Editor’s Note: Alpinist 30 is currently at the printer and will be shipped to subscribers and retail stores soon. In this upcoming issue, Don Mellor writes a Crag Report “Told in Stone: Stories from the Adirondacks’ Wallface Mountain.” His personal history documents a single wall. At 800 feet high, it’s one of the tallest in the eastern United States. But Wallface is just one small piece of the park’s history: a record that stretches back generations, a record easily erased by time and moss.

Based in Burlington, Vermont, Matt McCormick has made the ‘Dacks his climbing headquarters for two years. While Mellor provides a peek into the past in Alpinist 30, McCormick–one of the Northeast’s strongest emerging climbers–offers a vision of the future in this online exclusive. Pick up a copy of Issue 30 or subscribe to Alpinist for the full scoop.

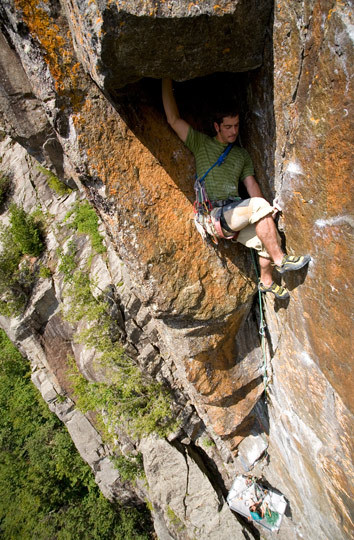

The author fiddles with a gear placement before the final runout crux on Zabba (5.13a), Spider’s Web, Keene Valley, Adirondack Park, New York. The hard classic is known for its limited and tenuous gear. [Photo] Dave Vuono

The sky darkened over Rumney. Dozens of crag rats scurried to squeeze in pitches before the rain. For once, I was more interested in a conversation than in climbing.

I had spotted a well-known climber from California. Though I had never met him before, word of his hard trad ascents got me excited to chat about the potential for such things outside of Rumney. I introduced myself, and we began talking about projects around other parts of New Hampshire. Conversation moved to the Gunks. Then he asked: “What about that place… the A-dron-o-dacks?”

I cringed. “You mean the Adirondacks?”

“Oh yeah. That place looks sick!” he said. “But I don’t think I’ll make it there this trip.”

This well-traveled visitor is not alone in his Adirondacks cluelessness. I’ve heard dozens of similar mispronunciations. Once I even saw a classic ‘Dacks route featured in a climbing magazine with the caption: So and so sending in the “Nacks of Maine.” While the Adirondacks in New York might be foreign to the majority of North America’s climbers, even climbers in the Northeast, the area has a rich climbing history. It also has a small and dedicated crew who, still today, continue to uncover new cliffs and envision potential for new lines on the blankest faces.

The Park

The Adirondack State Park of New York is the largest government-protected area in the contiguous United States. To give you a sense of scale, its 6 million acres is roughly the size of New Hampshire. Scattered throughout the park are hundreds of crags. While some are lichen-covered chosspiles, many house some of the most beautiful rock climbs in the country. Splitter cracks stretch hundreds of feet high, rising out of dense forests and thick moss. Slabs lay low; dark roofs overhang ominously. Edges and ledges speckle the cliffs’ clean anorthosite–the same kind of metamorphosed granite found on the lunar landscape.

Peter Kamitses on Illuminescence (5.13d), Moss Cliff, Adirondacks. The right side of this crag was predominantly an aid-climber’s paradise until Kamitses unlocked this route and Fire in the Sky (5.13c). Both are steep and runout. [Photo] Dave Vuono

In 2008, local climbers Jim Lawyer and Jeremy Haas released a new guidebook to the ‘Dacks. The huge 650-page book teems with beautiful topos and detailed descriptions for more than 1,900 routes. Its sheer size, however, has become a standing joke among friends: “You take the rope and rack. I’ll take the guidebook.”

So, it’s a wonder that so few climbers live here, or even travel here. Often, the crags are so quiet that the anorthosite seems appropriate–the experience is so solitary that it’s like climbing on the moon.

One big reason is that the climbing is an “acquired taste.” Developing new routes in the ‘Dacks means dealing with all the unpleasantries that the northeast is infamous for: sticky heat, bitter cold, unrelenting bugs and the dirty process of cleaning.

Jeremy “Rowdy” Dowdy embraces It’s Only Entertainment (5.11+), Spider’s Web, Keene Valley, Adirondacks. [Photo] Dave Vuono

Another reason is accessibility. Most of the park sits a long way from a large population center. And the ‘Dacks are so big that it takes almost five hours to drive across the park east-west and south-north. Some crags are so isolated from others that development has been region-specific. The climbing community is fragmented into geographical cliques that frequent either the southern crags around Lake George and the Southern Mountains or Keene Valley and the High Peaks.

