[This story originally appeared in Alpinist 71, which is now available on some newsstands and in our online store. Only a small fraction of our many long-form stories from the print edition are ever uploaded to Alpinist.com. Be sure to pick up Alpinist 71 for all the goodness!–Ed.]

![ed-roberson-1 Ed Roberson on Mt. Washington (Agiocochook), New Hampshire, date unknown. [Photo] Courtesy Frank Daugherty](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/ed-roberson-1.jpg)

AUGUST 7, 1963: Thick storm clouds rolled in below the team of three climbers; soon, the silver-metallic scent of snow was in the air. Ed Roberson stood atop the summit of the Nevado Jangyaraju III (5450m) in the Peruvian Andes, looking down at the jagged grey bowl below. Shortly before, his teammate had offered Roberson the final lead to the apex. This moment will reverberate throughout his life’s work: the intimate camaraderie between climbers and the formidable natural beauty that charges and expands the mind.

Ed Roberson was born in 1939 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. As a young man in the 1960s, Roberson fed his self-described “burgeoning curiosity for the world” by embracing what he explains as the Black Bohemian lifestyle. As a college student at the University of Pittsburgh, Roberson traveled to Alaska for his first field expedition. He was there to conduct limnology research (the study of freshwater environments like lakes and streams), but it was during that trip that he discovered his affinity for wild landscapes. Roberson started taking notes on his observations in the field around him.

In 1963 he joined his first mountaineering expedition to South America. In the 1960s, outdoor culture was in the midst of the “rucksack revolution.” Meanwhile, the Black Arts Movement encouraged the publication of writing by Black authors that was political and activism-based. Roberson sees his life and work during that time as a response to the call for wildness, for freedom of expression of the self. “Climbing wasn’t attainment, a grand goal, an achievement, nor was it self-improvement or proof of betterment. It was having fun, getting up high enough to see everything,” he says. Today, he reflects, “Maybe I did think that I was getting to a place where I could have a freer, less segregated expression of being Black out in the wild, of being myself.”

Roberson’s field notes would later become the foundation for his prize-winning poetry, which centers around nature and the complicated interactions human beings have with the earth. He published his first poetry collection, When Thy King Is a Boy, in 1970. Since then he has been awarded the Iowa Poetry Prize for Voices Cast Out to Talk Us In, a 1998 National Poetry Series award for Atmosphere Conditions and the 2020 Jackson Poetry Prize. Close field observations and innovative lines make up Roberson’s poetic aesthetic. “I’m not creating a new language,” he says. “I’m just trying to un-White-Out the one we’ve got.”

The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

![ed-roberson-2 Roberson with the Explorers Club of Pittsburgh's flag atop Nevado Jangyaraju III. [Photo] Larry Wolfe collection](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/ed-roberson-2.jpg)

Sarah Audsley: When did you first become interested in climbing? Did you begin writing around the same time?

Ed Roberson: As an undergraduate student, I went to Alaska to conduct limnology research. “What’s this? What’s that?” were questions I asked. I had never seen or experienced a landscape like it. My eyes picked out the movement of tiny specks high on the mountain, and since they were not making movements previously known to me (they didn’t look like sheep or goats), I asked, “What’s that?” The answer came: climbers. Upon returning to Pittsburgh, I immediately enrolled in my college’s extra-curricular climbing club and formed a small group of fellow climbers made up of my roommates and lab partners. The poems and writing came later.

Audsley: How did you become involved with the Explorers Club of Pittsburgh (ECP)? And can you describe what it was like to be a member of this club?

Roberson: The Explorers Club of Pittsburgh was organized by Ivan Jirak, a high school teacher and former serviceman. Club members were a combination of university students, architects, doctors and engineers. We’d go out to the local rock sites on weekends when everyone could get free. We learned to climb, belay, rappel, tend rope and tie knots, as well as general camping procedures and safety systems like crevasse rescue.

Audsley: When you were climbing–in the 1960s and 70s–what was your standard equipment? What was in your pack?

Roberson: Our manuals were mimeographed sheets. REI was in someone’s garage somewhere. Our equipment was mostly handed down, passed around and bought out of any convenient Army-Navy store. Today, I am surprised by the quality of the ropes, carabiners, camming devices and other tools that are available to climbers.

Audsley: In 1963, at twenty-three years old, you went on your first major international mountaineering expedition. I read about your climbs in the central Cordillera Blanca that year in a trip report from the ECP. Ivan Jirak had organized two small teams with the goal of making several first ascents of unclimbed peaks in Peru. During that trip, your team also made the second ascent of a peak that the 1964 AAJ trip report refers to as Bolivar (the peak is known today as Nevado Jangyaraju III). Can you tell me more about that experience?

