It’s 1983, and Jan Redford and her friend Rik are jumaring up a series of ropes on a rappel route that Rik and his partner fixed the day before on El Capitan. They’d planned to return to work on a route left of this nearly blank face, but Rik’s partner had to leave with short notice. Now, as Jan and Rik ascend, they drop the ropes they don’t need for the rappel–all but two–trying to finish before sunset. Jan reaches the top of the fifth pitch, then looks up. No rope. Below her, Rik makes his way up their only remaining rope. There’s no rope attached to his harness–he’s already dropped it–and neither of them brought any gear they could place as protection. With only one rope between them, they can’t reach the next anchor; they’re stuck. When Rik comes to the same realization, Redford recounts:

Rik pounded the rock with his fists till I was sure he’d draw blood. He pounded and cursed while I cringed, suddenly transported back to Munster Hamlet where my father, fueled by Scotch, and my brother by rum and Coke, had pushed each other around, screaming. Panic cut off my breathing and I needed to escape, but there was nowhere to go. We were hanging off the same bolts. I stared off into the valley and let myself detach, until I barely registered the rage spewing beside me. Tufts of smoke rose from barbecues by the Winnebagos. My stomach growled.

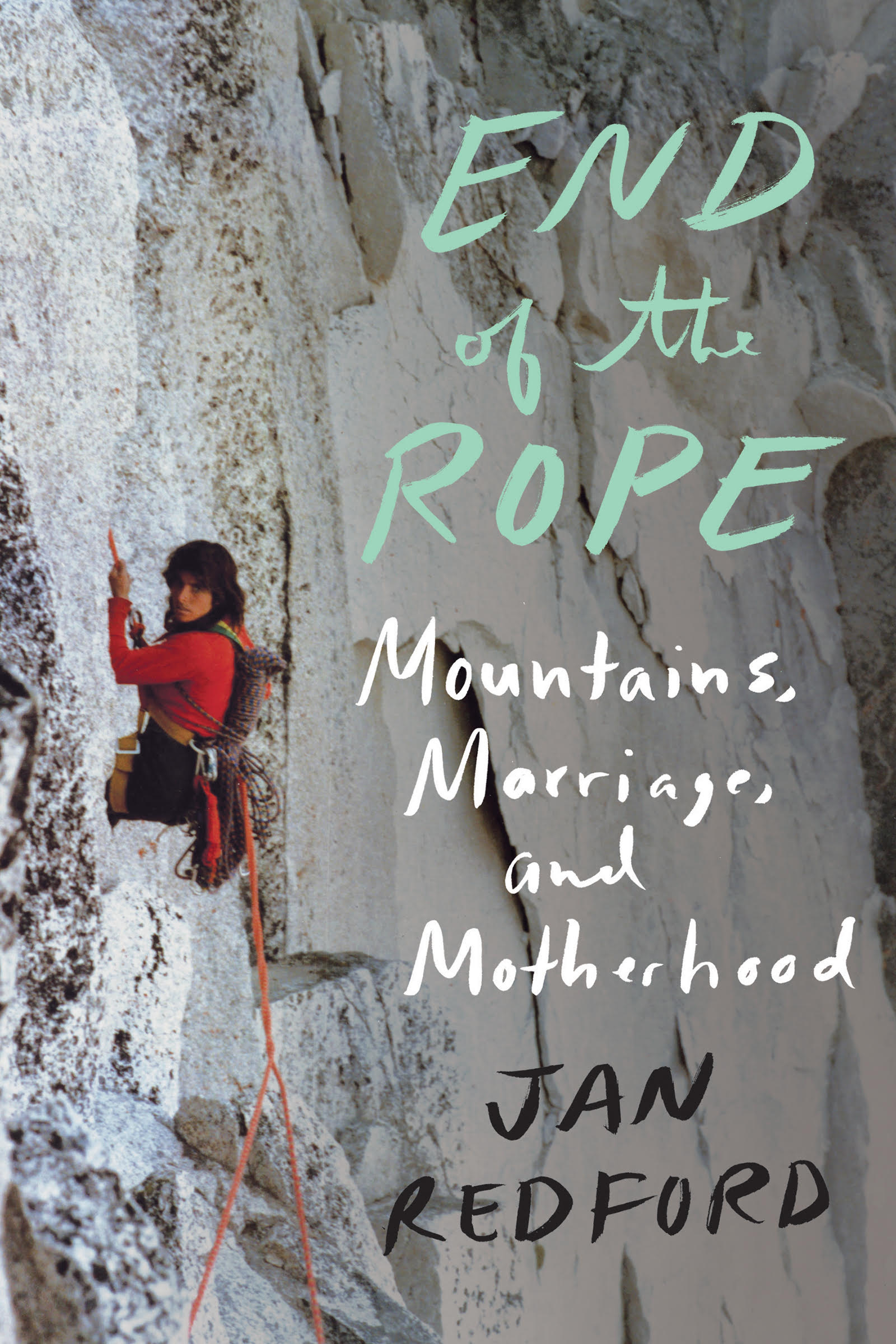

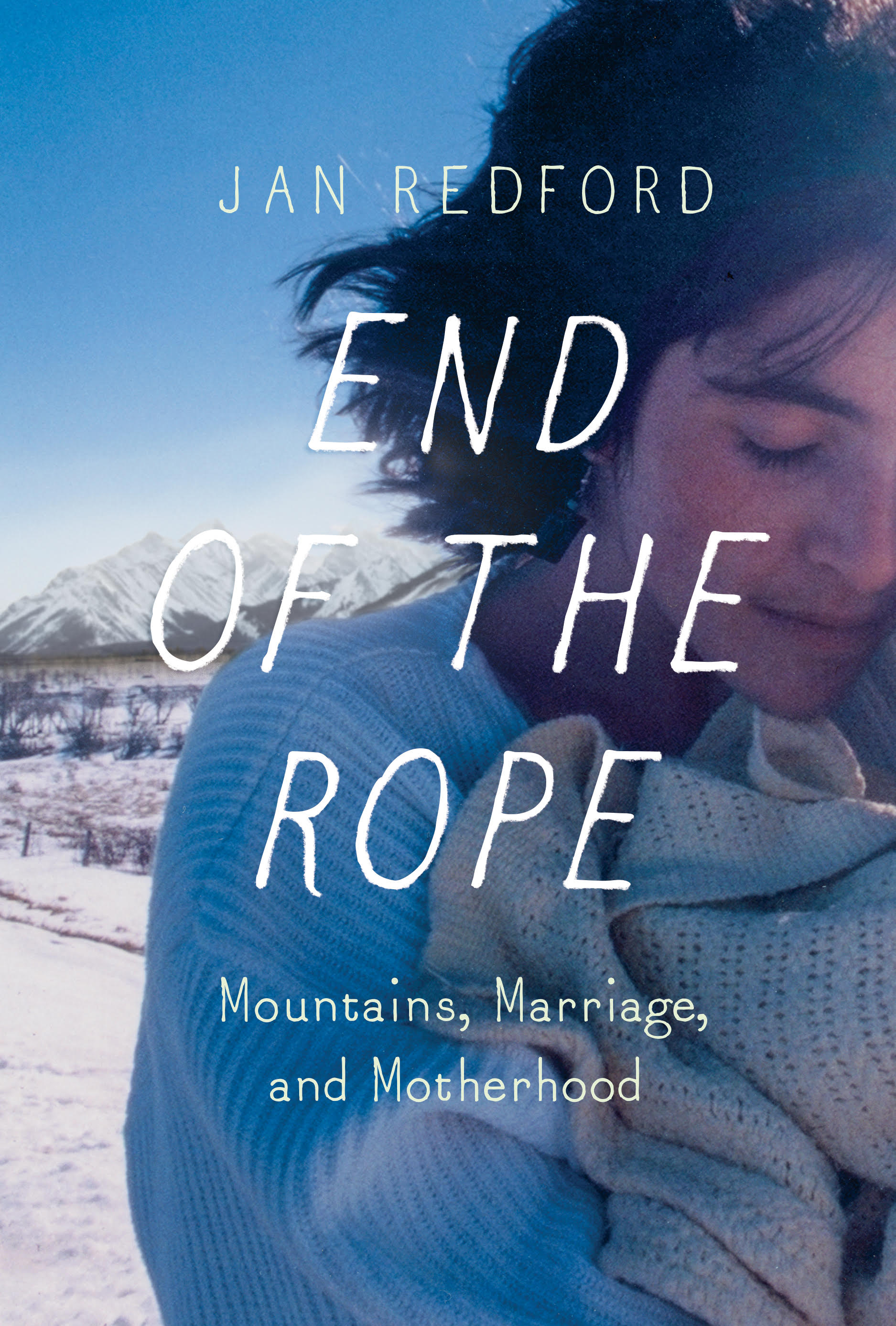

This is just one of many nerve-wracking situations Redford finds herself in throughout End of the Rope: Mountains, Marriage, and Motherhood, which was published earlier this year and is now available in hardback for $26. It is a memoir that details her young adult life into early motherhood, an era full of challenges she is able to reckon with in her own determined way.

