[Below are author Jack Tackle’s reflections on “Down to the Wire” from Alpinist 1–Winter 2002-2003–Ed.]

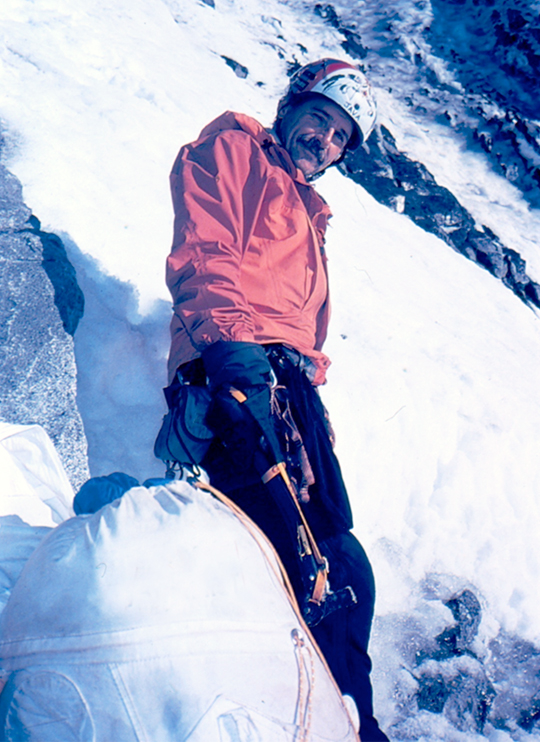

May 20, 2016: This story is about recovering from a debilitating sickness and then traveling to Mt. Augusta (14,072′), Saint Elias Mountains, Yukon Territories. High on the peak’s north face, I was clocked by a rock and rescued from the wall a few days later by Pararescue Specialists (known as parajumpers, or PJs), highly trained members of the Airforce Special Forces. PJ Dave Shuman, the bravest man I know, was lowered 140 feet down the wire out of the side of a hovering ship to rescue me from the face. My climbing partner on Mt. Augusta, Charlie Sassara, played a huge role in saving my life–all told, about 30 people were involved in the rescue.

The common thread here is that I came back from a life-changing series of medical challenges. First viral spinal meningitis, then Guillian-Barre Syndrome, a rare, debilitating auto-immune disease. I was able to get better and try to get back to where I was, so to speak, despite some neurological damage. The desire to get back into the greater ranges is what got me back on the horse to go climbing again.

Over the past 43 years, I have pursued all types of climbing throughout many different ranges of the world while always maintaining an eye on unclimbed routes. I have done numerous trips to the Himalaya, South America and Alaska. I have done 35 separate trips to Alaska since 1976 that included both attempts and successes. I’ve completed 17 major first ascents in Alaska’s various ranges.

I survived my accident on Mt. Augusta, in part, from learning how to deal with the pain of my sicknesses and how to survive. That was back in 2000 and 2001. Since my near-fatal accident, I’ve done two new routes on both Mt. Huntington (12,241′), and, in 2009, Jay Smith and I did four new routes in the Alaska Range, including a 4,000 foot route up Mt. Thunder.

So, the theme to me is that, despite my previous injuries and accident, I’m still willing to go climb big routes in big mountains. Most people my age aren’t doing that.

—Jack Tackle, Bozeman Montana

[Photo] Charlie Sassara collection

————————————————————————

EVERYTHING IS BLACK AND SILENT. My right cheek stings against the coarse, cold snow. There is an acrid smell and taste in my mouth as it fills with blood. The entangled rack hangs precariously from my left shoulder. I struggle not to lose it but am incapable of preventing it from falling down the face. Except for my head and mouth, I am completely paralyzed.

“Christ! Not again,” I think.

