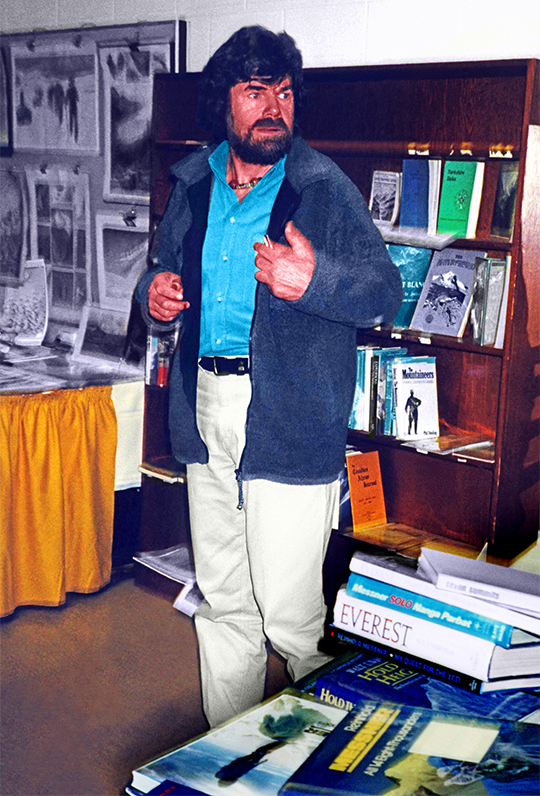

[Photo] Ed Webster

When next I encountered Messner it was during the year 2000 Mountaineering extravaganza at the Banff Mountain Film Festival in Canada, a “Who’s Who” red-carpet assembly of many of the world’s greatest climbers. I wasn’t invited; I just went.

I spotted Reinhold at an evening reception, engulfed by a gaggle of European journalists and hangers on. As I approached, he saw me, burst from the horde, hand extended, and shouted: “I put you in my Yeti book!” which we both had a good laugh about.

Later he agreed to autograph some mountaineering books, ones he’d authored, plus others–about twenty-five. His eyebrows raised when he glimpsed the pile; he’d already signed hundreds that day. I did feel maybe my timing wasn’t very good. “I’ve never understood what it is, why people like autographs so much,” Messner muttered while dutifully signing “R. Messner” as fast as was humanly possible–like his climbing.

“Wait!” I brazenly interjected. “You know we have met each other before…. Can’t you please sign some of them ‘To Ed,’ write something nice, and maybe add the date?”

“I do not have any time for that,” Reinhold stated emphatically–before backtracking and adding, “To Ed, Lhagyebo! (‘Victory to the Gods!’ in Tibetan),” and the date in several.

Then he paused. In his hand he held his partner Peter Habeler’s book about their historic 1978 First-No-Oxygen-Bottle “By Fair Means” Mt. Everest ascent. Reinhold turned Peter’s account toward me.

I’d heard Habeler and Messner experienced a falling out after their respective books on the climb were published: Reinhold’s Everest: Expedition to the Ultimate, and Peter’s Everest Impossible Victory, which was subsequently released in the United States as The Lonely Victory. How very sad, I thought. The two greatest Himalayan mountaineers in history saw their friendship crumble directly after their most noteworthy ascent.

I took a chance.

“What happened between you and Peter? I don’t understand it,” I said. I’d met Habeler once, several years earlier in Colorado. Such a likeable person, how could anyone hold a grudge against him, of all people?

“Did you read his book about our Everest climb?” Messner asked.

“Yes, I did, but honestly I didn’t see anything objectionable,” I replied.

Messner exhaled loudly. “Look what he called his book: The Lonely Victory. But I was there too!” he fumed.

“Oh, that’s just the hyped-up title his American publisher in New York gave the book,” I answered, “You know, trying to boost sales.”

“The original title that Peter gave his book, to the original English-language edition published in Britain, was Everest Impossible Victory,” I added, sticking up for Habeler.

Reinhold just shook his head, signed Peter’s book, and said, “OK, finished.”

————————————————————————

2013 stood out as a unique “Anniversary Year” in the history of Mt. Everest.

It marked the 60th anniversary of the mountain’s 1953 British first ascent.