Roberson: Before I got to Peru, one climbing team had already begun their leg of the expedition: Ivan, the expedition leader, team doctor Duane “Bud” Ewers and climbers Sam Colbeck and Kent Heathersaw. [They’d made the first ascent of Nevado Jangyaraju II (5630m) and planned to climb Nevado Jangyaraju I (5675m).] My teammates Larry Wolfe and Hugh Bloom and I traveled from Lima to the small town of Huaraz, the main access point for all expeditions to that region of the Andes. We were joining the group as a separate summit team for an attempt on the peak Bolivar. When we arrived in Huaraz, we heard there had been an accident. We had no idea what had happened.

Ivan came down to meet us and explained what was going on: no one had been killed, but Kent had developed pulmonary edema, and the team was working quickly to get him down the mountain. They had bivouacked twice above base camp, and Bud had stayed to care for him. We were supposed to remain in Huaraz for a day to acclimatize, but Ivan asked us to ascend to 15,000 feet as fast as possible to help facilitate a rapid descent. So the very next day we were gone, moving with packhorses up to base camp at the top of the moraine lake.

![ed-roberson-3 A map from the Explorers Club of Pittsburgh's report on their 1963 El Sangay Expedition. [Photo] Ed Roberson collection](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/ed-roberson-3.jpg)

By the time we were at the top of the lake, the rescue team had just crested the icefall of the glacier. We waited until the team traversed and met us. Kent was packaged up in the litter, what Ivan jokingly used to call “the casket.” It was slow going, but we got him safely down, and he made it to the hospital. [Kent ended up losing several toes to frostbite.] Bud stayed with him in the hospital. Ivan stayed with us to help facilitate another summit attempt.

