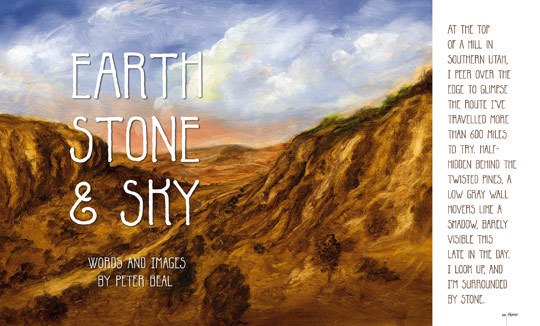

“Earth, Stone and Sky,” Alpinist 32.

The following essay is an addendum to Peter Beal’s feature “Earth, Stone and Sky” in Alpinist 32, available now. For a limited time, subscribe to Alpinist for a year and get an extra issue for free.

When I think of why I climb, I immediately remember my past explorations on rock: sights and sensations, exhilaration, awe, wonder and quiet contemplation. But what truly captures my imagination is the aesthetic grace of climbing, seeing both climber and climb as intertwined in an inextricable lacework of motion, a phenomenon of unparalleled complexity and intensity. I say this as someone who has dedicated much of his adult life to the study of the visual arts through art history, and has spent thousands of hours considering works of art as well as actually making them. I take the question of what makes an art object beautiful or meaningful very seriously.

Can the activity of climbing be a work of art? Can a route? Questions like these were discussed with considerable seriousness in the 1970s. For example, Harold Drasdo’s 1974 essay, “Climbing as Art,” argued that “the likeness [of climbing and art] is extensive and important.” Yet he focused on a romantic vision of the natural sublime–the idea of a setting or feature that overpowers our ability to comprehend it–to support this view. Indeed, Drasdo proposed that climbs of “value and importance” must “satisf[y] certain uncodified but stringent aesthetic criteria.” His belief is clear: for a climb to be significant, it must be held to the same aesthetic standards as great works of art.

Landscape with Two Trees. Oil on Panel, 8″x10″, 2009.

“My paintings are primarily about space and creating a sense of atmospheric depth in the picture frame,” Peter Beal said. “I have long been drawn to the unique perceptions that being high off the ground allows. Not so much the aspect of looking down but of looking out across the terrain. Ever since I was a beginner in the sport of climbing, the prospect of infinite distance and atmosphere has attracted me. The sense of movement and light that this position engenders is one of the most important appeals of the sport of climbing to me.” [Painting] Peter Beal

Certainly consensus has eroded regarding these criteria and the values they represent. In fact, the lack of general agreement within the climbing community about what constitutes valid or ethical climbing practice represents a crisis of sorts about the meaning of climbing. Yet as the cliche has it, “Crisis can also mean opportunity.” The free-range nature of the sport today means a greater opportunity to transcend those fragmented strictures on the meaning of climbing. Historical parallels exist in the study of art itself. Study of the “great works” of the past has led to a more comprehensive conception of art and its history.

To me, to focus on the grand, the dangerous, the awe-inspiring seems increasingly misplaced, for the conceptions that underlie that vision of climbing have gradually eroded. Despite, and ironically, as a result of, the attempted commercialization of the sport to sell itself as extreme or edgy, it is clear to many of us that climbing is anything but. Yet it cannot be otherwise. The old emphasis on exploration, first ascents, and adventure has had to contend with a vastly expanded knowledge of geography, climbing skill, physical strength and improved equipment–which all but guarantee that “futuristic” climbs are a foregone conclusion. In other words, the outer frontier in any objective sense is now closed in climbing.

It’s my view that only within inner frontiers does the art of climbing have any future. We have yet to see very many contemporary portrayals of the inner vision of the climber that compare with examples from the 1960s and ’70s. Yet there is no limit for more introspective insights on the sport (or sports) of climbing. It seems to me that it is time for these voices to be heard, for a new aesthetic in climbing to emerge.

Cloud Study. Oil on Panel, 10″x10″, 2010. [Painting] Peter Beal