In 1986 Junko Tabei was in China with a Japanese women’s team to climb Mt. Tomur (7439m). If successful, they would be the first foreign group to summit the mountain, also called Peak Pobeda or Jengish Chokusu. Three of the climbers–Mayuri Yasuhara, Fumie Kimura and Tabei–worked their way up through fresh snow above Camp II.

The previous night, more than two feet of fresh powder had blanketed Mt. Tomur. “My heart sank further as I pictured that much new snow on such a steep slope. Avalanche. We were sitting ducks,” Tabei recalled. The only way to proceed, she’d decided, was to continue climbing up to safer ground. Clouds hovered low in the sky, and snow continually fell.

Tabei led, built an anchor at the base of a rocky overhang and belayed the two women simultaneously behind her. Kimura’s helmet popped up just a few meters below, almost at the top of the pitch. Suddenly, “with a distinct and unforgiving sound, the snow cracked across the slope between Kimura and Yasuhara, and the mountainside gave way.” Kimura disappeared.

The force of the avalanche tore out their anchor, tugging Tabei down the slope. “Hard snow like sharp needles hit my eyes, nose and mouth. In no time, I covered the distance that had taken us more than a day to ascend.” Believing these moments might be her last, Tabei cried out for her eight-year-old son.

Everything abruptly came to a halt. Waist-deep in snow, Tabei found herself immobilized in a twisted position. She shouted for her teammates.

Incredibly, they both emerged unhurt from the debris and ran over to dig Tabei out. Another avalanche could happen in no time, Tabei knew, so she implored them to abandon their packs along with their expensive new tent. As they rushed down, unencumbered, the next avalanche hit, knocking them over and tossing them with powder. Again, the three climbers emerged and continued their push down the slope. And again, another avalanche.

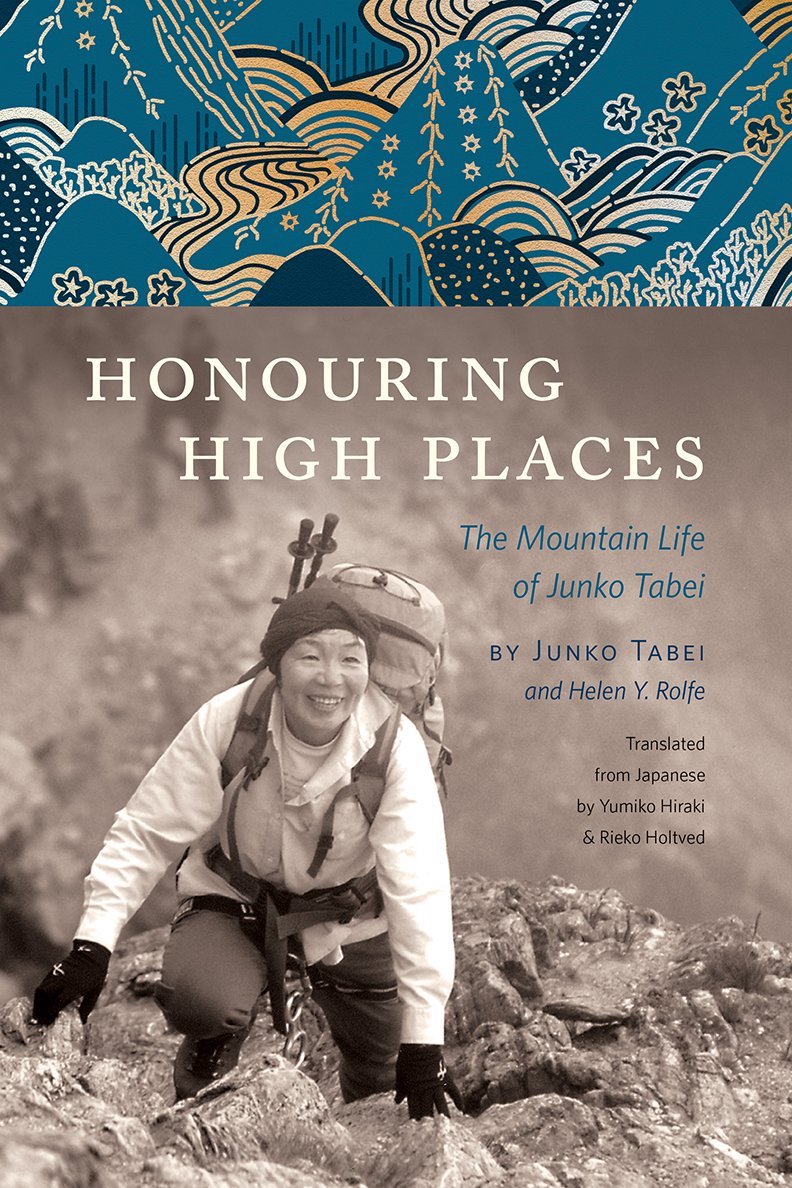

Tabei admitted, after a fourth avalanche destroyed their camp that very night, “More than a decade passed before I had recovered from the fear that engulfed me on that trip.” This refusal to sugarcoat her experiences in the mountains she nonetheless loved becomes a main theme throughout Honouring High Places. Now available in hardback for $32, this collection includes many scenes and stories taken from several memoirs Junko Tabei wrote before her death from cancer in 2016.