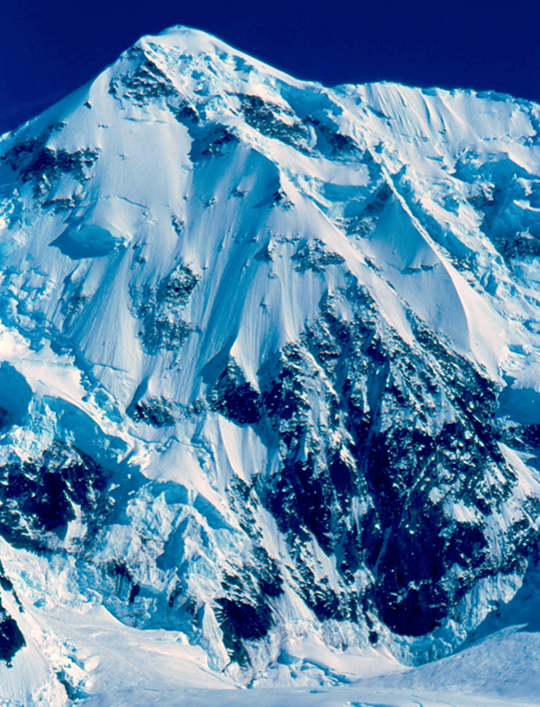

Three days before, on June 15, as I first peered through my binoculars at the north face of Mt. Augusta, I realized Charlie Sassara and I were in for more of a challenge than we anticipated. Blue ribbons of ice wove their way from the bergschrund to the top of the face, forming a perfect 3,000-foot line as they connected through the rock bands. It was more technical than I had imagined from the photographs. Nonetheless, I was excited by the prospect.

It had been a long time since I had been in the big mountains of Alaska. Two years before, after an attempt on the Orge, I contracted viral meningitis in Skardu, Pakistan, and spent six days in the hospital in Bozeman, Montana, with the worst headache of my life. Three weeks after getting out of the hospital, I still couldn’t walk five minutes up the road. Five months later, in January 2001, I was in Argentina at 13,000 feet guiding Aconcagua when an unbelievable pain struck me down. In the Intensive Care Unit of the Mendoza Hospital, my condition deteriorated quickly. When the Argentine doctors were unable to correctly assess my condition, my friend Tim Forbes arranged for a Learjet air evacuation. By the time the Lear got me home to Wyoming, I was almost an obituary. I had contacted Guillian-Barre Syndrome and was left almost totally paralyzed and in the hospital for fifty-two days.

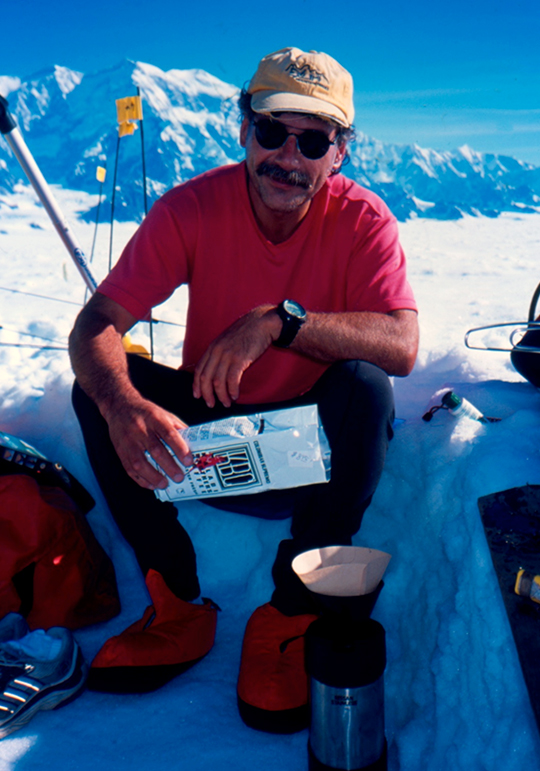

My long and arduous recovery continued into 2002. Now, eighteen months later, I was back.

[Photo] Jack Tackle

————————————————————————

Mt. Augusta is a 14,000-foot peak that straddles the US/Canadian border. The south side of the mountain lies on American soil; the north side belongs to Canada. I had wanted an objective that was challenging, but not overwhelming. I needed to be cognizant of the altitude and the cold: my feet still went numb in cold conditions, the the result of the Guillian-Barre. Mount Augusta seemed like an appropriate goal.

Charlie and I spent a day and a half after we first landed looking at the face, watching it, glazing it constantly, and doing our homework. We did most of the approach as well. Thirty-six hours after arriving, we left at 4 a.m., skinning on top of an incredibly hard crust that left almost no trace of our passing. Two miles and 1,500 feet of elevation gain later we cached the skis, roped up, put our crampons on and headed across the final cirque, scampering quickly beneath the seracs. We reached the bergschrund at 8 a.m.

It was fifteen degrees Fahrenheit when I racked up.

“Would it be OK if I took the first pitch?” I asked Charlie.

I hadn’t led an unclimbed pitch of ice in three years.

“It’s just like riding a bike, my man,” I said quietly to myself.

————————————————————————

My goal is to always try to stick to pure alpine-style climbing on new routes. We didn’t have a bolt kit and we didn’t take jumars. We wanted to lead with packs, climb in blocks and swing leads. On the first pitch, however, bizarre snow, overhanging in a couple of sections, had consolidated into ice, precluding a lead (at least for me) with the sack.

