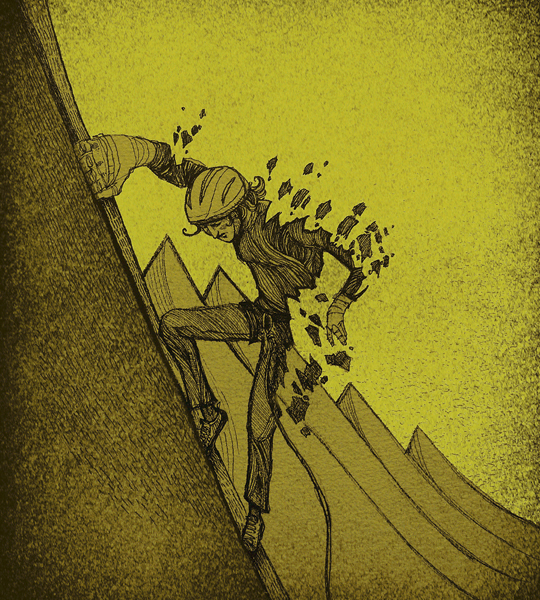

[Illustration] Jeremy Collins from The Climbing Life in Alpinist 46

This story was first published in The Climbing Life section of Alpinist 46. It is included in the Notable List of Best American Sports Writing, 2015 (ed. Glenn Stout and Wright Thompson). Alpinist 46 is available on our online store here. To download a digital version of this issue from the iTunes App Store, click here–Ed.

This is Chapter 1 of “Birth, Sickness, Old Age, Death” by Lizzy Scully. To read Chapter 2, click here.

MY BODY IS FALLING APART at the joints. My last surgeon peeled a frayed mess of cartilage off my left humerus as he fixed a torn labrum. The bones of my shoulder socket grind on each other every time I do thumbs-down hand jams. My orthopedic doctor, rheumatologist and physical therapist agree that I’ll need shoulder-replacement surgery within a decade if I continue to climb cracks. Pain, for the rest of my life, is inevitable if I don’t slow down. But I’d dreamed of Greenland for a decade: fjords lined with towering white granite walls; cracks woven in broken webs up precipitous alpine faces; corrugated ridges leading to narrow, wind-scoured summits. In 2013 my climbing partners and I received grants to travel to the Torssukátak Fjord. At base camp, I listened to a nameless creek rage down the valley. I lay under violent clouds that came from multiple directions and collided silently overhead. I watched a mansion-sized indigo iceberg flip completely over in the waters beneath. And finally, my partners and I boogied and hooted up one of the tall spikes that jutted from the top of the Breakfast Spire.

————————————————————————

Dozens of other spires and sweeping, concave walls surrounded us. We were the first and only people to stand on what appeared to be the peak’s highest point. To the north, west and east, innumerable valleys and glaciers lay before us. To the south, a faraway grey mist hovered over the ocean. Gentle and unmoving, the fog seemed to have no beginning and no end. The initial phantom pains of arthritis shot up my ankles during my early thirties. I was descending a steep, hummock-covered granite incline in Yosemite when I first noticed. Each time I pressed down too hard on my heels, I felt as if I were stepping on knives. So I walked on my toes, wondering whether my load was too heavy. I struggled to keep up with my partners. The inflammation injuries began even earlier, in my late twenties: a half-dozen torn ligaments in my fingers, chronic shoulder tendonitis that worsened into tendonosis, strange back pains, perpetually rolled ankles.

“Your body was just not made for climbing, Lizzy,” my best climbing friend told me. By my thirties, I rarely climbed consecutive days. I assumed I just wasn’t fit enough. So I pushed harder.

“One day, you’re going to have to stop,” an old friend and bodyworker said. But I was determined to be OK, to be better than OK, to explore big walls in foreign countries, to be well respected in the climbing world, to have people say to me, “How was that lead?” rather than ask my male partners. A desire to climb burned through my body, emanating hot from my belly, down my legs and up my chest. This fire drove me to within 200 feet of the summit of Shipton Spire, a giant wall in the Karakoram–even though I’d never been higher than 14,000 feet before. It got me up a two-day first free ascent of the South Howser Minaret in British Columbia, with a small rack, no pins, one partner and just a few liters of water. I was strong. I was capable. I would not get sick, old and die.

