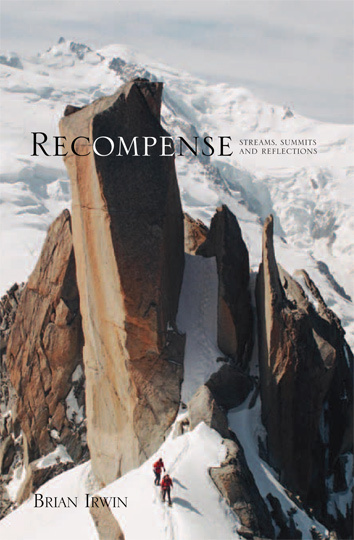

In Brian Irwin’s book Recompense: Streams, Summits and Reflections, the author revisits the moments that shaped him as a writer and a human being. A collection of stories and essays, Recompense explores the author’s relationship with the outdoors from Montana’s Glacier National Park to Maine’s Baxter State Park. Though the book meanders through seemingly unrelated tales, the theme, in Irwin’s words, “is consistent throughout: the outdoor world and how humans interact with it yields fascinating impressions.” The stories are often humorous, occasionally poignant, and always rich with the spirit of open-air indulgence.

Irwin began writing when his father made him keep a journal on family vacations. As he grew older, writing became an increasingly important part of his life. He coupled this passion with a love of the outdoors, and it has taken him across North America and beyond. His travels are always under the banner of climbing, skiing, fly-fishing and, of course, writing. But it is more than just recreational pursuits that occupy Irwin’s prose. As a doctor and a father, his writing is also concerned with the social, cultural and familial matters that lay beneath his adventures.

Divided into three parts, the style plays between memoir, historical essay and outdoor journalism, often employing all three genres within a single piece. Each chapter details not only Irwin’s experience, but that of his partners, who range from bible-toting Christians to brawny New Englanders, and even his two-year-old son. The focus isn’t always the activity itself, but often the dynamics among the characters involved. The study of interactions among folk who adventure together is a common thread in Irwin’s work. Throughout Recompense, the who of the story often outweighs the what.

Irwin avoids the “detailed-account” school of outdoor writing. Instead, he employs humor and vivid characterization to bring his stories to life. In the chapter “Freeski or Die: New Hampshire’s Mount Washington,” Irwin profiles not just the mountains history, but its storied host of characters as well. In another chapter, “Koz, He’s The Man,” Irwin pulls the spotlight away from his ascent of the Grand Teton and places it on the peculiar, over-prepared team he’s joined for the climb. This gives the reader a more entertaining, lighthearted version of the quintessential climbing story.

Despite its successful approach, Recompense falls short in several ways–the most noticeable being the lack of logical progression between stories and parts of the book. No real consistency in date or subject matter explains its organization, resulting in frequent ambiguity over a stories meaning.

Also, readers seeking insightful meditations on the outdoors will be disappointed. While Irwin tells us that the impressions are fascinating, we usually never learn what those impressions are. He experiences many things, some grave and others blissful, but it’s not always clear how he’s affected.

Yet there are exceptions. In The chapter “Recompense,” Rand McNally’s perceived happiness hides a much darker truth. Irwin’s reflections on Rand dissect the uncertainty of human nature with grace and compassion. In the epilogue Irwin again shows his knack for relating essentially recreational activities to deeper, more important human concerns. I wish he’d done so in more of the stories.

Irwin’s writing is strongest when his empathy comes through unmediated, but we don’t always see this side of him. For readers in search of a diverse collection of stories that go beyond the simple retellings of adventures, you will appreciate Irwin’s focus on the social and familial aspects of outdoor recreation. But some stories lack conclusion, and the reader is ultimately left wanting more substance.