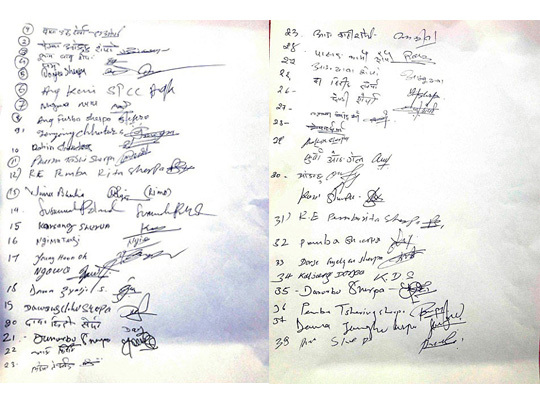

After apologizing privately to Mingma Tenzing Sherpa, Moro stated his regret for using foul language at an organized peace treaty in Base Camp. The Sherpas involved also apologized. Everyone present signed an agreement that read, in Nepali and English:

Today, on 2070 Bhaishak 16 (April 29, 2013) at Everest base camp at SPCC [Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee] office, with the presence of the Chief of Nepal Army team leader, Major Sunilsingh Rathor and the following attended personnel agreed to do the following decisions regarding the arguments between the two groups on April 27 while fixing ropes between Camp 2 and Camp 3.

On April 27, 2013, above Everest Base Camp, at Camp 2 and Camp 3 an argument arose between foreign climbers and Nepali climbers and the situation was discussed today at this meeting. Both parties have realized their errors and apologized to each other in front of those present. Furthermore, both parties agreed to help each other in the future to make successful each other’s goals. It has also been decided that this issue will not be raised again.

All those present agreed and committed that such activities must never be repeated by anyone in mountaineering and in the tourism sector. If any party is dissatisfied with the actions of another party, they commit not to go into conflict or use violence against the other party. Instead they commit to report the actions to the government representatives or relevant government recognized association present at the base camps, to come to an amicable solution between the parties.

Nearly 40 Western and Sherpa climbers signed the handwritten agreement.

[A] (Not shown.) Everest summit (8848m). [B] Lhotse (8516m). [C] Nuptse (7864m). [D] South Col (7906m). [E] Geneva Spur. [F] Lhotse Face. [G] Western Cwm. [H] Khumbu Icefall. [I] 2013 Camp I (6100m). [J] 2013 Camp II (6500m). [K] Location of argument with fixing team (7100m). [L] 2013 Camp III (ca. 7500m). [M] 2013 Camp IV (7906m). CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE. [Photo] Dick and Pip Smith/Hedgehoghouse.com

“I knew it was important to change the relation between Sherpas and foreigners,” Moro said in a National Geographic interview afterward. “Without Sherpas, nobody climbs Everest. Without foreigners, there are no jobs for Sherpas. This concept is too often forgotten.”

“Some people treat the Sherpas really bad, like slaves,” Steck told The New Yorker writer Nick Paumgarten. “I don’t want to be the face for this.”

Steck and Griffith returned to their homes in Europe, but they continue to suffer recurring nightmares. Moro chose to remain on Everest to pilot helicopter rescues, offering these services to Sherpas for free. Not long after the fight, he helped recover the body of a Sherpa who had died while working. The commercial expeditions moved ahead with their summit attempts. Several guides wrote blog posts emphasizing a happy return to business as usual. Between May 17 and 25, Alan Arnette reported on his season recap, more than 500 people reached the summit of Everest; one hundred fifty summited on May 19 alone.

But few seem to agree that any real resolution came out of the ceremony. Steck told Wilkinson, “I think this ‘ceremony’ calmed the situation down, but it certainly did not solve the problem. This ‘peace deal’ was just a pretext for everyone to get out of the situation.”

A Turning Point?

ALEXEY BOLOTOV AND DENIS URUBKO were on another part of the mountain when the fight occurred. In the subsequent weeks, they continued preparing for their own light-style attempt on the Southwest Face.

On May 15, while acclimatizing, Bolotov fell 300 meters to an instant death when his rope broke on rappel. Urubko left the mountain, too, with his partner’s body.

