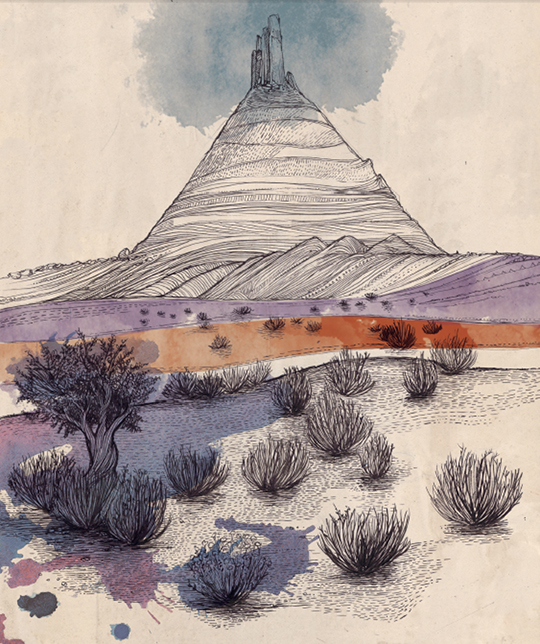

[Illustration] Jeremy Collins

[This story was first published in The Climbing Life section of Alpinist 48. This issue is available on our online store and for digital download on iTunes-Ed.]

NO PLACE SUCKS UP SUN like the Johnny Cat enclave at the Cat Wall, Indian Creek. The maroon cliffs are striped with perfect, cleaved fissures like vertical gateways into a hidden world. The desert heat can be oppressive, but in late autumn, the low golden rays cast long shadows over the walls.

We, the climbers–all smiles, scrapes, taped hands and colorful costumes–are the gatekeepers against anything from the outside that might intrude. I’m reminded of Kerouac and his Beat Generation: they left behind the postwar clutter of new televisions, shiny cars and urban sprawl to climb mountains and collect frost-white granite, blazing meteors and volcanic ash in words. We, too, attempt to live simply, beaten by wind and by stone, trying to access something larger, something enclosed in the rocks and in our selves.

We watch Mark climb that “thing to the right of Johnny Cat.” Mark wears a black-and gold cape that glitters in the sun. The crack is so narrow his fingers must feel as if they’re being run over by an eighteen-wheeler.

He places tiny cams while the cape dangles and then flaps horizontally. This could be a movie. The maroon wall is the screen, and our superhero is engaged in a battle for good; the villain is gravity, or perhaps, doubt and fear. Our hero screams and jams and finds tiny edges for his feet. And then, Bam!, he’s flying off the rock. The crowd cheers. Another year of Creeksgiving has kicked off.

————————————————————————

[Photo] Luke Mehall

AN ACID TEST OF SORTS for the climbing community, this non-event was born of friends gathering for Thanksgiving weekend at the Super Bowl campsite in the early 2000s. There was a man they called The Mayor, a stubble faced sage who took care of everyone with a slyly welcoming grin.

One year, it rains as it never does in the desert: continuously, filling up long-forgotten washes and ensuring that the Wingate sandstone is soaked for days.

Sure, we could start drinking, but instead we stage a 4K footrace around the campground. I pull a variety of costumes out of a duffel bag. Our friend Shaun works for an athletic company, and he produces a bag of socks and hats. That night, we have a dance-off. People wrestle in the mud–grown men driven to madness by rain and alcohol, writhing on the desert floor.

“This is America’s greatest footrace,” Adam proclaims the next year. We run a half-marathon beneath a dark-blue sky, just a handful of us, one wearing a one-piece catsuit, another a Luigi costume. We jog from Super Bowl to the distant ramparts of South Six-Shooter Peak; we’ll Jumar up it before running back.

Adam is a college friend from Gunnison, Colorado. When I met him, he was into ecstasy and raver parties. Then he grew up and sought adventure in other forms. He was once robbed at gunpoint, and he told me, wide-eyed, “It was so cool.” He skis powder, floats rivers, loves women and screams about “cutting the rope” Vertical Limit-style at the climbing gym. His eyes are as blue and deep as glacial tarns. He’s ready, at any moment, to erupt into maniacal laughter.

I follow his wild blond mane through a wash, silent, moving slowly. My feet sink into the fine pink grains; my breath guides me through sand and stone.

On the way back, we gaze at distant landmarks: North Six-Shooter, the Cliffs of Insanity, the Happy Submarine. Six-Shooter rises proud and lean, like a crimson pistol. To our right is the Submarine; it has all the features of a sub, including a tiny periscope.

I fall behind. Adam carries on, his Jim Bridwell-inspired shirt glistening with psychedelic colors, and then he fades into the desert, disappearing behind a small hill. That night at the Super Bowl, the Mayor attends to the turkeys. He wears a big black mustache and devil’s horns. While we were running, he spent the entire day cooking six turkeys in carefully excavated pits.