The pitch took two ice screws and a shitty Spectre. I found decent rock anchors, hauled the pack, and brought Charlie up. As I belayed, I gazed across the cirque at the serac walls we had sprinted beneath just minutes before. A huge cloud engulfed the glacier below with windblast and debris. Timing is everything.

The opaque sky that dominates north faces at this latitude sat calmly on the horizon. All was quiet for now.

“I can still do this,” I reflected to myself. “Beats the ICU.”

Charlie led through, climbing with the pack. When he reached an overhanging overlap that had bad protection, he wisely hung it from a piece of gear, pulled the roof, and led the rest of the thin mixed slab to the end of the rope.

From that point on we led every pitch with a pack, swapping leads and even simul-climbing a bit between the third and fourth pitch. The climbing was fun but demanding. When it was steep, the snow was shite; only thin iron was useful, and it was difficult to place in the shattered metamorphic rock. Nonetheless, many of the pitches were classic: enjoyable alpine ice flowing smoothly up the face.

By 8 p.m. we had reached the center of the face. We could see a protruding rib of snow ahead. From base camp we had identified this as the only site where we might be able to chop a bivouac ledge.

I led the twelfth pitch of belayed climbing over to a sound rock buttress with bomber anchors, then brought up Charlie. Now the Alaskan ledgechopping fest began. As often happens when you really need the ice to be thick and fat, we hit rock. The ledge was one person wide.

I rappelled sixty feet to look at two other possible sites. They sucked.

“I saw two other ledges on my way up,” Charlie said when I reached him. “Why don’t you go above to look?”

Leaving my pack, I tied into one of the eight-mil ropes, took the rack, and climbed up forty feet on easy snow and some moderate mixed ground to the first ledge, where I placed a .75 Camelot. The ledge sloped badly under the snow cover, and was no better than what we had below.

I moved up right via a small groove toward a smaller ledge twenty-five feet above. All of a sudden I saw to my left the perfect Stopper placement: a beautiful thin crack with a classic taper, the kind that lets you just drop that number three wire into the bomber placement. I nested it, tugging once, clipped a long runner into it–and off I went, to the next ledge.

As before, the ledge was inadequate. I kicked the snow with my feet. I looked at my boots, watching the crampons slice through the snow.

Then, everything was black.

[Photo] Jack Tackle

————————————————————————

I hung upside down, my face in the snow, paralyzed except for my head. I couldn’t move my arms or legs. I couldn’t do anything except yell to Charlie. I had no idea what had happened to me. All I knew was that I was severely injured and paralyzed. Again. Communication with Charlie was random: I was stunned, in incredible pain, and incapable of doing anything–and I still didn’t understand why.

“You’ve been nailed by a rock!” Charlie yelled.

I neither saw nor heard it. A rock the size of a briefcase had come from the upper part of the face and hit me, literally out of the blue. It hadn’t touched the wall for a long time. Charlie saw it silhouetted against the sky as it traveled at terminal velocity into my back. He yelled, but I never heard him.

The rock had glanced against my head, cutting into my scalp beneath my helmet, then shot across my right shoulder and into my neck and back at a forty-five-degree angle. The rock had knocked me forty or fifty feet onto the perfectly placed Stopper. I stopped on the snow twenty feet above Charlie, from which point he then lowered me directly to the ledge.

I flopped around like a rag doll. When he grabbed my chest to turn me around, a tremendous pain shot from both sides of my sternum. He used my parka as a litter to reposition me on the ledge; I screamed with the slightest movement. Blood covered my entire head. Three of my teeth were gone and my face was covered in blood as well.

“How hard is it to hoist me?” I croaked.

“I’m the strongest motherfucker on the planet,” he said. His focus was intense. “Don’t worry.”

Any movement, any contact from Charlie made me retch in agony. I had a deeply sickening sensation of fear, and shock, and pain. When he finally got me sitting on the ledge, I slumped over like a wet dishrag.

I was convinced that I had broken parts of my back and possibly my shoulders, my left scapula in particular. I couldn’t use my left arm. Slowly-Charlie later told me it took some fifteen minutes–my arms regained sensation, followed by my legs fifteen minutes after that. But nothing worked above my left hand, not the elbow or shoulder or anything else. The excruciating pain in my chest and the sensation in my torso led me to believe I had internal injuries. Charlie felt very much the same.

My vision of the world shrank down to just three things: Charlie, the ledge, and myself.

