On April 27, climbers David Goettler and Ueli Steck reported finding the bodies of Alex Lowe and David Bridges on Shishapangma in Tibet, according to a statement by the Alex Lowe Charitable Foundation. More than sixteen years earlier, on October 5, 1999, Lowe and Bridges perished in an avalanche while on a ski expedition with Conrad Anker, Mark Holbrook, Kris Erickson, the late Hans Saari and Andrew McLean.

Here, McLean shares his reflections on the 1999 expedition, the avalanche that killed Lowe and Bridges and the void left by their passing. This article is a joint project of Alpinist.com and BackcountryMagazine.com –The Editors

October 5, 1999, was a sad day for the mountaineering community as we lost two of the biggest enthusiasts, Alex Lowe and David Bridges. Rarely a day has gone by since then that I haven’t thought of Alex, in part because I was the expedition leader and witnessed the whole accident, but also because Alex was such a good friend. I’ve lucked into many fantastic mentors over my lifetime, but Alex was in a league by himself, and not just for me, but for an entire generation of mountaineers.

The trip began innocently and ignorantly enough–after skiing Denali a few years earlier, Mark Holbrook and I decided the next logical step would be to ski something in the Himalaya. The initial research for the trip began and ended when I met Todd Bibler while browsing the book selection at the Black Diamond retail store during our lunch hour. I told him I was interested in skiing an 8000-meter peak. Without hesitation, Todd pulled out a copy of Over the Himalaya by Koichiro Ohmori, flipped it open to a spread photo of the southwest side of Shishapangma and said, “That’s the line you want to ski.” He wasn’t kidding–it was the tallest peak in the photo, and it had a splitter couloir running right off the top. Case closed. Although I had no idea even how to pronounce the name, I’d soon remember it by the handy pneumonic of “Shush and Pay More.”

![shish1 David Bridges (left), Conrad Anker (middle) and Alex Lowe sorting gear on a rooftop in Kathmandu before the 1999 Shishapangma trip. [Photo] Andrew McLean](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/shish1.jpg)

I didn’t know anything about organizing a Himalayan expedition, but I did know Alex Lowe, so I drove up to Bozeman for a weekend of climbing and advice. After going over the project, I told Alex that I was planning to put together a fundraising proposal for the trip to which he replied, “Feel free to put my name on it as a team member. I may not go, but it might help.”

This turned out to be an understatement, as we’d soon win a Polartec grant, pick up sponsorship from MountainZone.com and hit the jackpot with massive funding from The North Face in return for making a movie. Suddenly our little team of three skiers (Ptor Spricenieks was originally going) had turned into a group of nine with plots, subplots and storylines. David Bridges was the assigned high-altitude cameraman, and the main plot was that an 8000-meter peak had never been skied by an American. The subplot was that veteran alpinists Alex Lowe and Conrad Anker were taking newcomers Hans Saari and Kris Erickson under their wings. At one point during a conference call, the executive producer of the film suggested dropping Andrew McLean and Mark Holbrook, not even realizing we were the ones he was talking to on the phone.

All of this preparation was great and exciting, but a very subtle shift had taken place–instead of being a ski trip with a few warm-up peaks thrown in, it was now more of a climbing trip with a potential ski descent thrown in. In the end, this slight difference placed Alex, David and Conrad in the path of the avalanche.

![shish2 Base camp with Shishapangma in the background. [Photo] Andrew McLean](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/shish2.jpg)

Getting from Kathmandu to base camp went fairly well, aside from my bout with pulmonary edema. After pumping out a big day of vertical gain to make it to base camp, I could feel fluid sloshing around in my lungs when I endlessly coughed, and I immediately decided to head down. My plan was to return to Nylam on my own, but Alex quickly packed up and joined me. The next day Kris Erickson also descended to Nylam, where we both dried out our lungs before heading back up at a slower pace, eventually rejoining the group at base camp.

