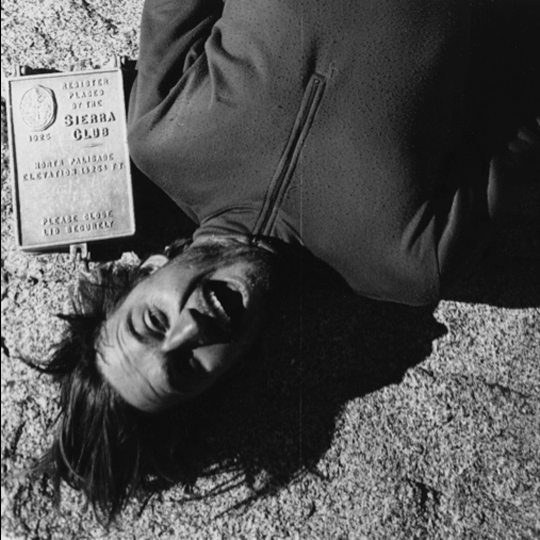

I blame Steve Porcella for the pain:

Sixty-five Sierra routes that first summer; about a dozen the next, a fifth of them first ascents. Brutal-as-hell approaches with seventy-pound packs, decrepit knees and bad footwear.

I blame Steve, but really, he and I were just the syringe plungers, and the Sierra Nevada was the heroin.

I met Steve in the winter of 1989, in Solano Beach, San Diego County. I was twenty-four, living in LA and working in the film industry. I’d just rumbled across the border (rumble being both a vehicular and gastrointestinal reference) after a low-budget Mexican volcano-bagging trip. I’d lived for a month on only $300, dossing in beachside construction sites and sleeping in bus aisles. My friend Paul Fehlau had picked me up at the trolley stop. His housemates were having a party. There were no available cups, so I filled a saucepan with beer.

Starving, I rooted through Paul’s barren cabinets and found some falafel mix. As I stirred it in with the beer, a lanky blond bloke drifted by. He took note of the saucepan and the falafel mix, and he laughed. His name was Steve Porcella–he later earned the nickname “Porch Dog,” based on our shortening of his Italian surname.

“You a climber?” he asked.

“How could you tell?”

“Your face is sunburned like toast, and I’m guessing you’ve been on a glacier for a month. And you seem to have no understanding of skin care.” Steve had grown up in Modesto in the shadow of the Sierra; his father was Royal Robbins’ doctor. One of Steve’s first climbs had been a new route on Shepherd Crest with the great man himself. Now Steve was studying biology or something useful, unlike me; I was just trying to climb. Eight years my senior, he later told me he was thinking, “This Padawan has promise. Either that or he’s gonna get light-sabered through the twins.

That night, we swapped climbing stories so intensely that we forgot the mosh pit-style party and the beautiful, eager women surrounding us. We were doomed.

Impressed with each other’s ability to bullshit, we hit Mt. Woodson the next day and then planned a summer of Sierra climbing. Many rightfully consider the Sierra the finest mountain range on earth. Galen Rowell always told me so. My mentor Dave Brower knew it. Dave Wilson knows it. White, white granite that is solid and gritty. Nearly always perfect weather. No other climbers, because you have to hike. You can scope a new line and come back twenty years later, and it’ll still be untouched. The sky will be pure cobalt blue, and you’ll be bleeding at the wrist as soon as you crank that first jam and realize you misapplied your tape.

In late March 1989, I finished a demoralizing, stress-filled job as an electrician on a Hollywood movie. Steve was maneuvering through his graduate career, with seemingly random breaks. We were both ready to escape the teeming humanity of Southern Calamity (aka: Southern California).

Our first trips included a quick jaunt up Mt. Tyndall, unroped. We launched up the north rib, first done by Clarence King and Richard Cotter in 1864–a simple climb under normal (i.e., good) conditions, but a snowstorm moved in as Steve and I wove along ledges on steep granite. I slipped down a big slab, bouncing for several hundred feet, until my axe pick caught on an edge and jolted me to a stop. The fall hurt like hell, but I was young and resilient. Back at camp, with only my Walmart sleeping bag and a tarpaulin, I became hypothermic and had to be put in a hot bath in a motel room. I didn’t own a stitch of proper outdoor clothing other than hand-me-downs and thrift-store finds–all junk.

The next outing, in April, was roughly the same–the iced-up east face of Whitney. We suffered through a summit bivouac and descended John Muir’s Mountaineers Route, delirious, the next day. Even then, I could see that Steve was a master climber–and an adult. I was still a kid, raw muscle and zero brain, just trying to follow his lead. One morning that year in a town park in Bishop, I was drinking my usual twenty cups of tea (I’m a Commonwealther) laced with sugar until I became amped and impatient. Steve recognized my angst and turned it into movement. We were on Split Mountain by the afternoon. We made the perfect team.

In early July, Steve and I hiked into Dusy Basin, on the west side of the Palisades, with enough food for ten days. We soon learned that the “back side”–always an inspiration for guys like us–is the “big bith-ness,” as one of John Waters’ characters in Desperate Living said while donning underpants.

We gazed upon massive walls, buttresses and, well, yep, innocuous gullies. Before us soared 1,800 feet of glorious rock. Sweeping architectures of granite and diorite decorated with delicate doilies of quartz and other stones. Crack systems that leap up, then run out and sometimes–often–leave you stranded, scared and wobbling. Lines that jump into the sky. None of this easy snow-climbing U-Notch and V-Notch semi-alpine crap that makes LA climbers think they’re ready for K2.