[Photo] Charlie Sassara

————————————————————————

Over the course of the next hour, Charlie went to work, dutifully melting snow to get food and water in me, dressing me in more clothes, trying to figure out what to do next.

I faded in and out. As I came back, I had the odd sense that I needed to keep tabs on Charlie. A huge weight of responsibility had been unfairly thrust upon his shoulders.

“Hey, Charlie, how are you doing?”

“I am awesome.”

He was so focused, so attentive, so in the moment of just doing the work. He was fantastic–but I knew he was lying.

————————————————————————

The juxtaposition of what Charlie was faced with now and what had occurred to me on my first attempt of the Isis Face of Denali twenty-three years earlier came to mind. In 1979 Ken Currens and I had climbed 2,000 feet on the southeast face of Denali’s south buttress over the course of two days. At a sloping stance I anchored myself to a deadman and an ice axe shoved in bad snow, brought him up, then gave him a hip belay as he climbed above me. Thirty feet up, he put in an old Chouinard ice screw and continued to the end of the rope. He stamped out a platform and tried to place a piton in the rock for the belay anchor. As he was hammering in the pin, the platform collapsed, causing him to topple over backward. He rocketed past me, falling 250 feet before stopping on the single screw. My anchor failed. The one screw held the fall.

Kenny had suffered a severe head wound and a broken femur. The only option was to secure him and leave him alone while I tried to get help. I downclimbed the face, skied ten miles unroped down the West Fork of the Ruth Glacier and finally radioed our bush pilot for help.

Now, it was my turn to be left alone. Now, the roles were reversed.

————————————————————————

I knew even before the accident that I could depend on Charlie for anything. Trust. It’s what a partnership in the alpine arena is all about. You have to know implicitly that it’s there before you go. Then, once you pull the trigger and begin, you never have to think about whether or not you can rely on your partner.

“Do you think you can rappel, Jack?”

“No.”

“Can I lower you?”

“There’s no way. I can’t do it.” There was so much pain. I thought that if I were moved or jostled, it would further complicate my internal injuries, bleeding me out and probably killing me.

“Turn me, Charlie,” I gasped. “Let me lie horizontal on the ledge. It hurts way too much to sit up.”

I felt like I was slipping into a state of unconsciousness. If I went unconscious, I feared that I would never wake up. I fought dutifully, diligently, to stay awake. But I felt so sick, I hurt so badly, that I thought that I was done.

[Photo] Charlie Sassara

This was it; this was the one. So this is what it’s like to slowly die, I thought. I was finally finished. I couldn’t dodge the bullet anymore. It’s over. I’m done.

I started telling Charlie things about my mother and my girlfriend Pat that I wanted him to tell them. I had never done this before, and I could tell that it disturbed him. At the same time, he was attentive, and tried to encourage me.

————————————————————————

“What are you doing now?” I asked. Charlie had been sitting quietly for a long time.

“Just thinking,” he said. “About what?”

“Oh, about how to lower you.”

He was conflicted about leaving. The illusion of control governs many of our decisions. It was difficult for him to know that he was helping me more by leaving than by staying with me on the ledge.

The satellite phone–the same phone that facilitated my departure from Aconcagua–was at base camp.

“Getting to the sat phone is still the best option,” I assured him. With no litter and with what would surely be marginal anchors on the descent, not to mention my injuries, I knew he should just go. I would deal with the consequences as best I could.

————————————————————————

The pain came in waves. I wasn’t giving up, but the tide was going out. I could feel the weakening pulse in my veins.

I swallowed a thirty-milligram codeine tablet. The pill was meager at best, but it was all we had. To save weight and bulk, I had chosen to bring twelve such tablets on the climb. They did take the edge off. Still, a little more horsepower–like the morphine IV at base camp, for example-would have been just fine. Last time for that mistake.

Once Charlie got me horizontal, he worked tirelessly, getting me fully clothed with an expedition parka, putting both foam pads underneath me and then putting both sleeping bags (we had thirty-degree synthetic bags to save weight) on top. He continued to melt water, hydrate me, and give me food.

As Charlie worked, I focused on the pain. Even though I was communicating with him, I could only hear things; I didn’t really follow what he was doing. I closed my eyes and focused: maintain, relax, find the position with the least amount of discomfort.

Then, I went to that place I had learned from the Guillian-Barre. I embraced the pain.

Is that all? Is that it? Bring it on! Breathe the pain inward. Now, let it consume you! Gain strength from the pain. Embrace it, Jack!

Pain is only fear leaving the body. Guillian-Barre had been good training for the ledge.