After we spent a night at our luxurious camp, October 5, 1999, dawned clear and sunny, and we decided to do some recon in the name of acclimatization. Base camp was high (about 14,000′), but still a long way from snowline, so I started out with a light daypack and hiking shoes. Alex, David and Conrad went to look at a peak off to the climber’s right, while Mark, Hans, Kris and I went straight up a glacial moraine valley to get a look at the bottom of our ski line.

![shish3 Anker drinking coffee at the Shishapangma base camp. [Photo] Andrew McLean](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/shish3.jpg)

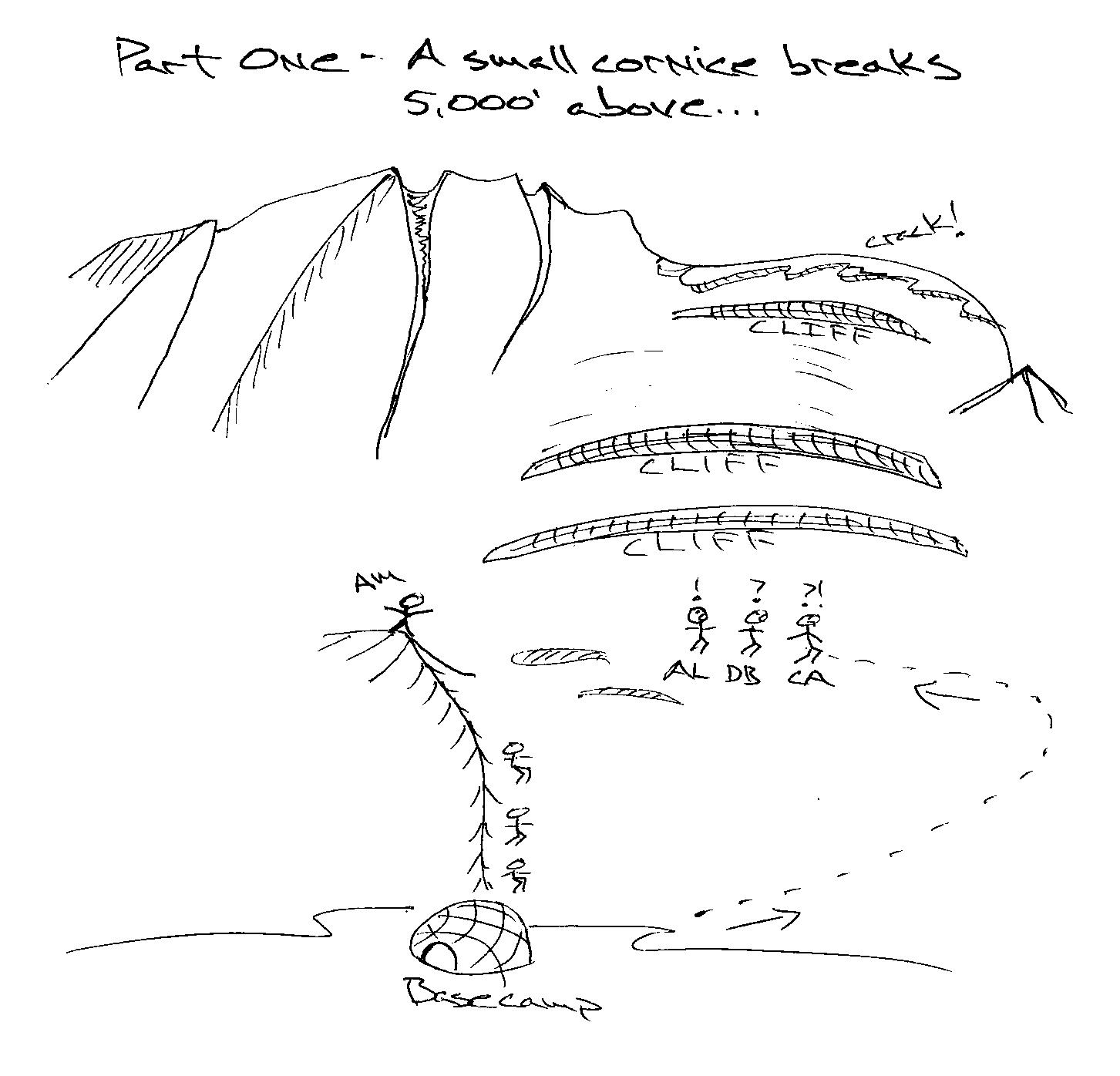

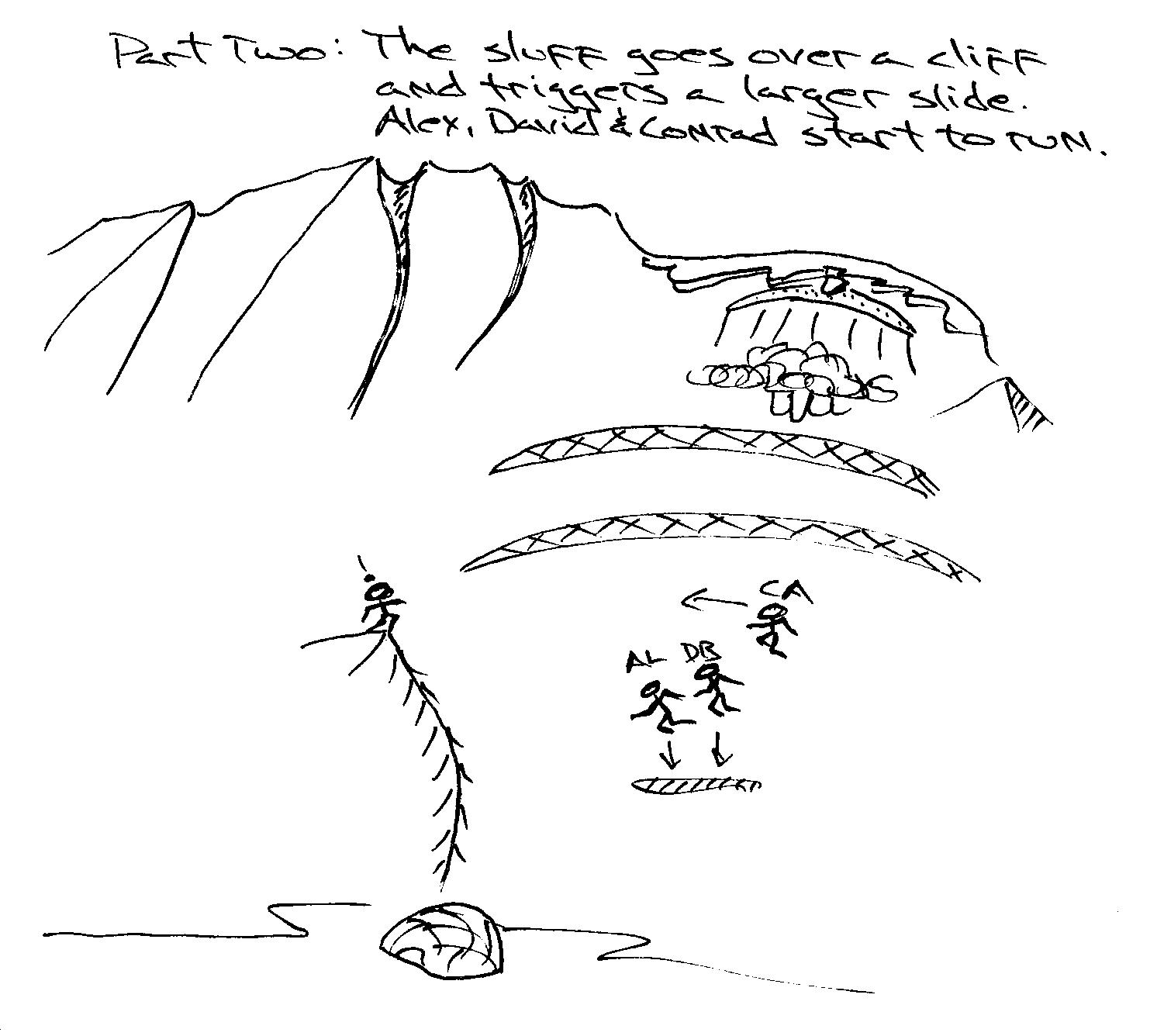

The two groups were apart for most of the day, but in the early afternoon, I had made it to the top of the moraine and could look across roughly half a mile and see Alex, David and Conrad working their way toward me on a low-angle glacier. We were separated by a few crevasses, but after some yelling, we saw each other, and I was thinking about how to navigate the cracks to meet up with them when we heard the crack of an avalanche starting high above us.