Glorious big bith-ness.

Several of the routes we did were variations of existing climbs and some just mangled combinations of fourth-class gullies loaded with the usual alpine smorgasbord of water-washed slabs and perched, hanging blocks. The guidebook author R.J. Secor says that we probably made a lot of first ascents of those gullies–but really, who cares? We were covering four to six miles every day for nearly three months, generally 4,000 to 7,000 feet in elevation gain and loss. We pounded out lines on all the Palisades peaks and a few others. It was go-go-go, a climbing-based methamphetamine binge. Were we mental? Maybe. Or maybe it was just a shitty society pushing us–because a lot of society is pretty awful. Here, there were no bosses, no crazy girlfriends, no bullshit. Just running around the mountains: pure, perfect freedom, a high-voltage current that drowns out throbbing feet, burning quads and clicking knees.

Looking back at my notes, now, from my house in Colorado, I see that our “rest days” (when we emerged every two weeks or so to buy lentils and rice) were spent climbing things like the East Buttress of Middle Cathedral and the Regular Route of Fairview Dome. I wish I had that kind of energy now. Hell, look at those dirty dishes in the sink and that hole that needs patching in the drywall. I’d rather be back in Dusy Basin. I think every reader would rather be back there. Drywall holes and dishes are not important.

A year later, after exchanging letters with Steve Roper and Galen Rowell, we knew there was more. Galen and Dave Wilson had cut a track up the biggest wall on the west face of North Pal, but human hands had yet to touch the two massive buttresses to the north and south. Before we climbed the right-hander, I thought about the time Steve had made out his will. In his notebook, he wrote, “I leave all of my crap to….” If memory serves, it wasn’t me. Steve didn’t have many things. I was just envious of his truck.

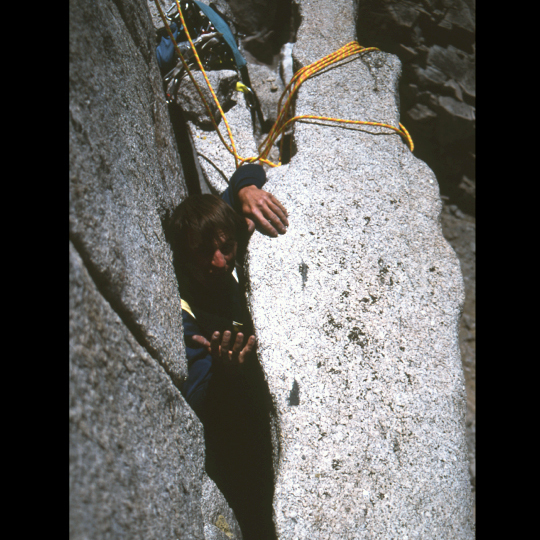

We cranked out the two big butts. I’d been dirtbagging and sport climbing like a madman, doing 300 pull-ups a day. But the start–the crux–of the Southwest Buttress was an overhanging offwidth. I wiggled up twenty feet and fell out. Steve wiggled up another twenty feet and fell out. Then I wiggled up some more, pushing our sole no. 4 Friend far back in the crack. Soon I was on a ledge. I think Steve was wondering why I’d picked that line. I’d started asking myself the same thing, but it was one of three awful-looking cracks that appeared about the same–gotta follow a good line, right? Atop that first pitch, the rope fell down behind a flake, and we spent an hour fishing it out. We continued another 1,800 feet, following a tiny crack system with small, incut edges and stances every twenty to thirty feet. It was the hardest free route at the time on a California Fourteener, though, of course, Kevin Steele and his buddies came by a year or so later and blew that all out of the water on Keeler Needle. Thanks, mate.

A few days later we took on the other buttress, on Starlight, a lovely, flying piece of rock that dragged your thoughts and ideas skyward. There were several big, flat ledges, but also moments of “Holy shit, how do I protect this?” I look at photos now, and I’m astonished it hadn’t been touched: a wonderful, cracking line, a piece of Sierra rock splitting the firmament. Stone so gentle you could wash your hands with it. No runout scariness; no “Where-are-we-going-next?” Steve and I went up and up and up, digging every moment, every stem, every jam–every thing. The sky was azure and the wind was kind all the way to the top.

I’ve since climbed with a few big names, and while those partners were all great fun, none, ultimately, was more important than Steve. He never asked more of me than I could deliver, and he always delivered more than I could ask. Forget the stone. A good partner, an understanding and wise partner, is everything. That’s the ticket. Buy that ticket; it’s the best investment you’ll make. And of the best routes I’ve climbed–there must be a mathematical equation there somewhere–nothing, to date, has been as meaningful as those Palisades climbs. And especially those on the back side.

So cherish the back side. It’s a special part of the world.

This week, we’re publishing the four essays from the Palisades Mountain Profile, including Joan Jensen’s thoughts on “The Nature of Memory” and Cam Burns’s retelling of his “backside” adventures with Steve Porcella. Daniel Arnold tracks the histories of the Palisades’ early pioneers while Peter Croft does what Peter Croft does best. We’re also publishing a bonus essay by Steve Porcella about his quest for the “remote, barren, trailless, treeless, oxygenless and peopleless,” where he finds out what it is to really know a mountain range. CLICK HERE to read the essays as they progressively become available, or purchase a copy of the entire issue in our online store.–Ed.