[Press Photo] Ed Webster Collection

The 50th anniversary of the first American ascent, including Tom Hornbein and Willi Unsoeld’s ahead-of-their-time new route up Mt. Everest’s West Ridge and their first traverse of the peak, in 1963.

It also was the 30th Anniversary of the second American first ascent up Everest, the 1983 American Everest Expedition, the first to successfully ascend the mountain’s most dangerous and daunting aspect, the East or Kangshung Face, in Tibet.

And it was the 25th anniversary of the 1988 International Everest Expedition, marking my team’s No 02-No radios-No Sherpas new route up that same face.

————————————————————————

The years, many of them, had passed. Then out of the Internet ether in March 2013 I received an email from Messner with the heading:

61st Trento Film Festival 2013 – Trento Film Festival celebrates 50 years of mountaineering in the USA (May 3rd, 2013) – invitation

Dear Ed,

With reference to the letter you have received from the Trento Film Festival, it is with pleasure that I personally confirm the invitation to take part in the mountaineering event of May 3rd, 2013, to be held in Trento.

You presence as a leading representative of an entire era, will give added prestige to this event that is to me very dear and that is important for the Festival and I think also for mountaineering.

With kindest regards, Reinhold Messner

2013 was shaping up as a stellar year. When Messner’s invite popped into my inbox, I’d only just returned with my wife and daughter from London and North Wales after celebrating the 25th Anniversary of the Neverest Buttress, my Everest Kangshung Face new route. Our entire team plus spouses and children all had assembled for a sold-out “Everest 1988” evening lecture at Britain’s Royal Geographical Society–an unforgettable event. Then we went off cragging in Snowdonia at the Idwal Slabs and shared meals and pints in the pub at the legendary climbers’ hostelry, the Pen-Y-Gwyrd, or PYG. Memories were overflowing; funds were short. Trento Mountainfilm would cover my plane fare and in-Italy expenses, but how was I going to pay the rest of my family’s bills? I juggled, emailed back a YES, prayed–and flew to Italy for ten days.

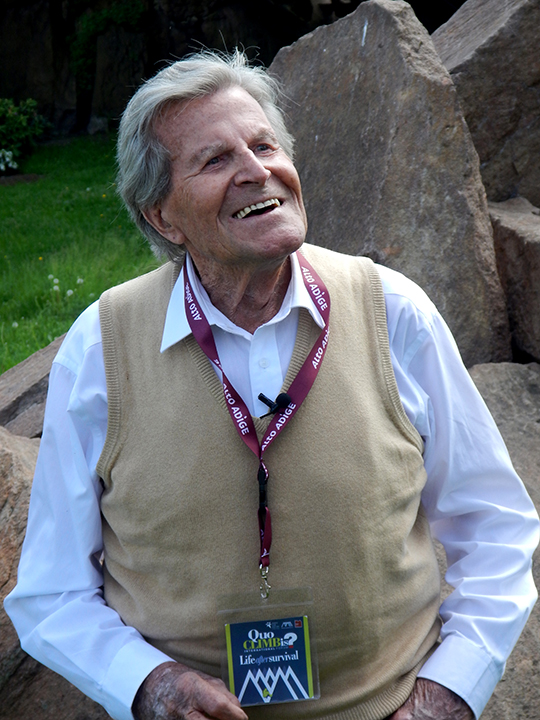

[Photo] Jochen Hemmleb

The day before the Trento Festival opened, I finally visited Messner’s Juval Castle … on a tour my friend Jochen and I had to pay for! An eco-powered green bus drove us and other ticket-buying tourists up the long, curving, steep driveway to the entrance. It was an enchanting and fantastic home Messner had created, now predominantly a museum graced with Buddhist artwork and sculpture, although Reinhold and his family still live there each summer. The uniqueness of the partially unfinished castle, its isolated and singular setting, the views of the surrounding mountains and green valley below were sublimely beautiful.

When I finally met Reinhold in Trento, he pronounced kindly, “Well, you look about the same.”