————————————————————————

IN MARCH 2010 I was thirty-six, bouldering on twenty-foot-high sandstone cliffs, protected from the wind and drenched in warm winter Colorado sun. Thick, fissured white ice covered Carter Lake a hundred yards below, and in the distance, dark navy storm clouds seemed to roll in place over the Rocky Mountains to the west of the Continental Divide. When I dropped onto the crash pad, sharp, sudden pains exploded in my right ankle.

“Did you roll it?” my girlfriend asked as I lay on the ground.

“I don’t think so.” Two hours later, we were in the hospital, and my ankle had swollen to the size of a melon. The doctors sent me home without answers.

The next day, I returned to the hospital with two grapefruit-sized ankles. My acupuncturist and her boyfriend had to carry me to my emergency-room bed.

“I’m really sorry, but I’m going to have to stick a needle into your ankles to check for infection,” a doctor said.

Oh, my God, the needle was huge. “Morphine,” I told my brother, who had just arrived. “Get me some, please, now.” Despite the narcotic fog, I felt the cold shaft of steel jab deep inside my ankle joints.

————————————————————————

“YOU MUST BE BUMMED you can’t climb!” a well-meaning friend said to me when I got out of the hospital.

Climbing? Who cares about climbing? I couldn’t walk to my third-floor bedroom at the Marpa House, the Buddhist community center where I lived. For a few weeks, I crawled up the stairs. After a month, I could pull myself up using the railings. Two months later, I still couldn’t make it across the six-lane Speer Boulevard in Denver to my Metro State College office before the stoplight changed. One day, an old man with a cane passed me on the sidewalk. He was stooped over, shuffling unsteadily at an uneven pace across the concrete. As he rounded the corner in front of me, I saw his aged profile and the brim of his grey hat for just a second before he disappeared.

————————————————————————

BY JULY 2010, I could still barely walk, but I could sport climb. My friend had shattered his leg a few months prior, and his engagement to his fiancée had recently crumbled; my relationship with my girlfriend had also just fallen apart. He shuffled with a cane. I used both hands to crawl to the crags, but I could still carry more weight than he could. We called ourselves “Team Gimpy.”

My first project ever was in a granite cave at Thunder Ridge in the South Platte. Gently overhanging, it had precise holds, a tweaky crossover traverse and a series of dynos that I had to throw for sideways. I memorized it, practicing the sequences over and over in my head. Because of my pain and exhaustion, I could only manage climbing two days each week–Thursdays and Sundays. But I returned three Sundays to try it; and for three Thursdays, I worked with a personal trainer at the climbing gym to re-create the moves on the bouldering wall.

As I remember, now, the pain abated exactly one day every month–if I was lucky. One of those days fell on the third Sunday in October. The aspen leaves shimmered golden, and I felt that fine line between the seasons: the sunshine still warmed my skin more than the breeze cooled it. I visited the cave with a large group of friends, and we laughed and basked in the sunlit autumn all day. By mid-afternoon, they were whooping and cheering as I floated up the route on my second try.

A few days later, my body shut down again, the pain concentrating in my back this time. A rib had slipped out of alignment with my spine. The arthritis set in with a white, icy fury that lasted through the winter.

————————————————————————

“THIS IS YOUR FIRST EXPERIENCE with birth, old age, sickness and death; you must accept that these things are happening to you,” my Buddhist teacher told me one afternoon. We sat in the fading light among the stone Buddhas and wilting herbs of the Marpa House garden. I cried in his arms.

This is Chapter 1 of “Birth, Sickness, Old Age, Death” by Lizzy Scully. To read Chapter 2, click here.

This story was first published in The Climbing Life section of Alpinist 46. It was included in the Notable List of Best American Sports Writing, 2015 (ed. Glenn Stout and Wright Thompson). Alpinist 46 is available on our online store here. To download a digital version of this issue from the iTunes App Store, click here–Ed.