“[We didn’t climb anything else] after sending the route [Golden Lunacy], [because] the weather was very bad, with storms and constant rain. But, while kayaking, we found some unclimbed areas with walls 700 to 900 meters high,” said Kaszlikowski.

[Photo] David Kaszlikowski

Wild places drive us. In the hype surrounding grades, summits, redpoints and the like, the places themselves sometimes are forgotten. Often we forget that Himalayan expeditions once required treks of hundreds of miles–just to reach base camp–when, in 2005, a helicopter landed on Mt. Everest’s summit. It’s hard to remember that John Muir’s pioneering scrambles and climbs in Yosemite, while non-technical by today’s standards, were not aided by miles of concrete and asphalt, cafeterias, gear-shops, or medical facilities that today’s Camp 4 dirtbags access.

This was an exellent place to leave the boats during the climbing, however, it did necessitate a lengthy traverse to the true start of the route. [Photo] David Kaszlikowski

Thankfully, some have not forgotten that the inaccessibility of a place can render its climbing all the more inspiring. Issue 19’s “Elsewhere” tells the story of a group of sailing climbers who travel thousands of miles in a “fifty foot surfboard”–the yacht named Northanger–to make the alpine style first ascent of Mt. Foster on Antarctica’s Smith Island.

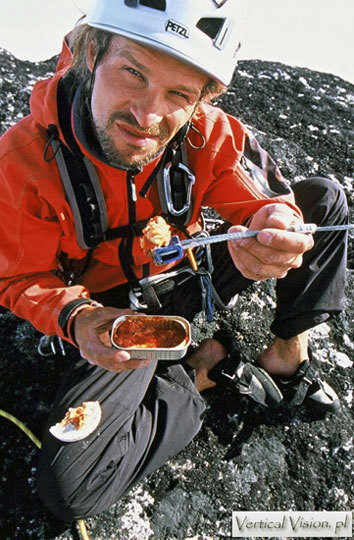

“There is no spoon.” No, there isn’t, but David uses his ingenuity to realize just one of the many tiny joys of alpine climbing. [Photo] David Kaszlikowski

Sometimes, simply creating your own inaccessibility is enough. In 1996, a Swede named Goran Kropp rode his specially designed bicycle, loaded with 240 pounds of equipment, over 16,000 miles, managing to fit in two summit attempts on Everest (one was successful) in the process.

August 14, Polish alpinists completed their new route on what the Inuit call Maujit Qaqarssuasia (also known as The Thumbnail). The 1500 meter wall rises straight from the water, making it the highest sea cliff in the world. The team’s route, Golden Lunacy, is one of only four on the wall. [Photo] David Kaszlikowski

These stories are notable because of their rarity. In a world where road building is more common than tree planting, the places that we go become less wild every second.

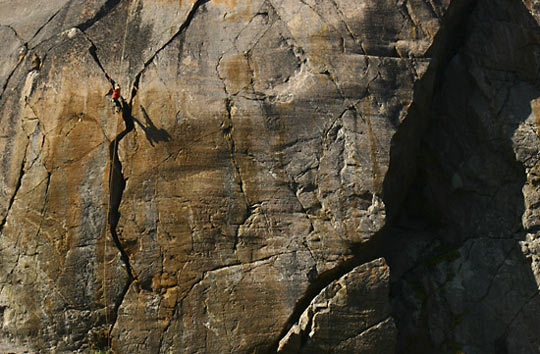

On the third day of the route, the team encountered 60 meters of sustained 7a+ (5.12a/b) lieback crack. It proved to be the most difficult section of the route. [Photo] David Kaszlikowski

The number of inaccessible places may be shrinking, but few places are harder for humans to navigate than the Arctic and sub-Arctic fjords of Greenland, the world’s largest island, covered almost entirely by an ice sheet. The southern city of Narsarsuaq reports an average high temperature of 56 degrees in August. A narrow strip of open coastline ringing the island is etched by thousands of steep sided, narrow fjords. Every day calving glaciers spill hundreds of icebergs into the sea, where Inuit easily navigate kayaks along the ice-chocked coastline.

When Poles, Eliza Kubarska and David Kaszlikowski set out to climb Maujit Qaqarssuasia in Southern Greenland’s Torssakutak area, they too chose kayaks as their transport. Although not a 700-mile trek or a globe-crossing sail, their journey allowed them “to explore the cliffs but also have our share of adventure.”

The pair set up their self-sufficient basecamp on Pamialluk Island, two iceberg-strewn kilometers from their climbing objective, one of the tallest sea cliffs in the world. “It was a beautiful climb on solid granite,” David said. “Some of the most interesting parts were wet offwidths done by Eliza; terribly difficult. The last pitch to the peak was a 60-meter tower with an amazing view. Unfortunately, just after we stood on the summit, clouds started piling over our heads, and in a little while we couldn’t see farther than 100 meters.”

The 1500-meter line on the face took the team a few weeks to complete, as their desire to free the route conflicted with the weather’s desire to drench them for days at a time. But eventually they established Golden Lunacy (5.12a/b, 1500m) with a minimum of fixed lines and a total of five bolts.

After team reached the fjords around Torssukattak area , they decided to use sea kayaks as their mean of transport.They climbed directly from the sea, and they padlled over seventy miles in the area in search for new walls to climb. The wild character of the location was preserved, at least this time. “That was one of my most beautiful expeditions,” David said. “Every day we were passing icebergs. We met very hospitable Greenlandic people at a village called Appilattoq and watched the Northern Lights. We picked berries by the handful, and Eliza learned to paddle! We definitely have to return to those walls.”

Alpinist presents the photographs of David Kaszlikowski, from his trip to Greenland with Eliza Kubarska this August.

After their big wall climb, team opened only few short routes near Innuit village of Appillttoq, the rest of their time team spent in their kayaks in attempt to find new climbing areas. [Photo] David Kaszlikowski

On the team’s first attempt, bad weather prompted a retreat. The team traversed into what proved to be a much more technical couloir descent than what they had expected. Lacking ice axes and crampons, the team was hampered by crevasses, waterfalls, stuck ropes, and cold temperatures. The descent took six hours. High seas precluded the use of the kayaks, so the pair was forced to bivy sitting on their ropes, with plastic bags held over their heads as impromptu rain protection. [Photo] David Kaszlikowski

Eliza’s hands after the unpleasant couloir descent. Wet weather was a constant problem for the climbers. [Photo] David Kaszlikowski

The pair was surrounded by the sounds of creaking and crashing ice as the icebergs settled, shifted and collapsed around them. Icebergs, without the support of surrounding ice, and constantly nibbled by saltwater, are in a constant state of disintegration. Kayaks allowed for much easier navigation through the ice than a larger craft would have. [Photo] David Kaszlikowski

A series of very wet rappells brought the team down from their first attempt. [Photo] David Kaszlikowski

Eliza Kubarska and David Kaszlikowski in front of Maujit Qaqarssuasia after the completion of their new route. “What we found in the fjords is undoubtedly one of the best granite areas in the world.” [Photo] David Kaszlikowski