Avalanches are common in the mountains, and at first, this one was nothing to be overly concerned about as it was small and far away. I watched the trio on the glacier while they looked up at the small slide above them, probably trying to decide if it was anything to worry about, and if so, which way to move to avoid it.

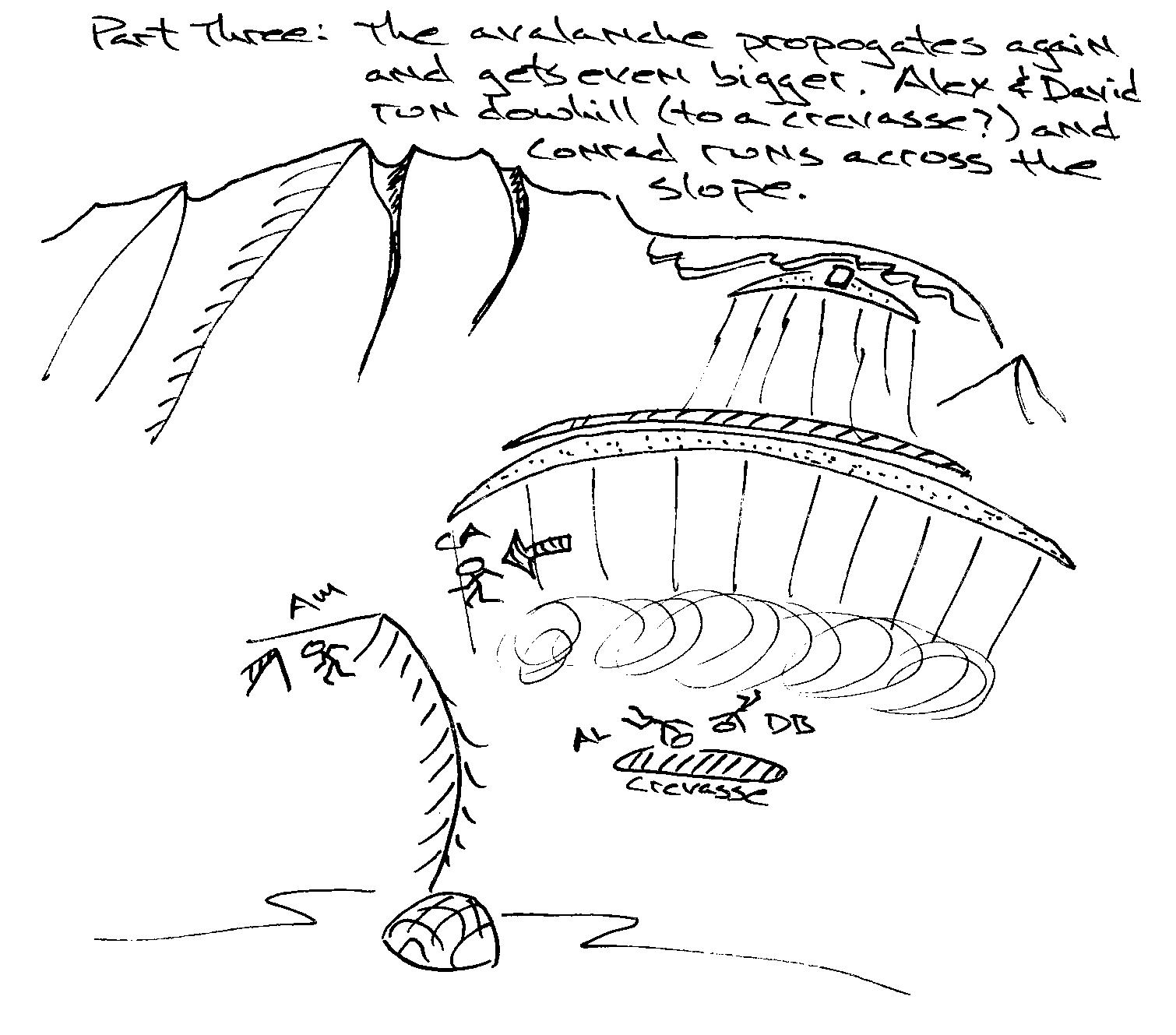

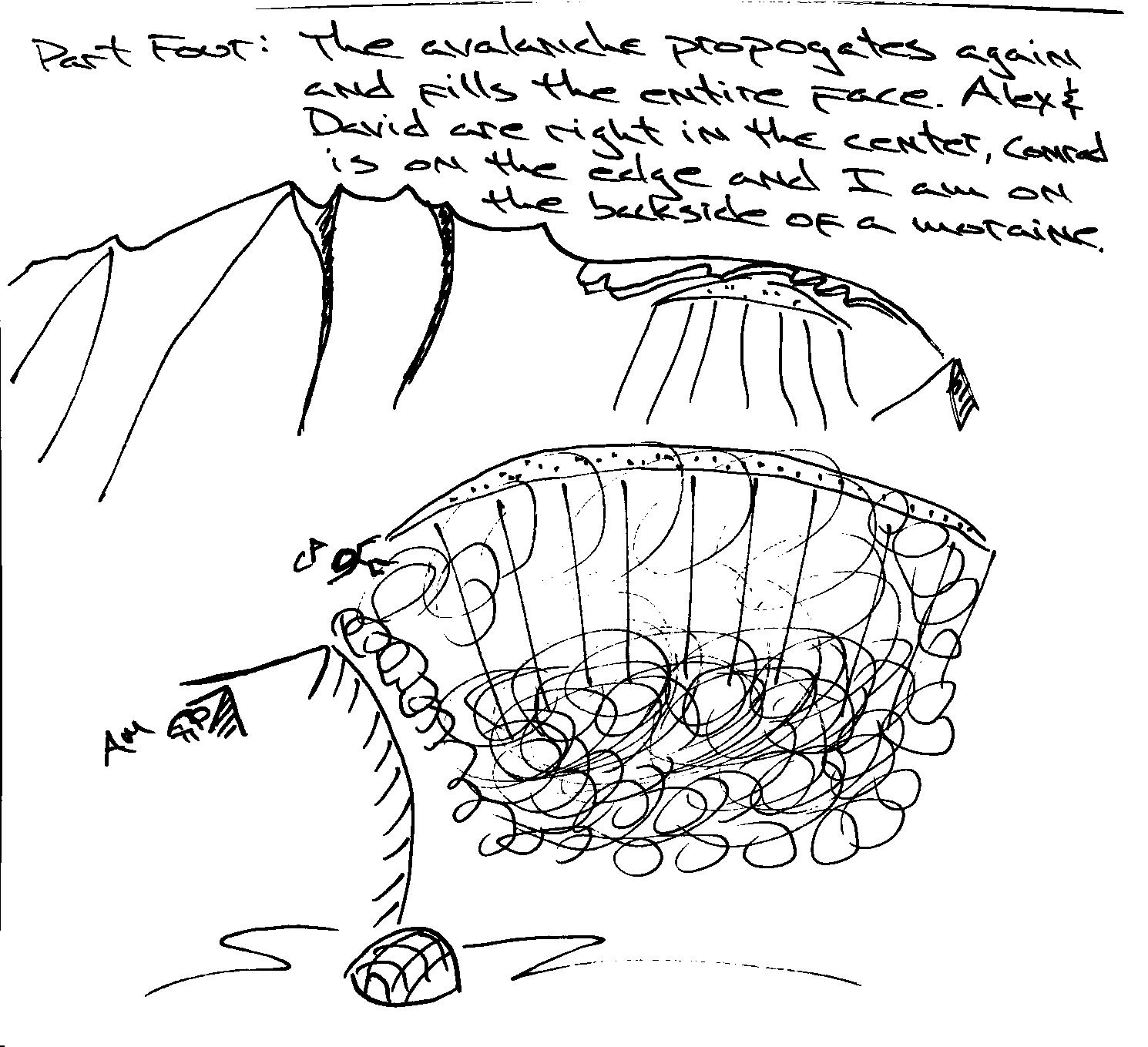

In a rapidly developing sequence that progressed from caution to alarm to full panic, the small cornice break went over a series of cliff bands, and then propagated larger and larger avalanches until suddenly a giant avalanche consumed the entire valley–a huge snow cloud with a fast-moving tongue coming out at the bottom and three very small-looking figures running to get out of the way.

At this point it occurred to me that I was going to get hit as well, so with limited options, I turned from my perch on the moraine ridge, ran down the back side about 50 feet and found a corner of rock where I could hide. The last thing I saw before I left the ridge was the valley exploding in snow behind me. I knew it was just a matter of seconds before I got hit as well. Burying my head and taking deep breaths, I tried to remain calm. Seconds later, the force of the air blast smashed my face into the rock hard enough to break my goggles and fill everything with snow. After a few seconds it all dissipated, and I was ecstatic to find myself still alive.

As I ran to the top of the moraine, I saw a tall figure staggering down the open slope, which was now completely filled in and free of crevasses. Assuming it was Alex, as he was invincible, I walked closer. I soon realized the figure was a very beat-up and bloodied Conrad, who just said, “They’re gone. Alex and David are gone.”

