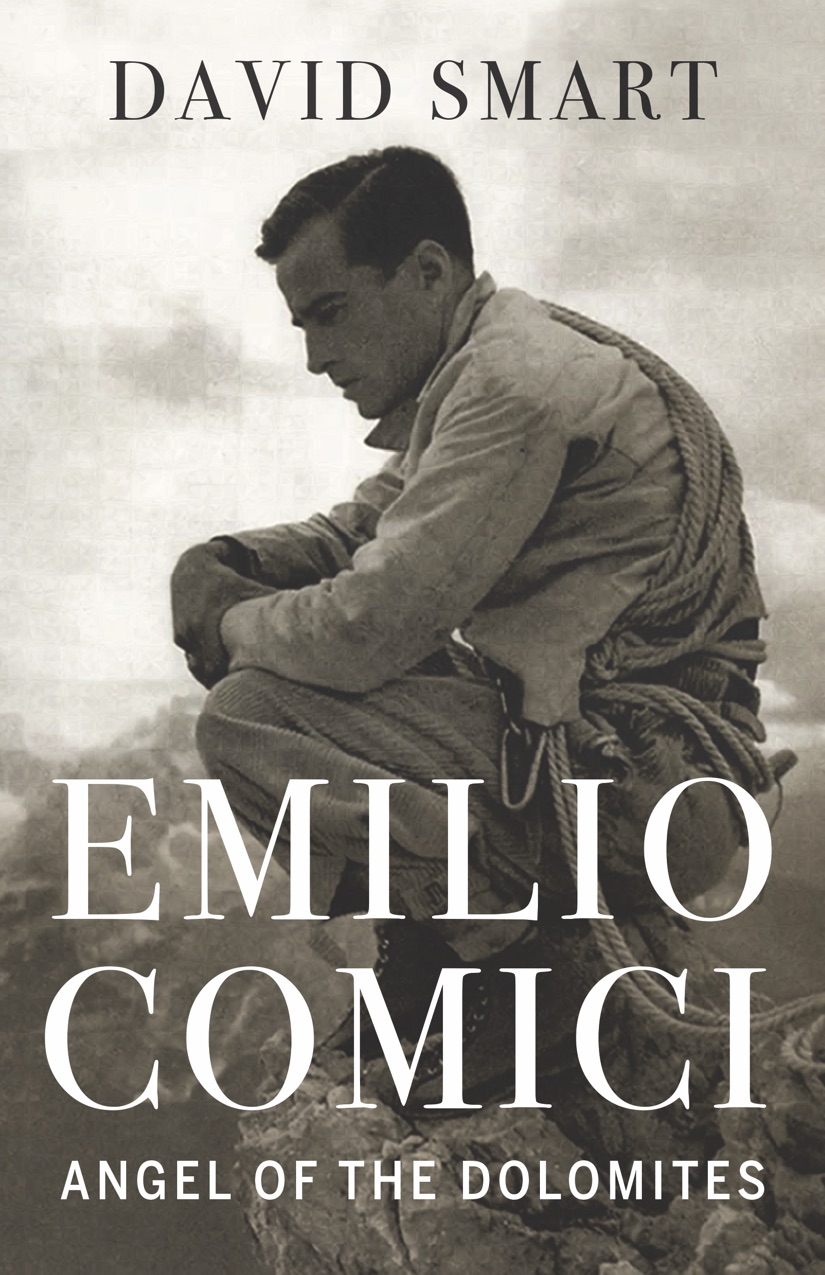

David Smart’s book, Emilio Comici: Angel of the Dolomites, received the Boardman-Tasker Award for Mountain Literature in November. The biography was published in 2020 and provided some of the inspiration for Smart’s Mountain Profile on the Cima Grande in the Dolomites that was recently published in Alpinist 76.

The following Q&A between Alpinist Digital Editor Derek Franz and Smart explores topics related to Emilio Comici: Angel of the Dolomites, the Cima Grande profile and Smart’s writing and climbing career.

Is my perception correct that the idea for a Mountain Profile on the Cima Grande materialized following your work on the Comici book?

Yes, it did. There was so much to say about the mountain and the region before and after Comici’s time there, that I wanted to tell a broader story. The Cima Grande has been the crucible of so many developments in climbing, and the place where so many important figures have proven themselves, pushed standards, certainly, but also picked up or developed new ideas about climbing.

![emilio-comici-book-4 The Tre Cime di Lavaredo (Drei Zinnen) in the Sexten Dolomites of Italy: the tallest peak in the left cluster is the Cima Piccola (Kleine Zinne, 2857m); the Cima Grande (Grosse Zinne, 2999m) is in the middle; and the Cima Ovest (Westliche Zinne, 2973m) is on the right. [Photo] Adobe Stock](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/emilio-comici-book-4.jpeg)

When did you first take interest in Comici’s life? Was it before or after visiting the Dolomites?