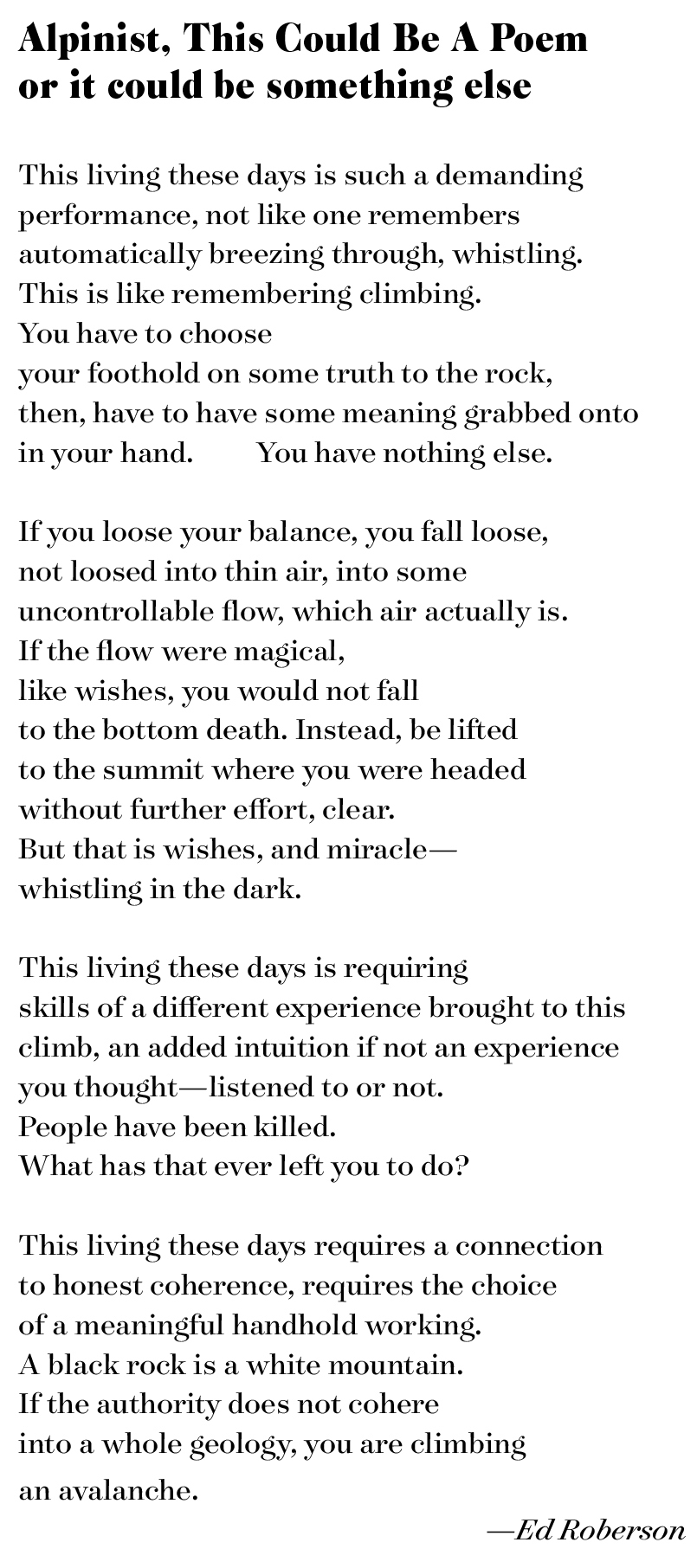

That’s how Larry, Hugh and I were able to summit Bolivar. What I remember most vividly about that day was when we were just below the top and Larry said to me, “Here, you lead.” I was just a kid with these old guys, and they sent me up there. Larry let me have a go! He offered me the final lead, right at the top. It was absolutely amazing. Larry and I remained friends for decades afterward, and before his death I was able to tell him how much that summit meant to me.

I remember arriving on the summit and realizing that there was a blizzard coming in. We couldn’t see as far as we were hoping to, just the tops of clouds. We quickly took our pictures and then headed on down. The last bit of the descent was under falling snow, but it wasn’t scary. Ivan was waiting back at high camp and was worried about us, but we knew where we were and felt confident we’d make it back to camp without incident. I remember pulling into camp and going straight to sleep.

Audsley: The expedition also traveled to Ecuador, to the eastern edge of the Andean Cordillera and the base of the upper Amazon jungle. The goal was to try a new route up the glaciated volcano of El Sangay (5286m). Can you describe this portion of the expedition?

Roberson: On the way to El Sangay, a small tri-motor plane flew us from the town of Shell Mera to Macas. We were behind on our itinerary and so some of the team members left to go back to Pittsburgh. Ivan still wanted a team to attempt El Sangay anyhow. Bud, the doctor who cared for Kent, hadn’t had a chance to do any climbing so he was anxious to climb. As a kid at the time, I was like, “Me too! Me too!” So Bud and I took off, just the two of us, into the jungle–I’m so glad we did.

Three or four people from the local Indigenous group, the Jivaro, started out with us as guides, but when we woke up the next morning they were gone. We didn’t know what to do. We were still close enough to town when another Jivaro person stopped by.

He said he knew the way and could arrange a team of his friends. He took us as close as we got to El Sangay.

Audsley: I understand that you had to use machetes to move through the difficult jungle terrain, and that the Rio Volcan flooded that year. Can you describe this part of the expedition?

Roberson: I remember arriving at the point where the Rio Volcan goes through a very narrow canyon. We waded through it to the other side and guessed that we were at about 13,000 feet. We could smell the volcano from a couple vents. At this point, we were still not above tree line.

Of course, being curious, I wanted to see a volcano vent. So I climbed up to look, and when I turned around I saw that the water near Bud was very turbulent, like maybe it was rising. So we decided that we had better get the hell out of there. Descent meant making our way through the canyon. Just as we got to the mouth of it, where the river opens up, a storm started and the sky turned black.

We found a rock, crawled up on it and tried to sleep. I had a sleeping bag that we offered to the two Jivaro guides. Bud and I were dripping wet, but we crawled inside a sleeping bag, naked, to keep ourselves warm. We woke up the next morning and had lost stuff from our packs from wading in the water. I lost my camera and all my notes from Peru.

The next day, our guides found fish in the puddles left by the flood. We ate them raw. I had never seen a fish that had [scales] like that. Years later, I would be working the night shift at the aquarium, in the South American division, when I saw that exact same fish I had eaten to keep myself alive in the Amazon jungle. I was really nice to that fish from then on! Bud and I never made it to the summit of El Sangay, but we did come back with stories. Even though I climbed for a short period of time, those experiences lived with me; I lived with them.

Audsley: Throughout much of the history of climbing in the West, dominant narratives of mountaineering have been written by white men, and climbing has been seen as a mostly white, male-dominated sport. Could you share a bit about your experience as a Black climber in the 1960s and the 1970s?

Roberson: What was it like being around white people?–is what you are asking when you want to know what participating in a historically white-male dominated sport was like. As in a lot of situations such as that, people don’t see you as really there, at least there for any reason or any length of time. I’m an anomaly to be experienced, not really a person. Being Black in a white, male-dominated sport I would say was like being in much else of the world. Climbing was simply a little more focused on the necessity: if a climber could trust my skills, he could trust me.