And the climbing is no sport playground. Infused into the Adirondack climbing experience is a dedication to clean ethics. While there is not a strict ban on bolting or the use of fixed anchors, climbers generally respect the expectation that bolts will be used conservatively, only where no natural protection exists. Some crags, such as the Spider’s Web in Keene Valley, have almost no bolts.

The enormity of writing a guidebook to an area of this size required a full-time commitment from the authors. Lawyer alone spent two years on the project and logged more than 30,000 miles in his vehicle, scouting crags and talking to climbers in New York, Vermont and beyond. Collecting information on first ascents was difficult not only because of the park’s size, but also because the history, too, was fragmented crag-to-crag and, over time, lost in collective amnesia.

The Explorer-climbers

“The explorer-climber is often a different breed from the typical climber. The explorer-climber studies topo maps to ferret out the steep faces, and systematically visits every squeezed concentration of contour lines until paydirt. A few routes get climbed and they move on; the joy is in the discovery. Subsequent visitors, sometimes armed with more skill or sometimes just a different eye, build on their work and uncover more gems.” –Jim Lawyer

Over the last several years, a small but motivated group of explorer-climbers–like Lawyer, Colin Loher and Don Mellor–have been crawling throughout the park, unearthing new crags. Future Adirondacks climbers owe much to these modern-day pioneers.

But still, the relative obscurity of the Adirondacks has delayed development of difficult climbs. The park’s first 5.12 wasn’t established until 1987, by a visiting climber: Dave Lanman, a Gunks local. A year later, he returned again to bump up the grade with Salad Days, the park’s first 5.13. Though Salad Days takes an obvious line at the prominent roadside crag Poke-o-Moonshine, the climb was established more than a decade after the country’s first recorded 5.13.

Will Mayo on Fecalator (M10), Adirondacks. The climb was first established by Chris Thomas and is one of the Northeast’s hardest mixed climbs. Mayo nabbed the second ascent and was first to place all gear on lead. [Photo] Dave Vuono

Another of the first climbers to bring their 5.13 abilities to the park was southern Adirondack local Fred Abbuhl. In 1995 Abbuhl stumbled onto a beautiful crag in the central section of the park while he and his father were hunting deer. After following his father’s tracks for several hours, Abbuhl found his father eating lunch at the base of what would become known as Lost Hunter’s Crag. “Howdya like this crag I found for you?” Abbuhl’s father reportedly said.

Throughout the 1990s, Abbuhl quietly went on to establish several high-quality routes there, up to 5.13. As far as the record goes, most are unrepeated. “After their initial ascents, these routes have drifted into obscurity due to lack of attention,” Lawyer said in an interview. “There are just not enough climbers around here, at least not enough that climb at that level and are willing to walk.”

Of the many unnoticed ascents in the park, perhaps most significant was Dave Aldous’ 1996 ascent of Zabba (5.13a) at the Spider’s Web. Although Aldous later focused most of his time at the Gunks, he says the ‘Dacks will always feel like “my place.”

All ascents of Zabba (5.13a) have followed a line of crimps left of an obvious crack line at the base of the route. Nick Wakeman has been projecting the direct variation, which will most likely bump the grade to 5.13b. [Photo] Dave Vuono

“I’ve spent hours and hours of time hanging on the side of some new cliff with a wire brush in my hand scraping off lichen just so I could see if it would go,” Aldous said. “That feeling of solitude, I guess, is what I really like.”

The Spider’s Web is a contender for one of the best single-pitch crack-climbing crags in the country, and Zabba is one of its finest routes. For its relatively short height (80′), the route packs a punch right off the ground with a section of flaring 5.12c tips to the route’s crux, a balancy hand-foot match with the last gear several feet below. It took Aldous more than a month of obsessive toprope-soloing to work out the moves and gear placements before he returned to redpoint Zabba on lead. So unknown was his ascent that, in 2005, Vermont climber Peter Kamitses believed he had made the first free ascent. Despite its caliber, the route has likely seen fewer than 10 redpoints in 15 years.

For the past decade, Kamitses has been humbly amassing an impressive list of hard 5.14+ sends throughout the country. Having gotten a taste of what the ‘Dacks had to offer, Kamitses turned his abilities to a 300-foot overhanging “aid wall” called of Moss Cliff.