[Photo] Jack Tackle

————————————————————————

The next challenge was to get the bivy tent up and me inside. Leaving me unsheltered in a place like this, especially if it started to snow, was a bad idea.

Charlie pulled the tent millimeter by millimeter around me as I sat in an upright state. Once I was inside, he put the pads, the sleeping bags and all of my gear inside. He placed my pack underneath my head and hung the stove.

Charlie had melted four and a half liters of water, and he gave it to me, along with the two and a half cartridges of fuel that remained. He left all the food except for what he needed to get back to the base-camp tent.

The ledge was not very wide, and I was in a precarious place. I needed to be anchored, so Charlie placed an ice screw through the inside wall of the tent, wrapped a sling around my hips and clipped me in. Then he cut off a piece of yellow eight-mil rope, which was still tied into my harness, and ran the rope out the door of the tent to my original three-piton belay anchor.

I was reasonably comfortable, all things considered. I was in the tent; I had all I needed to stay alive for at least a week.

Charlie meticulously organized all the gear to descend. He rigged up the rappel as he talked to me about the plan.

The north face of Augusta is tight, steep terrain, and we were halfway up its 3,000-foot lower wall, with another 4,000 feet above that to the summit. The best ship for navigating this kind of ground that we knew of was the Llama helicopter. A Llama was stationed at Denali National Park. The problem was we were in Canada, in Kluane National Park, 300 miles from Talkeetna and the Llama. We both agreed we needed to call Daryl Miller.

Daryl is the chief rescue coordinator ranger for Denali National Park. A Marine, a veteran of two tours of Vietnam, a former rodeo clown and a native Montana boy like myself, Daryl is also a good friend to both Charlie and me. His vast experience with rescues on Denali, his coordination of governmental agencies and his sincere concern as a fellow climber would facilitate his ability to work out a memorandum of agreement for a cross-border operation.

Neither of us know how this is going to turn out, but I will do everything in my power to get help,” Charlie said.

“I love you, Charlie,” I said sincerely.

“I love you, too,” he replied.

He rigged his belay device into the ropes.

“Travel safe,” I told him.

“I will,” he said.

Visions of the Isis rescue flooded back into my mind as I heard him slide down the ropes.

[Photo] Charlie Sassara

————————————————————————

I knew well the objective hazards that Charlie would encounter on his descent, especially crossing the glacier unroped between the bottom of the face and our skis. Intuitively, I was supremely confident he could do it. I also understood the realities of the same hazards.

I listened as the ropes pulled softly through the snow. Then, suddenly, it was quiet. The ropes were free of the anchor, and the cord was truly severed.

I settled into my own world–just me, the inside of the tent and the pain.

It was 6:30 a.m. on Tuesday, eight and a half hours since I had been hit by the rock. My world now consisted of whatever my right arm could do. I sucked on the tube of the water bladder, keeping myself hydrated. I couldn’t really sit up. I could move my legs by bending my knees, but my upper body was in such pain that I couldn’t shift it.

Though everything was in the tent, it was very difficult to find things. I couldn’t see, or roll over, and I couldn’t use my left hand. I lost items that were a few inches away. It made me crazy.

To find out the time I would grab my left hand with my right and bring my left wrist in front of my face so that I could see my watch. It took me hours to figure out that it would be easier to take my watch off and stick it in the chest pocket of my parka, where I could reach it at will with my right hand.

Tasks that should have taken ten minutes took me an hour, which helped to pass the time. I focused on completing the littlest task. I disciplined myself to keep hydrating, to keep eating, even though my appetite was greatly suppressed by trauma.

Each hour that passed meant new chores, new little things to do. But in my mind I also imagined Charlie. I saw him rappelling. I watched him crossing the glacier over the huge slots that we had had problems getting around when we were roped. I imagined him getting to the skis and then being able to ski quickly, and perhaps even enjoyably, the couple of miles back to base camp.

I was in my own safe haven. I structured things into time segments and forced myself to do things every couple of hours, whether it be eat or drink or take my codeine tablets. I tried to stretch out the tablets by taking them in three-hour increments, but they were gone after twelve hours.

————————————————————————

In twenty-nine years of alpine climbing I had never had to be rescued. In the past, in fact, I was always on the other side, helping, putting other people in helicopters or, sometimes, in body bags. On the ledge, I never lost hope or thought that someone wouldn’t come help me. Still, the situation contradicted my entire climbing career and my philosophy of self-rescue.

Now the tables were turned. Funny how self-righteous one can be when it’s not your own ass on the line.