Audsley: Are there any specific examples from your expeditions you’d like to share?

Roberson: When we were preparing to return to the States after climbing in South America, some of the Ecuadorians–who were surprised there were any Africans left in the United States (they thought we had all been exterminated)–began to tell me not to go back home, that the Americans would kill me. They asked me to stay and live with them. One of my team members achingly found himself agreeing with them and offered me the rest of his money as a stake. That really shook me.

Another example: one team member from California got upset when he realized two of the little Indigenous kids were rubbing my skin to see if the black came off. It was amusing to me. One of our Black jokes is that it don’t. It does, but not where you can see it. It’s more where you can feel it. I was surprised he could feel them rubbing my skin, as a participant in American racial history, rather than as an amusing, naive innocent encounter.

Audsley: In your poetry, your ability to both observe the natural world around you and to craft a speaker who is not completely removed from, but also participating in the world, is striking. How did you begin writing poems?

Roberson: I never had any formal training in poetry, but I have always hoped for a very large inclusiveness. Writing, for me, began as field notes and observations first before the emotional impulse. I didn’t think of it as taking notes, necessarily. I hadn’t ever thought of being a writer. I simply wanted to remember things and I’d write them down when I had a moment [on an expedition or research trip]. I began to think that maybe they could be poems, but I didn’t start writing them down that way.

Audsley: Can you describe your writing philosophy or your approach to writing about nature? Literary critics often define your poetry as distinctly contributing to ecopoetics, a lineage that offers thinking on ecology and human impacts on the environment.

Roberson: As I wrote in an essay for the anthology Black Nature, “Ever since Alaska, I’ve been ‘doing nature’; taking down the data in my writing, not only of the present natural world but the data on myself in that world, on myself as just another one of nature’s innumerable components. This self-conscious attention to being in balance–careful, to being a part of nature, not separate as its master or its crown–was to become one of the basic positions of my ecopoetics. My orderly handling of the nature poem came from my feel for basic scientific observation and technique, not the order of a metaphysical imperative.”

Audsley: How do you feel about the world, now, through the lens of your climbing days? Are there any lessons about living in the world that you gleaned from those experiences?

Roberson: I always have had a respect for how like people were…. One example of learning from my climbing: I remember, in Ecuador, we were walking in the jungle. The Jivaro guide in front of me was pulling off these red berries, crushing them in his hands and painting them across his face. I didn’t know what he was doing. I was watching him and becoming very suspicious, until he turned around and offered me the berries, gesturing for me to put them on my face. It was a bug repellent! These types of experiences really widen your perspectives on people, who they are and how they live.

Audsley: When did you shift away from climbing and focus on your academic career?

Roberson: I stopped climbing decades ago, after the last South American expedition. I got married, had a baby and settled down to my first solid teaching job. But a few years ago, when I started hearing about climbing again, I looked around and could hardly believe what I saw.

I’m from the days when to walk in with a nylon rope was equivalent to walking in with the first Apple computer, when the only other computer you knew of was a Commodore. Writers see this shift as the evolution from pencil and paper to Word docs and PDFs on electronic tablets. When I looked at the new climbers’ magazines, it was like seeing Transformers. Such gizmos and technology was undreamed-of back in my day. And the expertise in climbing skill was humbling. Now I am embarrassed to think that what I had done was rock climbing or mountain climbing. My caveat saying is always, “We were just kids hanging out in the woods, in the jungle.” It still is.

Audsley: Any last thoughts on navigating the two worlds of poetry and climbing?

Roberson: Beyond the field notes, taking down the stories is where the poems come in. I guess in this sense, the expeditions, the climbing, the adventures informed me about how to stay informed. Adventures showed me what information was. It was not what the literature said, because the field reports were only guides. It is you, we, who has to be there. I’ve been sort of taking constant notes for poems like field guide reports ever since. The poems are meant to set me up to “be there” every day. I’m eighty years old now, so I’m more likely to walk the rest of the way to the summit, rather than climb it.

![ed-roberson-4 For years, Roberson often hiked Mt. Washington (Agiocochook) on his birthday, December 26, as likely pictured here. [Photo] Courtesy Frank Daugherty](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/ed-roberson-4.jpg)

[Climbing poems by Ed Roberson that were previously published in Alpinist 58 (Summer 2017) and Alpinist 67 (Autumn 2019) can be found here. This story originally appeared in Alpinist 71, which is now available on some newsstands and in our online store. Only a small fraction of our many long-form stories from the print edition are ever uploaded to Alpinist.com. Be sure to pick up Alpinist 71 for all the goodness!–Ed.]