When I took a look at the size and volume of the debris, I knew his statement was obviously true–the slope had been blasted as if it were hit by a nuclear warhead, and it was a miracle that Conrad was still standing. We did a short search that evening and the following day, but we never found a trace of Alex or David.

![shish4 Mark Holbrook (left) and Hans Saari dozing at the advanced base camp. The slopes where Lowe and Bridges were killed are the large, open glaciers and the avalanche came down from the peaks in the clouds. [Photo] Andrew McLean](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/shish4.jpg)

The first night was perhaps the worst as I kept expecting Alex and David to come bursting into the tent with a wild story of survival, which never happened. On the second night, I still had a thread of hope, but when morning came around, even that remnant was extinguished. Alex and David weren’t coming back alive.

By the time the trip ended, I was over the Himalaya, I thought it was a beautiful place, and I loved the travel and cultural aspects, but the odds of skiing off the summit of an 8000-meter peak are low, and even then, the snow conditions are likely to be firm, to say the least. Hats off to those who have done it, but I turned my attention to lower objectives with better skiing options, and I have not been back to the Himalaya since.

![shish5 The southwest face of Shishapangma. The summit has a lenticular cloud on it, and the slopes that avalanched are the ones in the shade off to the right with the cliff bands. McLean was standing on top of the moraine looking down and into the hidden valley on the other side. [Photo] Andrew McLean](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/shish5.jpg)

After the accident, there was always the question of why nobody was wearing avalanche transceivers, especially as this was a ski trip. Although we had them back at base camp, we had started out the day with only a recon hike in mind, and we didn’t bring skis or intend to get into avalanche terrain. Alex, David and Conrad were on a very low-angle slope when the avalanche hit them, and it was more a case of being in the wrong spot at the wrong time. Fifteen minutes one way or the other probably would have had a much different outcome. It was such a huge avalanche that beacons might have helped with body recovery but wouldn’t have made the slide survivable.

Even now, more than 16 years later, it is a rare day that I don’t think of Alex. As a mutual friend said at Alex’s memorial, “We are the lucky ones; we knew him. I feel sorry for those who never will.” Anyone who spent even an afternoon with Alex in the mountains came away with the feeling that they were his best friend, a connection that was genuine on Alex’s part. He loved the mountains, but even more so, he loved turning other people on to the mountains. Although most of our adventures together took place in the mountains, what I miss most about him was his friendly presence. Alex was a voracious reader who also turned me on to many excellent books, and for the first few months after his death, I’d catch myself finishing a book and thinking Alex is going to love this one, only to realize he wasn’t.