Two hours after Charlie left, a very important event occurred: I was able to pee for the first time. I was lying flat on my back, and I couldn’t find my pee bottle (it was in my pack, underneath my head and shoulders). In desperation, I used a big Ziploc bag. When you can’t turn over onto your side, you have to be a little creative. Most, but not everything, made it into the bag.

The results were extremely encouraging, both to my sense of optimism and to my assessment of my injuries. I expected to see blood in my urine. There was none.

[Photo] Charlie Sassara

For the first time I realized that my assumption about internal injuries was perhaps incorrect. I had never been so happy to be wrong in my life. If Charlie had known this before he left, his perspective would have been much different. He later told me that he was quite sure that I was going to die before anyone got to me. Once I peed into the Ziploc, though, I was sure that somehow I was going to make it.

————————————————————————

To observe the outside world, I needed to unzip the tent door. My restricted movement allowed me to see only the sky. Occasionally, little projectiles would come through the tent: a chunk of ice, a small rock. One stone came in right above my head, making a hole in the tent the size of a golf ball. Spindrift came in through the hole, settling on top of my face. I never took off my helmet.

I have been at altitude on Everest for long periods of time. I’ve been in six-day storms on Mount Logan, on Denali, on peaks in the Himalaya. I have the ability to hibernate. Now I hunkered down and hibernated, mentally and physically.

————————————————————————

Unpredictably, lightning bolts of pain would course through my back. All I could do was scream and curse at the top of my lungs. It was like being hooked up to the crash cart in the ER without knowing when the “Clear!” signal was coming. The bolts of pain didn’t stop during the whole episode.

————————————————————————

Late that night I heard the sound of freedom: a helicopter. It was the best helicopter sound I had ever heard. The media images of the Vietnam War during my youth and the sound of helicopters during my years of climbing had always meant something bad. For the very first time, the sound was sublime. In fact, I had never heard anything that made me happier.

Now I knew two things for sure. They were looking for me, and Charlie was alive in the tent with tons of food and the sat phone, drinking our Scotch. He had made it!

As I listened, however, I was perplexed: although distinct, the sound of the helicopter seemed very far away, and it never got any closer. It went on for half an hour or forty-five minutes, but I never had a sense that it knew where I was. Then, all of a sudden, it was gone.

I glanced at my watch. It was 12:30 a.m. on Wednesday. I knew the light became very low around midnight, and remained that way until 3:30 a.m. I surmised the helicopter would come back when the light improved.

A few minutes after the helicopter disappeared, a new sound made my spirits sink. It was the sound of spindrift falling against the tent.

I looked outside. It had started to snow.

“Fuck me in the head,” I moaned.

I have sat out some of the worst storms in my life in the Logan-St. Elias Range and it seemed like they always went on for six days. Even though I had the food, fuel and water to last that long, I felt like a tethered goat on the side of the wall. Anything falling from above would hammer my tent.

“Please, God,” I thought. “Don’t let this be a six-day storm.”

I took my earplugs out of my first-aid pouch and stuck them in my ears. I couldn’t bear to hear the constant pounding of spindrift against the tent wall. Denial can be a great survival tool.

Suddenly, something slammed into other end of the tent, ripping open a hole the size of a basketball. I was concerned about the exposed opening, but it did give me a rather novel view of the outside world. I could see the opposite wall as snowflakes swirled by. I could see water running underneath the ice on the slabs (the result of the sudden warming that had caused the rockfall in the first place). I had a new window at the end of the tent, and that was quite pleasurable. It was stimulating to my mind–and yet disturbing at the same time.

Guillian-Barre had caused nerve damage to my feet. Now, I couldn’t rub my toes or put a hot bottle against them. And I couldn’t do anything about the gaping hole. I lay watching as the tent filled up with spindrift.

When the spindrift came down through the hole above my head, I took Charlie’s parka, draped it over my head, and pretended that the spindrift wasn’t there. It was consuming the tent, pushing it away from the wall. I could feel it wedging me across the ledge, which had only been bodywidth to start. Soon, my anchors held me taut against the leaning wall of snow.

The storm lasted for six or eight hours. Intermittently I fell asleep, only to awake shivering uncontrollably. When the constant pounding of the spindrift finally subsided, I breathed a sigh of relief.

A few hours later, I heard a new sound: that of a fixed-wing airplane. I would learn later that it was an HH-C130, the sister aircraft to the Pave Hawk helicopter. The helicopter I had heard earlier had received incorrect information from the bush pilot who had flown us in; they had been looking for me on the east side of the mountain, some ninety degrees from my real location. The C130 was back to try to locate my exact position. It did so (with difficulty) and flew back to Yakutat to join forces with the Pave Hawk.