From May 15 to May 21, the British guide Kenton Cool and the Nepali Glygen Sherpa completed the “Khumbu Triple Crown,” linking Everest, Nuptse and Lhotse, but relying on pre-established camps and on the fixed ropes of commercial expeditions for all three peaks.

“When I first thought about climbing the trilogy some three years ago,” Cool told Alpinist, “I thought Nuptse would be done alpine style. It would make a great route that way. Deep down, I wish I had climbed it that way.” The question of whether anyone will ever be able to complete the enchainment or make the true “Everest Horseshoe” traverse in alpine style remains unclear. Even if a climbing team were capable of traversing the three peaks, all over 7800 meters high, in a single push, the commercial guiding infrastructure could present a hurdle no one can negotiate.

“I think we will only know the real impact of what happened this spring by the changes that take place next spring,” says the anthropologist Janice Sacherer Turner, who has spent many years studying Himalayan cultures. “In retrospect, the world of alpinists may…come to realize that their chances for doing the sorts of routes that Moro, Steck, Urubko and others hoped to establish on Everest was permanently hindered by what happened.”

Commercial operators are reportedly advocating for official closure of sections of the mountain during rope fixing, and for a declaration of this closure to be printed on each climbing permit, Wilkinson wrote in his Men’s Journal article. While few alpinists seeking to climb new routes in lightweight style have paid much attention to Everest in recent decades, and the route preparation of the Khumbu Icefall has already eliminated the possibility of a pure-alpine-style ascent from that side, this further domination of the mountain by commercial teams could make adventure climbing even more difficult. “If they say the mountain is closed until the ropes are fixed, then this really is the death knell for adventure on Everest,” former American Alpine Club President Mark Richey told him.

Ed Webster disagrees. In an email to Alpinist, he wrote that even if both the Chinese and Nepali governments enforced temporary closures:

There’s been precious little ‘adventure’ on Everest’s two standard ascents, the South Col route in Nepal, and the North Col/Mallory route in Tibet, for decades…. Fortunately, there are a multitude of difficult climbs up Everest that ascend other major faces and ridges…. On Everest’s north side not a single hard “adventure” route branches off of the North Col/Mallory Route, so the peak’s north-facing aspect would be completely unaffected by a two-week “fixed-rope” closure. Climbers taking on an alpine-style ascent of any of the sustained North Face routes–the American Direct, White Limbo, or the Super Couloir (Japanese and Hornbein Couloirs combined)–start miles away from the North Col. And, obviously, no lines-in-waiting at the base of the Kangshung Face of Everest either. No problem there! The only routes, and “adventures,” possibly complicated by a temporary climbing ban would be routes up Everest’s Southwest Face, since the Khumbu Icefall must be navigated.

DAWA STEVEN SHERPA TOLD PAUMGARTEN that he thought the fight was merely a result of “one small thing between a few egomaniacs.” But for some Nepali and Sherpa climbers who have relied on their work on the mountain for generations, the fallout reflects much more than a dispute about style preference or the bickering of a few altitude-affected men.

Sumit Joshi and Lakpa Sherpa write:

This dispute was not really about a turf battle between three foreign alpine climbers and a fixing Sherpa team. It certainly wasn’t about Sherpas feeling jealous of western guides or threatened by western alpine climbers. As…[alluded to] by others, the fixing team was venting the frustration of all highly skilled and experienced Sherpa climbers who want to feel more respect from their fellow western colleagues. For years they have quietly suffered and endured arrogance displayed by some western guides and professional climbers…. They know the mountains here like no other western climber, and commercial expeditions admit they cannot operate in Nepal without Sherpa support. After more than 60 years of climbing alongside their western colleagues, helping them to achieve first ascent glories on 8000m mountains, it’s a small request from humble mountain men.

As a Nepali-owned outfitter, we often hear our western outfitter friends acknowledge that the skilled Sherpa climbers deserve more. But what are they actually willing to give more of? More money? More benefits? More fame? Perhaps they should start with more respect.

“These Sherpas had a right to express themselves,” Marty Schmidt now says of the men who struck him, “but they had no right to hurt another soul.”

[CORRECTION: The date of the rope-fixing meeting was April 25, not April 18, as previously written.]