This black- and tan-streaked wall in Wilmington Notch in the Adirondacks is split by three amazing crack systems that would appear more natural in Yosemite than northern New York. Kamitses had seen a photo of the wall and heard many rumors about its free-climbing potential, but he did not make the trip from Burlington until 2006, when he climbed Creation of the World (5.11b, 4 pitches), the infamous offwidth that climbs the left side of the big-wall section of Moss Cliff.

New Hampshire-based climber Dave Sharratt joined Kamitses in September 2006 with hopes of freeing the steep aid lines. Together, they free climbed Fire in the Sky (5.13b, 4 pitches). The route combines sections of two aid routes called Children and Alcohol, and Mosscalito via a series of overhanging cracks and face climbing. Kamitses returned a week later to eliminate a hanging belay between the last two pitches creating a monster 140′ 5.13c pitch. He logged several 30’+ falls onto solid but well spaced cams battling the pump near top of the pitch.

Not finished with the wall, Kamitses established Illuminescence (5.13d)–just right of Fire in the Sky–a month later, in October 2006. He returned yet again to link the crux pitches of both routes, creating Ill Fire, the park’s first 5.14a in September of 2008. This wall remains one of the most impressive pieces of rock east of the Mississippi, yet Kamitses’ routes have seen only one repeat by Quebecois strongman Jean-Pierre Ouellet, who repeated Fire in the Sky soon after its first ascent. In the summer of 2008, Kamitses established Brass Balls, Sticky Rubber and Steel Nuts. This 5.12+ route tackles a beautiful arete with several well-spaced #3 rp and purple C3 placements for gear. It may come as no shock that this route, too, remains unrepeated.

Peter Kamitses 50 meters into the crux pitch of Illuminescence (5.13d). In September 2008, he combined the crux sections of this route and Fire in the Sky to establish a 5.14a variation. [Photo] Dave Vuono

Peter Kamitses has ushered a new era of hard trad in the ‘Dacks. Before his arrival, few climbers of his ability–if any–had spent significant time in the park.

Inspired by Peter’s ascents at Moss Cliff, I turned my own sights on a line on the Upper Washbowl Cliff in the Adirondacks’ Keene Valley. Upper Washbowl is an imposing 350′ wall that towers above Chapel Pond Pass, a popular after-climbing swimming hole. I had often looked at a perfect left-to-right arching dihedral that tracked up the wall’s prow. For many years, I assumed there were good reasons it had never been climbed. Finally after some inquiries, I found that the route had been passed off as “too hard looking.” And to local climbers, the steep and crackless first pitch just “didn’t look all that appealing.”

The author establishing a new ‘Dacks classic: Northern Revival (5.12c), Upper Washbowl, Keene Valley. [Photo] Dave Vuono

I proceed to clean off the first three pitches, placing four bolts where absolutely needed. I then discovered some of the most amazing rock climbing and exposure that I have ever experienced in the Northeast. The first pitch went at a bit scary 5.11a to a belay below the signature dihedral. Bouldery sequences reminiscent of sport climbing in Rumney led way to stemming and chimneying up the dihedral using four purple C3s and a gray C3 for protection. At times the climbing was runout, but never beyond reason. A final victory romp up an exposed 5.10a arete led to the top.

I called the route Northern Revival (5.12c). The new line did not only have stellar climbing, but it had stared climbers in the face for decades, since before I was even born.

The Future

The history of hard rock climbing in the ‘Dacks is a young one compared to most other climbing areas around the country. Projects still exist, not just on rarely visited backcountry bluffs, but also on classic roadside crags.

I myself found one just last summer. Spider’s Web is one of the park’s most popular crags, not least because it contains one of the highest concentrations of hard crack climbs outside of Indian Creek. One day I noticed an incipient seam creeping up the middle of the crag. It had been spotted previously but, like Northern Revival, the line had been dismissed as too hard and difficult to protect. In early July, I decided to clean the seam and have a closer look for myself. I found some marginal gear placements. Immediately I became obsessed–so obsessed that my friend Jamie Hamilton, seeing its effect on me, began calling it the “demon route.” I spent every weekend at The Web despite rain and typical muggy conditions, and in late October, after many days of effort and close to 20 falls, I sent Wheelin N’ Dealin (5.13c R, 115′).

This route is the hardest all-gear protected route in Adirondack State Park and exemplifies the potential that exists there. If a five-star, all-gear route can be found at the most popular cliff in a park that has more than 240 crags and 6 million acres, the potential for more such routes speaks for itself.

Because of its remote location and enormous size, the ‘Dacks may never be as popular as Joshua Tree or Eldorado Canyon. But perhaps that’s the charm of it. Its moon-like anorthosite will give many more generations of climbers genuine adventure, cliffs to explore, a place to get lost.