Pararescue Specialists (known as parajumpers, or PJs, for short) are highly trained members of the Special Forces. Their mandate is to rescue downed Air Force pilots in any environment on the planet. The members of the Anchorage-based 210th Squadron of the Air National Guard have been a part of civilian rescues in Alaska and climbing rescues on Denali for years. In Yakutat, three PJs from the 210th and an Air Force crew boarded the helicopter. Both aircraft headed back to Augusta.

[Photo] Charlie Sassara

————————————————————————

At noon on Wednesday, I saw the helicopter for the first time. A feeling of joy welled up inside me. I opened the door of the tent with my good hand, stuck my hand out and waved, then stuck a water bottle out to make sure that they understood that I was alive. I pulled down the pole in front of me and bent the tent inward so I could see.

An enormous rumbling behemoth hovered above. Even with my earplugs, the roar and power were unbelievable. The rotor wash was so tumultuous that I feared that the tent fabric would be blown completely off its frame, leaving me without shelter.

The rotor wash started to pick up and the din of the helicopter increased, so I zipped the tent back up. I held on to a cross member of the tent frame with my right hand and grabbed the hanging stove with my bad left hand. The vibration and the noise increased. I had no idea what was going on outside. All I could do was hear, feel and sense this huge machine above me creating tremendous force and shattering noise.

I had seen such rescues many times on Denali, so I envisioned what they were going to try to do. It was to be a longhaul rescue. One PJ would be lowered by winch on a high-tensile wire of woven steel out of the side of the helicopter as it hovered above.

I hung on to my shaking tent, blind to the outside world. The altitude and position that they were trying to achieve were severe. I would later learn that the pilot, Rick Watson, was forced to dump 1,500 pounds of fuel to achieve better maneuverability. Then, PJ Dave Shuman, the bravest man I know, was lowered 140 feet down the wire out of the side of the hovering ship. The wire started oscillating uncontrollably, with Dave at the end. The aircraft was having a hard time keeping its position because of ground resonance and winds. They were forced to abort.

The helicopter came in a second time, but again they were forced to pull out. Dave told Rick that he wanted to try it once more.

Tom Dietrich, the flight engineer, lowered Dave some 170 feet. Rick got the ship close enough that the wire touched into the snow slope twenty feet below me. The rotors were fifteen feet from the wall.

As soon as Dave hit the snow, he sprinted up to me while still attached to the wire and ripped open the door of the tent.

“We’ve got thirty seconds to do this,” he screamed.

Dave immediately clipped a locking carabiner at the end of a long blue sling to my harness belay loop. Suddenly, I was attached to a multi-ton aircraft–but I was still tied into my original anchors.

I raced to untie. As I did so, I realized that the blue sling led out of the back door of the tent. Dave had gutted the downhill side of the tent like a fish so that I could just fall out and swing into space with him. When the wire drew tight, however, I was going to be sucked out the door and through a very small opening between the back of the tent and the rock.

I untied quickly from the anchors and unclipped from the ice screw. I then unclipped from the carabiner, put it around the tent pole and clipped it back into my belay loop just as Dave signaled the helicopter.

“We’re going to have to slide down the snow a little bit,” Dave screamed into my ear. “It’s going to hurt!”

“I don’t care!” I yelled back.

He hand signaled the ship. The wire hung down from the ship, then looped back up the slope to us at the tent site in the shape of a J.

Though only half an inch in diameter, wires are rated to over 3,200 pounds. I wasn’t worried about its strength. What I didn’t know was that you cannot load a wire dynamically. I was oblivious, but both Dave and Rick knew what could happen.

When Rick saw Dave’s hand signal, he began to move, and we started sliding down the snow, with me a couple of feet lower than Dave. As we slid, Rick took the aircraft down and out at the same time so that the wire would not be shock loaded. His masterful maneuver also allowed the wire to straighten out so that we slowly swung into a straight line beneath the helicopter.

[Photo] Jack Tackle

We flew out into space clipped to the bottom of the 200-foot wire beneath the hovering helicopter. I now know what a haul bag cutting loose five pitches from the top of El Cap must feel.

I trusted the wire, Dave and the ship. The alpine bond: trust. Every one of those guys was risking their lives to save mine. A combination of gratitude and humility filled my heart.

My new vision of the world consisted of Dave’s harness and his legs. I wrapped my one good arm around his waist to keep myself upright. He wore the same kind of pants and same harness as I did. I felt an instant kinship.