A group of sixty gathers around the fire, and each climber takes a turn stating what he or she is thankful for. At the dance-off, a man in a pink suit ekes out a narrow victory over a guy who strips down to his underwear and sprays everyone with cheap champagne. The liquid is sticky, a sugary dew upon our faces.

The following noon, thirty of us arrive at the Pistol Whipped Wall. The bright greens and yellows of our outfits replace the long ago-wilted desert flowers. Adam has to leave for Salt Lake City. He and his girlfriend, Amber, say the things that people who are leaving Indian Creek say: “Sorry we have to bail. I’ve got work tomorrow,” “We’ll see you soon, though–you’re coming to Salt Lake this winter, right?” In front of them are the cracks and the secret world within the stone. Behind is the valley with its coruscations of sandstone running to the horizon, the dusty floor dotted with cottonwoods and red willows, silent with oncoming winter.

When the weather is good and the body is able, no one ever wants to leave. We’ve just met Amber, and she jokes about writing us letters. I love people who write letters, and I tell her so.

A month later while skiing, Adam dies in an avalanche. Thirty years old. I haven’t known the death of a close friend until now, and part of him stays with me, a voice in my head. Sometimes it’s as if he’s still there, standing in the iron-stained dust below the crag that perfectly hungover long-ago Friday.

————————————————————————

[Photo] Mike Shaw

THE NEXT YEAR, Shaun builds a wooden structure he names “Adam’s Arch”; adorned with prayer flags, it’s the starting line for the races. By now, nearly all visitors use the name Creeksgiving. The numbers swell in the Super Bowl. Our dinner table is as long as Supercrack, with a hundred-person queue.

During dinner we have Timmy Foulkes’s Television, our imaginary TV station, with programming ranging from the telephone game to mustache competitions. Revelers wear rabbit costumes; there is a man with a horse head, a woman in a skintight fishnet top and black pleather pants. And there is pink, lots of pink–a pink wig, pink tights–and gold, so much gold.

Sixty people pass a strip of LED lighting across our checkered linoleum dance floor. We dance until the stars fade into alpenglow.

Creeksgiving has grown too big. We know it. Apparently, so do the authorities. The following spring at Creekster (a knock-off mini-celebration during Easter), we catch the Utah police spying from the bushes. We decide to have fun with them and stage a silent

mustache competition. I imagine those officers back at the station: “Well, Sarge, we tried to bust those hooligans, but they were actually really quiet. They did hold a mustache competition, though.” And then, just like that, our Creeksgiving is over. We don’t go the following year.

We’re all getting older. We’ve cried enough tears of joy at weddings to make an arroyo flow. We’re less committed to living like dirtbags, and more committed to something else. You could call it love. Or life. Or adulthood. The word Creeksgiving, however, remains part of the lexicon, and climbers still gather under its name. Every autumn, I see the forum posts: “Who’s going to Creeksgiving this year?”

I was fortunate to partake in this absurd celebration when climbers with wigs took whimsical whippers, and we danced as if no one was watching. Creeksgiving was our own little Golden Age, encapsulated in magic and reverie, a point in time when if a man in a gilded cape had simply taken flight into the heavens or disappeared into the rock, I wouldn’t have been surprised.

It never occurred to me that those moments could simply vanish, or that any one of us could. We never do; if we’re living right, we simply live, in the moment.

I wish I could say I hold on to some ideal parting image of Adam–say, at that perfect instant atop a sandstone tower, where the afterburn of adventure blends with the camaraderie of partnership. Instead, I recall blurry fragments. Adam’s house in Salt Lake City days after his death, filled with his paperback books, skis, bikes and one lone flower, still blooming and cared for by his roommates. His lucky piece, the pink Tri-Cam, which we finally discovered in a snow patch in front of his house. His quiet voice uttering the best piece of advice he ever gave me, “Just breathe.” And the time at the Creek when Adam and I sat on a tailgate and saw a shooting star blaze across the sky. In an instant, the object was gone, but countless other stars dotted the heavens. We sat there, breathing, dreaming, drifting off toward sleep.

“Wouldn’t it be crazy to witness a comet hit the earth and destroy us all?” I asked. All Adam said was, “That would be so awesome!”

I know that in whatever incarnation future Creeksgivings will take, Adam will be there–closest to us when we’re scraping up some sandstone crack that cuts deep into raw skin or running through a desert wash draped in psychedelic hues or gathering with our faces lit by firelight–a spirit made of stardust, illuminating our bacchanal from the proscenium arch of the heavens.

[The description of the Beat Generation’s writing is based on passages from Jack Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums and Gary Snyder’s Danger on Peaks.–Ed.]