The festival’s opening night event consisted of Messner interviewing live, on stage, Norman Dhyrenfurth, leader of the 1963 American Everest Expedition, myself, Conrad Anker, and several Italian Himalayan climbers. The focus was on the first American Everest ascent led by Dhyrenfurth, the Golden years of 1960s Yosemite climbing, a bit on George Mallory, and my team’s new route up Everest’s Kangshung Face. Answering Reinhold’s thought-provoking, philosophical, and rapidly-delivered interview questions on the spur of the moment in front of a packed house was a bit nerve-wracking. Obviously, it was not only technological advances in gear (chromoly steel pitons, aluminum carabiners, and more) but the psychological prowess and adaptability of these hardy Yosemite pioneers that led to the first of the Big Walls being climbed by Royal Robbins, Warren Harding, Yvon Chouinard, Tom Frost, and others–but I forgot to add that last bit. Hanging out with Norman Dhyrenfurth, age 95, Norman’s “live-in girlfriend” Maria Sernetz (known as Moidi), Conrad Anker, and Jennifer Lowe-Anker, all of whom I’d met before, was equally memorable.

[Photo] Ed Webster

Two days later, on May 5, we reconvened at Messner’s primary Mountain Museum at Firmian, located in Sigmundskron Castle outside the city of Bolzano. (Bolzano is also home to Otzi, the 3,500-year old Ice Man whom Messner and Hans Kammerlander had been some of the first to inspect just two days after his initial discovery in September 1991.) Messner provocatively titled this day’s event, a panel discussion, Quo CLIMBis?–in English, Life After Survival. Conrad hadn’t been able to stay, but the rest of us attended, his wife Jennifer and I being the sole Americans present.

In today’s era of professional sponsorship, a mountaineer’s financial success is determined by the difficulty and media-salability of their climbs, exploits, and summits reached. Messner’s key question that he challenged all the panelists to answer was this: “How will the sponsored professional climbers of today earn their living once they become too old, when they will naturally be forced to stop their extreme ascents?” It was so very typical of Messner, I reflected, to tackle, head-on, yet another subject no other climber had ever mentioned!

Messner’s beloved Mountain Museums (MMM) consist of five separate museums, each in a different locality and having a unique theme: Firmian (Man’s Relationship with the Mountains), Juval Castle (The Magic of the Mountains), Dolomites at Monte Rite (Geology), Ortles at Sulden (The History of Mountaineering on Ice and the World’s Glaciers), and Ripa at Bruneck Castle (Mountain Cultures, Religions, and Peoples). Messner’s office is at MMM Firmian.

[Photo] Ed Webster

Sitting on Firmian’s hilltop, lawn-covered grounds within the walls of an ancient, ruined (but now partially rebuilt) castle on a bright, warm, sunny day was beyond delightful. Messner guided our group to a large picnic table shaded by a cover. Two of my other Himalayan alpine-style heroes were there. Robert Schauer, who’d pioneered the West Face of Gasherbrum IV in 1985 with Polish legend Voytek Kurtyka, and the Slovenian light-and-fast alpinist Marko Prezelj, who in 1992 made the first ascent of Menlungtse (see Big Reinhold, Little Reinhold, Chapter 2) with fellow Slovenian ace, Andrej Stremfelj.

Then another person arrived. Who was this? I didn’t recognize him. Then he removed his sunglasses. It was Peter Habeler! Waiting momentarily, I held my breath–then exhaled. Everything was friendly and gracious. Habeler and Messner, now shaking hands, warmly greeted one another. And sat together. They’d reconciled some years before. As wine glasses were placed around the table, I realized in a bolt that with beautiful serendipity we were gathered here to help them celebrate their own special occasion. It was three days prior to the 35th anniversary of their first ascent of Mt. Everest without using bottled supplemental oxygen, on May 8, 1978. I was dumbfounded. Wine was poured, glasses were raised, and heartfelt toasts spoken.

[Photo] Ed Webster

Earlier, I’d jotted down cryptic notes for ideas I wanted to express at Life After Survival. But only as the tension built as Messner made his opening remarks to the audience before taking his seat twenty feet from me did I finally get a brainstorm. Furiously I began scribbling–then it was my turn to speak at the podium.

“My life situation at this stage, at age 57, is how do I make a living and how the hell do I pay all the bills? I have a young family, a wife, and a ten-year-old daughter. So exactly the question Reinhold is asking us to answer is precisely what is happening to me at this very second. In fact my wife said, ‘There is no way you can go to Italy. You have to stay home and work and make money! You can’t go over there.’ ”

“To which I replied, ‘But this is the first time I’ve ever gotten an email from Reinhold. I have to go even if we are broke when I get home!”