I can’t remember when I first heard of him. Probably when I read Doug Scott’s book, Big Wall Climbing, in the late ’70s. His history of climbing in the eastern Alps remains the best comprehensive treatment in English. [Scott] told me that the history of climbing there was one of his areas of special interest, and he had many. I only visited the Dolomites years later, in the late ’80s. It certainly piqued my interest in the early days there, and Comici’s name was everywhere.

In the Mountain Profile, you write about learning to climb as a young man on limestone cliffs in Canada (in Ontario and the Rockies). You write that “the legacy of the Dolomites was everywhere around me,” and how European immigrants brought their knowledge and skills from the limestone in the Alps. Is it safe to say that you felt curiosity and a connection to the Dolomites since you started climbing?

Almost. Yosemite was considered much cooler when I began to climb, and I began on limestone, first on the Niagara Escarpment, in Ontario, and then on much bigger, but similar cliffs in the Rockies. In both areas, the first modern rock climbs were done by people, and sometimes the same people, who wore knickers and hardhats and carried piton hammers and had names and climbing styles that came from alpine Europe. At first I was dismissive. They looked ponderous and outdated in their approach compared to the swami-belted Stonemasters who were the template for teenage climbing at the time. But I was also curious and learned over time that they came from a much longer tradition of hard climbing than that of Yosemite.

![emilio-comici-book-3 Emilio Comici. [Photo] Courtesy of Rocky Mountain Books](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/emilio-comici-book-3.jpg)

You also wrote a book about Paul Preuss, which was a contender for the Boardman-Tasker and Banff awards in 2019. It seems to me that there is some overlap between Preuss and Comici as far as their climbing philosophies are concerned–I’m guessing that the philosophy of bold, clean free climbing is the first thing that got your attention and inspired you to learn more about these men? Can you tell me a bit about how you came around to doing these book projects, and the personal connection you seem to have with them? (I imagine you must have a deep personal connection to the material, judging by the award-winning results!)

Preuss was a towering figure in the history of climbing, but there was little of quality in English, so I wanted to introduce him to an English audience. As I got to know him through research, I found him compelling on a personal level. Certainly, his boldness was absolutely unprecedented. Comici is really the next monumental figure after Preuss, although by no means the only great climber of his era. After Comici, many things happened in the Dolomites, but the next great figure for me is Royal Robbins. I am writing a book about him now, which is wonderful. There are a lot of materials. A single hard-drive put together by his daughter Tamara contains 46,000 items. The course of a human life is a basic unit of storytelling, tens of thousands of years older than hero’s journeys and such-like. We all understand and relate to a life because we all have one, so it’s a wonderful medium for telling the story of climbing.

At what point did you know that you wanted to be a writer/publisher? Has your writing been mostly focused on climbing topics? (It seems that for so many of us, climbing and writing go hand-in-hand, and I suspect a lot of it comes back to reading climbing books as kids and being inspired by both the activity and the inspiration we felt through the written word. Is that the case for you?)

I always was a voracious reader, often, as a child, obsessed with obscure topics like Victorian submarines or French sub-Saharan Africa. My mother used to make fun of me by asking where Lower Volta was. So in a way, I was primed for climbing literature’s legends, histories and other nooks and crannies and obscurities. In university, my professors would criticize my papers because they “seemed too much like magazine articles,” which always baffled me but turned out to be prescient. I wrote magazine articles for Climbing and the Canadian Alpine Journal, several guidebooks for Ontario rock climbing, then a memoir, A Youth Wasted Climbing, and two historical novels, Above the Reich and Cinema Vertigo, before the biographies. I owe a lot of my success with books to my publishers, Don Gorman at Rocky Mountain Books and Jerry Auld, who helmed the now-shuttered Imaginary Mountains Press.

This Mountain Profile was initially planned for a later issue. Barry Blanchard was working on another one for us, but then he had his very unfortunate accident and his project had to be put on hold. How did you manage to turn this article around on such short notice–what was the process?

I had a version of it ready, or what one thinks of as ready before working with Paula LaRochelle and Katie Ives. It was my second big piece in Alpinist, and I always marvel at their talents as co-conspirators, improvers, and hard workers. Thanks to them, we went from a very rough piece to a very complete one quickly. It was also nice to be able to fill in for Barry, although I wish it had been in better circumstances for him.

What does it feel like to have your book recognized with the Boardman-Tasker?

Pretty amazing but unexpected. I started watching late and before the end of the show Ian Welsted texted me to congratulate me, then Jon Popowich did the same, but I thought it was just for being shortlisted. What a surprise.

Are you still very involved with Gripped magazine as its co-founder? What’s it like to juggle those duties with the books?

Yes, I’m the editorial director at Gripped Publishing. We publish four magazines: Canadian Running, Canadian Cycling, Triathlon Magazine Canada and Gripped. Most of my writing is done very early in the morning or other times. I can write anywhere, any time, and I enjoy it. I love working with staff from other sports than climbing.

![emilio-comici-book-2 David Smart. [Photo] Courtesy of David Smart and Rocky Mountain Books](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/emilio-comici-book-2.jpg)

[More information about Emilio Comici: Angel of the Dolomites can be found here. You can learn more about Alpinist 76 and the Mountain Profile in our online store here.]