Redford grew up in rural Canada, then left home after high school to complete a semester-long NOLS (National Outdoor Leadership School) course in the US. Thus begins her journey as a rock climber, which takes her from the Bugaboos to Yosemite, from working as a summer camp counselor to a climbing instructor for the Banff Army Cadet Camp. In industries dominated by men, she struggles to assert herself as a capable climber and independent careerwoman.

Among the book’s recurring themes are the deaths of Redford’s close friends and fellow climbers. Some are victims of avalanches; others take risks in the mountains that Redford questions, all the while knowing she’s capable of making similar decisions (and sometimes does). The funeral services–mourning family members dressed formally at the front of the church, climbers underdressed in the back–take place again and again, adding to Redford’s doubts about her own climbing. Though she wrote in her journal at the age of 14, “I’m going to be a mountain climber when I grow up,” she begins to think going to college might offer a better life than taking temporary work as a forest laborer and climbing in the off-season. When she has her own children, and everyone around her expects that she stay home to care for them, her relationship to her beloved Canadian Rockies becomes even more complicated.

Readers who’ve ever climbed with a romantic partner will find humor and truth in how Redford depicts her outings with her boyfriends and first husband. And any climber will appreciate Redford’s inner monologue as she climbs. From repeating self-help mottos to picturing her own dead body a hundred feet below, Redford depicts her genuinely riveting experiences with continual honesty throughout End of the Rope.

Ultimately, it’s the journey Redford takes–first rebelling against her family and society’s expectations, then tentatively learning to listen to and believe in herself and pursuing the potential she knows she has despite obstacles–that’s appealing to anyone interested in a good story. Redford takes us through many years, relationships and plot twists with deft clarity and lyrical language, and always with a dose of humor. Describing her separation with her husband, she says, “Quitting him was like quitting chewing tobacco or cigarettes. Needing one more drag, or one more chew, despite the threat of a gruesome assortment of cancers.”

As a young woman, Redford spends much of her time and energy worried about courage, “wishing I were half as nervy” as the people around her. It is with courage that she and Rik are able, eventually and awkwardly, to descend El Cap–rapping off “a single rusted piton… and a carabiner that Rik had wedged in [the crack] as a backup”–just enough to grab the attention of YOSAR. And it is with incredible courage that Redford pushes herself into the male-dominated spheres of climbing, guiding and forestry in the ’80s. But End of the Rope is the work of a different kind of a courage–a more vulnerable and hard-earned courage, one more open to trial and error on a climb as well as on the ground.

[Redford’s daughter, Jenna Robinson, has an art feature titled “Through the Canvas” in the upcoming Alpinist 63.–Ed.]