My remarks, I must say, generated loud applause and laughter. I so wish I’d added that when informing my wife I’d been invited to Italy, I had already emailed Messner back and told him: “Yes, of course I’m coming!”

Instead I told my wife, as gently as possible, “I have no choice, I must go to Italy. I’m sorry, I’ll see you in ten days.”

“I began rock climbing at age eleven,” I explained to the Life After Survival audience. “The first book I read about climbing was about Norman Dhyrenfurth’s first American Mt. Everest Expedition.”

Dyrenfurth was also in attendance that day.

[Photo] Ed Webster

“And so Norman and the other climbers on that expedition were my heroes when I was just a boy. I became a very good rock climber, and eventually an ice climber and mountaineer. But I was never what I’d consider a professional climber. I’ve never thought of myself in that way. I have never been paid to go climbing. I have never been sponsored as an individual. The expeditions I’ve gone on, they were sponsored, but never me.

“I went climbing for the love of climbing, as we all do. For the love of the rocks and the love of the mountains–and when I came home I had no money. But I was rich in memories, in stories–and in photographs. I had not only a talent–thanks to God–for climbing, but a little bit of a talent for writing and photography. And later I thought, I can do some public speaking.

“My advice for young climbers is to diversify your creativity. To follow your heart, but also follow the creative impulses that you have in every direction, wherever they will lead you. And if you are an optimistic person, as I believe I am–someone who always is looking on the sunny side of life–then one of these creative strengths you have as a person will somehow lead you in a way that allows you to make a living from your passion for the mountains.”

There was one final suggestion for aging, formerly-sponsored rock climbers and mountaineers that I didn’t have the mental agility to spontaneously add at my talk’s conclusion:

“You should also learn to grow your own food!”

I got lots of positive feedback from the audience at lunch that day, and later Peter Habeler emailed me: “All you guys on stage got across to us such strong and good feelings, emotions too, which everybody understood clearly. You especially did a fantastic job, including humor, which I think is getting rare in some of the younger generation. On many of my expeditions, having a sense of humor saved us from serious trouble.”

[Photo] Ed Webster Collection

————————————————————————

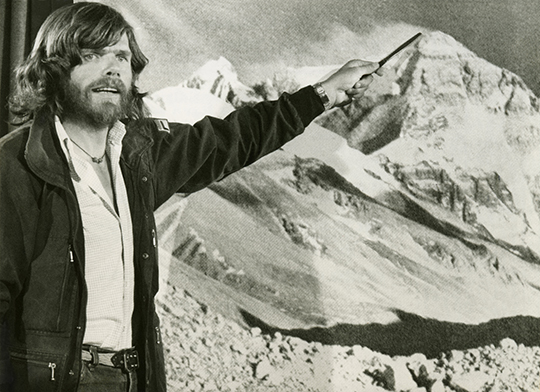

[Press Photo] Ed Webster Collection

During the early 1990s while I recovered from the frostbite injuries I sustained on Mt. Everest, I heard from a friend that during one of his American lectures Reinhold Messner had made complimentary statements highlighting the “good style” of my 1988 team’s Everest Kangshung Face new route. Reinhold had given me his mailing address, so I wrote him to ask if his rumored praise was true. And if so, could I use his laudatory comments as an endorsement on the back cover of my new book, my “Everest-years” autobiography, Snow in the Kingdom?

Years ago, back in that distant, antiquated, bygone, pre-email era, Reinhold answered me in a letter, written on his stationary with an image of Juval Castle at the top. I know I have that precious piece of paper tucked away somewhere for safe-keeping.

“Ed, you heard right,” Reinhold wrote. “This is my opinion and you may use this statement for your book:

“The best ascent of Everest in terms and style of pure adventure.”

When I read Reinhold’s words, this time it was me who got choked up–not on bites of a yak-cheese omelet, but on the quiet surge of humble emotion rising within me.

No alpinist would ever make a “fairer means” ascent of Mt. Everest than Messner himself had boldly accomplished, completely alone upon the mountain, without using bottled oxygen, in part via a new route–but my team came close.

Perhaps I had truly earned the youthful nickname that once upon a time my climbing partners gave me.

Little Reinhold–or even on some days, Tiny Reinie.

[Photo] Ed Webster Collection