Once we had stopped swinging and were plumb beneath the ship, Tom Deitrich slowly winched us up. At the same time, the starved-for-fuel helicopter gained speed and raced toward the C130.

C130s fly tandem with Pave Hawks on missions such as this, coordinating communication and serving as their flying gas tanks. When Dave was sent down on the wire the last time, the Pave Hawk had seven minutes of fuel left on board. Thus, there had been no time for Dave to protect me against possible spinal injuries with a backboard, no C-collar, no litter–just a locking ‘biner into my harness and out into space.

We winched up toward the helicopter while the helicopter raced toward the C130. A minute or two after we were inside the Pave Hawk, Rick Watson successfully docked with the C130 and started refueling. Tom Dietrich later told me that the idiot lights were flashing on the dashboard when the helicopter docked. The chopper was out of gas.

“Just another training mission,” was Rick’s comment when I talked to him about it in Anchorage.

[Photo] Courtesy of National Resources Canada

As I was swung into the helicopter with Dave, the gleeful face of a friend surprised me. It was Denali climbing ranger Joe Reichert. I had no idea he was on the aircraft. For that matter, I wasn’t to find out that it was Dave Shuman on the end of the wire until later, either. Dave and I had met casually at an ice festival two years before on the Matanuska Glacier north of Anchorage. At the time of the rescue, he was unrecognizable beneath a helmet and goggles.

Both Dave and Joe went to work, stabilizing me and checking my vitals.

“Your girlfriend Pat is flying to Anchorage, Jack!” Joe yelled. “She’ll be there not too long after you’re in the hospital!”

It was so great to hear her name and know she was coming. Gratitude and humility once again filled me.

I was in the helicopter and lying on my back. Suddenly, amid the roar and confusion, everything inside me became quiet and calm. The rest of what was going to happen to me didn’t, in a sense, matter. It didn’t matter if they gave me morphine or not; nothing mattered, actually. As I lay on the painful metal floor with the camouflaged netting above my head, listening to the still-amazing din, I knew it was over. I was going to be OK.

[Photo] Courtesy of National Resources Canada

————————————————————————

Epilogue

During his descent, Charlie had struggled to build solid anchors: they ranged from a simple ice screw to fifty-minute exercises with pins, nuts and knotted cords. The most dangerous part of his journey, however, came when he pulled the ropes. He was exposed to the objective hazards of the seracs that had scoured our approach, not to mention rock and ice fall. On the glacier, he navigated by intuition, slowing down, focusing on the shape, texture and feel of the snow, crossing the bridges on his knees. Once he reached his skis, he encountered a low-lying cloud layer that limited visibility to less than 100 feet. We had left no ski tracks to follow; Charlie moved in breaks, keeping a bearing on the summit of Logan. He reached the tent eight hours after leaving me, placed a phone call to Kluane National Park Warden Lloyd Freeze and another to his wife, Siri, then watched as the fog closed in. It did not lift for three days.

The impact of the rock had broken my neck, my back and bruised my spinal cord. The paralysis to my left arm, my chest injuries and my broken teeth occurred as a result of the fall. I tore both cartilage and intercostal connective tissue in my chest area on both sides of my sternum. I incurred severe bruising to my left shoulder as well.

I was in the hospital for six days; I then spent another five convalescing at Charlie’s before I could fly home. Still, I was able to walk out of the hospital, and three days after leaving I was well enough to rent a car and drive to Talkeetna. Back home, my recovery continued: five weeks to the day after the rock hit me, I soloed the Upper Exum Route on the Grand Teton in ten hours car-to-car.

It has been two months now since the accident. My eye wanders up the east face of Teewinot toward the summit of the Grand from my cabin deck on Guides’ Hill. The soothing summer sun warms my face as I listen to the soft winds blowing through the pines and firs. My thoughts wander back to Augusta and the passion for Alaska so central to my soul.

I reflect upon the gifts I have, my friends, my family, and upon my desire and my need to go north in the spring.

How can I not be true to myself? How can I not answer the call?

[In 1999 Jack Tackle was presented The Robert and Miriam Underhill Award by the American Alpine Club (AAC) for outstanding mountaineering achievement. And in 2005 he was awarded the David A. Sowles Memorial Award by the AAC for assisting other climbers in need of rescues. Charlie Sassara also received the Sowles Award from the AAC in 2005.

To learn more about Jack Tackle, listen to the podcast “True Grit” on The Enormocast, and check out his story “The Accidental Mentor” in Voices from the Summit: The World’s Great Mountaineers on the Future of Climbing–Ed.]