“George Lowe, Mark Chapman and I were at the top of the first pitch of the Nose when I heard what sounded like an explosion,” wrote 69-year-old Jim Donini on SuperTopo.com’s forum. “I looked up and was shocked to see an enormous dust cloud on the Gray Bands and rocks heading our way. We ducked and were showered by small rocks and sand. The main load went just to our right. A few minutes later we heard a yell for help.”

“We were in the impact zone and helpless,” Chapman responded. “I started yelling–everyone started yelling ‘Rock! Rock!’ There was that moment in time staring up and waiting for the impact. We were helpless–fish in a barrel. As the rock started raining down I was looking up hoping to dodge the worst of it. I briefly thought of how I was the one without a helmet. I realized there was too much coming down and I had to seek shelter. There was none. I covered my head as best I could with my arms and hugged the rock waiting for the impact that would split my head open. Miraculously this never happened. The worst passed just to the east of us.”

“There was a somber mood–especially among the climbers,” he continued. “We had lost one of our own. It could just as easily been any one of us. Climbing accidents happen. People sometimes die climbing but we never think it will ever actually be you or me. If we did we would probably quit climbing.”

Mason Robison, 38, a stonemason from Columbia Falls and partner Marc Venery, 28, also from Montana, were ascending El Capitan’s Muir Wall (VI 5.10 A2 or C3+, 33 pitches, 2,900′) in Yosemite Valley. They were 600 feet from the summit when the incident occurred. The experienced team was making a hammerless ascent of the route and had already climbed through the route’s three clean cruxes.

Shortly after the incident Tom Evans arrived in El Cap Meadow. Evans has been photographing El Cap climbers since the mid 1990s. Upon his arrival at the bridge, he was approached by Law Enforcement Officer (LEO) Ben Doyle, who was there responding to the call for help and reports of falling rock which came soon after 9:15 a.m. on May 19. Evans, using his telephoto lens and camera, zoomed in the wall. “I have never seen such a grisly, terrible scene,” he wrote on his website, elcapreport.com.

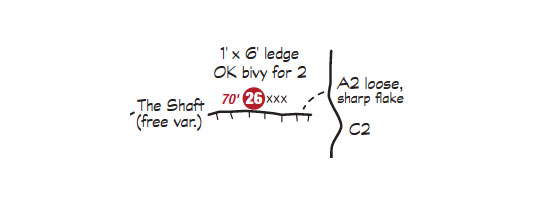

Shortly before falling, Robison had set off into terrain labeled in SuperTopo: Yosemite Big Walls as “A2 loose, sharp flake.” Twenty feet from the anchor he placed a cam behind a triangle-shaped flake in a roof. This caused it to dislodge towards his waist and caused him to fall.

When the block released, it cut Robison’s dynamic lead rope a few feet below his tie-in point. With his primary rope severed, he continued to descend approximately 230 feet onto the end of his static rope clipped to the back of his harness. When Robison reached the end, the impact force was so great it caused immediate death. Static lines have an average elongation of just 5% and are not designed to take a lead fall. Dynamic ropes stretch with an average elongation of 30%.

Venery, with his partner now lifeless at the end of the static line, worried that the rock fall may have triggered more falling rock, killing or injuring additional climbers before hitting the ground. He immediately called 911 but cell reception was spotty. He yelled for help, and Search and Rescue (SAR) responded to his call.

At 12:30 p.m. Helicopter 551 brought SAR members to the top of El Cap, and they prepared to remove the climbers from the wall. Seasoned LEO rescue members Jack Hoeflich and Ed Visnovske were lowered to the climbers where Robison, 200 feet below Venery, was pronounced dead. “Scott Jacobs served as the Incident Commander,” wrote Park Personal Relations Manager Kari Cobbs in an email.

Yosemite Geologist Greg M. Stock, Ph.D. P.G 1, stated on a recent phone call that the block was sitting under a big roof. “The roof itself was formed by a rock fall that may have happened thousands of years ago. When that rock fall occurred a little bit of rock stayed there. And that is what was dislodged during that incident. Stock continued, “I still wonder if the block that was dislodged might have generated some additional falling rock. Some rock falls double in volume as they come down the cliff.”

Stock says the block looks like blocks climbers use all the time and that other teams had likely placed gear behind it. He believes that weathering had more to do with the block dislodging and not just Robison placing gear behind it.

Stock has climbed two El Cap routes and used a static line on both occasions to haul his bags up the wall. (I also prefer to use a static line to haul my bags because it is stronger and more durable than dynamic rope.) Stock stated that around the same time of Robison’s death, another rock fall occurred on near the West Face of El Cap. “It generated a large dust cloud. It was an exclamation point in a way that rock falls are common either natural or otherwise and that anyone at the base would be affected. Any big wall is in the path of potential rock falls,” Stock said.

Stock believes the area where the rock fall took place on the Muir Wall is now safer. “It’s really sad that it had to happen that way in order to make it that way,” he said over the phone.

Senior SAR member John Dill believes the block to be 3′ x 3′ x 2′ and recalls several deaths from rock fall during his tenure. “Two years ago an Austrian on Half Dome pulled a flake, which cut his rope, and he fell to the base. A year or two before that a Korean pulled a block on the Nose and survived but his rope was partially cut through. Before that a German or Austrian pulled a block at the top of Pancake Flake (also on the Nose), I think, which cut his rope. I believe he fell to the end of the haul line, which broke.”

TM Herbert and Yvon Chouinard first climbed the Muir Wall, one of El Cap’s greatest lines, in 1965. It was the first route on El Capitan that was put up without fixed ropes or reconnaissance. It was also the first time an El Cap first ascent was done by a team of two. Towards the top of the route, low on bolts and exhausted, Chouinard recounted that his partner TM “placed pitons behind the gigantic loose blocks that could break off at any moment” (1966 American Alpine Journal).

Mason Robison attended Columbia Falls High School and was on the cross-country team. He grew up exploring the mountains and rocks surrounding his home and became an experienced rock and ice climber. He was known for having robust lungs, which helped him link up multiple peaks in a day. He also sang and played the banjo. His work, including building custom fireplaces, provided him with the income and flexible schedule to travel to the Himalaya, among other locations, and to climb big walls in Yosemite.

This was the second time a climbing tragedy occurred in the Robison family. On July 3, 1998, Mason’s brother, Mark and his partner Chris Foster of Whitefish, Montana, both died when a cornice collapsed a few hundred feet from the summit of Rainbow Peak in Glacier National Park. Robison originally planned to be on this climb but changed his mind at the last minute due to other plans and the long approach. Later that year Robison was married.

Robison and Venery’s climbing partnership extended back 17 years. Once back at the Valley floor, Venery spent two days driving back to Montana to recount the events to Robison’s family.