![shish6 The glacier where Lowe and Bridges were caught by the avalanche after it passed. [Photo] Andrew McLean](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/shish6.jpg)

Alex and David’s bodies were recently discovered by Ueli Steck, an event that came as a surprise as I didn’t think they’d be found in my lifetime, if ever. They could have been blown farther down the mountain than I’d ever imagined by the force of the avalanche, or perhaps they were buried in the faster-moving, upper layers of snow. Or perhaps the glacier has melted farther up than I would have imagined. Or maybe Ueli found them in the middle of the glacier. I don’t really know, and unless they can be brought back to life, I’m not overly curious.

On an earlier climb with Alex on Mt. Conness in California, we came across a memorial plaque bolted to a rock in honor of a fallen climber. Thinking it was a beautiful spot for a memorial, I asked Alex where he’d want a memorial, under the assumption that he had some especially cool, beautiful or unique place in mind. Instead, he said, “I just want to be somewhere in a beautiful mountain setting and don’t need a plaque.”

In that regard, Alex got his wish as the south side of Shishapangma definitely qualifies as beautiful. So it was a bit of mixed emotions to hear that their bodies had been found.

![shish7 Kent Harvey (blue) examines Conrad Anker’s head wounds while Mark Holbrook looks on. [Photo] Andrew McLean](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/shish7.jpg)

For me, closure came on the second night after the avalanche when I realized they were not coming back. That’s not to say I was in any way over it, but I also didn’t have any questions about what had happened; it wasn’t like they had disappeared into the desert or a war and never been heard from again. Over the intervening 16 years, I’ve had a couple of very vivid dreams in which Alex somehow miraculously resurfaces and folds right back into his old life. The dream is exciting at first, but it gradually gives way to the pervasive question, “Where have you been all this time…?” He usually just smiles, which is right about the time I wake up.

Unfortunately, Alex and David are not the only two friends of mine who have died in the mountains over the last few decades. I’m superstitious about removing any of my deceased friends from my phone or email list and, after a while, it has become a good reality check. Skiing and climbing can deliver the highest highs, but it comes at a price: these sports are definitely dangerous. Whenever a friend or acquaintance dies in the mountains, a common refrain is that they died doing what they loved, and they could have just as easily been hit by a bus. In response to this statement, my savvy wife has pointed out, “How many friends do you know who have been killed by a bus?” Exactly zero.

![shish8 Anker walking back from base camp after the avalanche. [Photo] Andrew McLean](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/shish8.jpg)

From my own experience, I know that when I’m in the moment and having the time of my life with a close group of friends in an incredible location, the adventure doesn’t seem that dangerous. Likewise, when I’ve pulled off a big mountaineering challenge, I feel as though I’ve experienced the stuff of dreams: life seems so much more exciting and vibrant. I can fully relate whenever extreme athletes say, “I don’t have a death wish, I have a life wish.” Nothing makes a person feel more alive than a front-row seat at the edge, but spending too much time there can warp reality. As Chris McNamara said in his documentary film about why he gave up BASE jumping, “If you have the skills to BASE jump, you have the skills to do anything.” The secret is finding joy and meaning in nonlethal challenges. Contrary to an extreme athlete’s belief, spending a day in a cubical will not kill you.

After losing so many friends, I always wince when I hear their names being used as words of encouragement–Trevor would do it, Alex would do it, Shane would do it. I don’t know. I’ve never actually conversed with the deceased, but I’m guessing that most of them, from the other side of the grave, would say dying is not worth it. Chill out, wait for perfect conditions, come back tomorrow, enjoy time with your family, expand your horizons, pet a dog or simply enjoy the moment. Risking your life is obviously a personal choice, but it has real, long-lasting consequences for those who are left behind.

![shish9 A stone memorial bench to Lowe and Bridges at the Shishapangma base camp. [Photo] Andrew McLean](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/shish9.jpg)

Although Alex and David are gone, their presence lives on in anybody who climbs, skis or enjoys the mountains. Finding their bodies brings back memories of the day they died, but it also reminds us that their spirit will always live on.