This book is remarkable for several reasons: among them, this is the first time the English-speaking world has seen a full-length book from the first woman to summit Chomolungma (Everest). Before Chomolungma, she was the first woman and first Japanese climber to ascend Annapurna III. And in 1992, Tabei became the first woman to climb all Seven Summits, the highest peaks of every continent.

Her achievements as a climber seem even more extraordinary after you read the stories behind them. Though Honouring High Places begins on Chomolungma in 1975, it quickly shifts in the second essay to describe Tabei’s upbringing in Fukushima Prefecture. Her father was initially disappointed to have a fifth daughter–after she was born, “he had said, ‘A girl again…'”–but he encouraged her to work hard in her studies in order to obtain a college education. Though she described herself as an unathletic child, Tabei felt astonished by an overnight field trip she took to the mountains with fellow students and their fourth-grade teacher, Watanabe-Shuntaro-sensei:

All around us, sulphur-stained holes in the ground sizzled where natural onsen came to life at our feet. I admired the juxtaposition of the heat from the springs and the cold temperatures (despite it being summer) on the mountain. The impact this had on me, the effect on my body and skin, was unforgettable. It trigged an awareness that there were many things in the world for me to discover.

Descriptions of the alpine landscapes Tabei explored are unfailingly keen and joyous, words that seem apt for the kind of person she was, even amid adversity. “It was unusual enough to be a female climber in that era of yesteryear,” she recounted. Her laser focus on climbing meant she didn’t have time for dating, which worried her family, from whom she long kept her passion for mountaineering a secret. She later met her husband, Masanobu Tabei, through climbing, after much handwringing by her mother, who once criticized, “You are already twenty-six and not married.”

After accounts of her early adulthood, the book proceeds with each subsequent essay detailing a different expedition until Junko Tabei falls ill with cancer, at which time she refocuses much of her efforts on charity work.

Honouring High Places doesn’t shy away from depicting the challenges of expedition leadership. Though Tabei’s international travels as a mother of a daughter and son, Noriko and Shinya, proved difficult logistically and emotionally, Tabei was proud of the example she set for other women by demonstrating that there can and should be space in life for both one’s passions and one’s family. At times, she found the tensions on expeditions challenging. For example, she and the Ladies Climbing Club of Japan chose, after summiting Annapurna III, to be forthcoming about their disagreements in their 1973 book Annapurna: Women’s Battle:

Over the years, I had heard many male-only expeditions tolerate unfriendly incidents, like someone having his teeth broken because he was hit by a teammate, a climber stamping his crampon-clad foot on another climber in rage, or loud verbal arguments between leader and team members dispatched over the radio. Yet, when the trip summaries were published, not a word of such stories was written. I find there is a vanity to that kind of presentation. It saddened me….

Though there are many lessons to take away from Tabei’s life, perhaps the most important is not just how and what she climbed, but also how and what she accomplished as a mountaineer when she wasn’t climbing. In 1969, she founded the aforementioned Ladies Climbing Club in Japan, and she later established other women’s outdoor groups as well. Concerned with the growing environmental crisis in the Himalaya as a result of climbers and tourists, Tabei was the chairperson of the Himalayan Adventure Trust of Japan for nearly a quarter century, and completed her master’s degree “in social culture with my focus on the garbage problem in the Himalayas” in 2000. Over the years, she gave numerous speeches and helped to organize many events across Japan, including the ongoing Mount Fuji for the High School Students of Tohoku Earthquake hike, where students affected by the 2011 earthquake and subsequent nuclear disaster in Fukushima ascend Mt. Fuji, the highest peak in Japan, together every year.

The book concludes with remembrances written by her friend and climbing partner Setsuko Kitamura; her husband, Masanobu Tabei; and her son, Shinya Tabei. There is also an impressive and useful timeline of Junko Tabei’s life, including all her major climbing accomplishments.

The publication of Honouring High Places in English is not only significant because of Tabei’s successful ascents, but also because of the in-depth look it gives us into the struggles and possibilities of a climbing life: from confronting the avalanche-prone alpine realm to planning expeditions as a parent, to raising environmental awareness and trying to prevent further ecological catastrophes. Junko Tabei relied on her own intuition, honed her ability to listen to herself and learned to appreciate all aspects of “high places,” including their challenges. Honouring High Places is an admirable testament to the determination it takes to love “unforgiving terrain”–which she admired on Chomolungma and all over the world–for a lifetime.

The book is a finalist for the Banff Book Competition’s Mountain Literature-Non-Fiction Award. The other finalists in all categories can be found here.