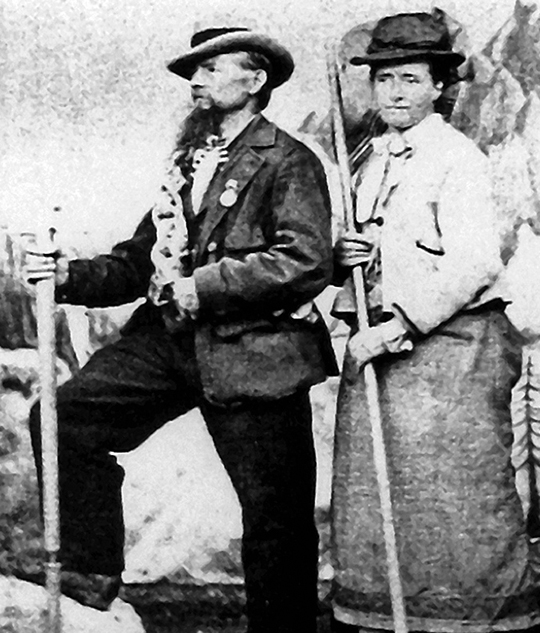

[Photo] Courtesy Claude Gardien

SEPTEMBER 22, 1871, WAS ONE of those magical autumn days, when your gaze pierces farther than usual across the crystalline air. Mists had already consumed the valleys, obscuring most signs of human presence–apart from the occasional plume of distant smoke that rose straight up. There wasn’t even a breath of wind. Two British women, Emmeline Lewis Lloyd and Mary Isabella Straton, stood atop the Moine, a 3412-meter granite pyramid that faces Mont Blanc and the Grandes Jorasses. Joseph Simond and Jean-Esteril Charlet, both Chamonix guides, accompanied them on this first ascent. Their route had led them over one of the most beautiful belvederes in the massif, across sunny granite into a universe composed entirely of glaciers.

Charlet’s gaze sparkled with playfulness and goodwill. He had an elegant goatee. Miss Isabella was not insensible to his charms. Very much at home in this landscape, wearing the long skirt and hat without which no lady could be seen climbing a mountain, she watched him from the corner of her eye–discretely. Summer followed summer, and she kept returning to her guide and completing more climbs, including new routes in the Mont Blanc massif. And thus in 1875, an aiguille of 3761 meters, near Triolet, became the Pointe Isabelle.

In January 1876, the guide and his client set out into the heart of the cold to make the first winter ascent of Mont Blanc. Quite a feat, if you think of the equipment of the time: layers of ordinary heavy clothing that made it hard to move; rudimentary gloves; boots without any modern form of insulation, just an extra pair of socks. The air was icy, and Isabella’s fingers became numb. They soon found a remedy: rubbing them well with cognac and snow! From the summit, the party gazed out upon mountain after mountain enfolded by white slopes and blue shadows. The valley of Chamonix seemed frozen solid. Snowdrifts extended to the vanishing point, covering all traces of green, as if the Alps had transformed into a polar landscape.

That same year, Miss Isabella remarked to her guide that they’d been spending so much time together and they’d come know each other so well that they need never be apart again…. Charlet hesitated. His client was a rich heiress who had lost her parents. He was a poor man who had herded animals before becoming a carpenter, a porter and finally a guide. He loved the mountains too much to renounce them. But Miss Isabella wasn’t asking him to hang up his ice axe. “In that case,” the timid guide responded. “I must ask if the regulations allow it.” The Compagnie des Guides de Chamonix had nothing in their rules about such a case. And so it was that Jean-Esteril Charlet and Isabella Straton married on November 28, 1876. It was a magnificent wedding: sixteen horse-drawn carriages formed part of the procession.

Charlet remained an audacious climber. The most extraordinary aiguille, the one dominating the entire valley, obsessed him: the Drus. In 1876 he tried to climb it by himself. “If I have not returned by the day after tomorrow, it’s because I’ve taken my last tumble,” he announced to a friend. Charlet climbed very high on the Charpoua side of the Petit Dru. At the base of a smooth wall that he didn’t dare confront alone, he glimpsed the broken rocks upholding the Breche des Drus between the two summits. Above that wall, undoubtedly, the difficulties would be over. He stuck a flag in a crack and descended. For the first time in his life, he imagined a technique to descend by the rope: the “rappel,” already used by Edward Whymper during a solitary attempt on the Matterhorn. After a miserable bivouac in the Charpoua basin, Charlet arrived at Montenvers, his limbs stiff with cold, his clothing torn.

In 1878 Clinton Thomas Dent, James Walker Hartley, Kaspar Maurer and Alexander Burgener achieved the first ascent of the 3754-meter Grand Dru. Dent, who had made eighteen previous attempts (including one with wooden ladders), cast doubt upon Charlet’s tale. Charlet wanted to prove that he hadn’t lied. Furthermore, he considered the Petit Dru to be the more important of the twin peaks, because its summit could be seen from Chamonix. And it was more difficult.

On August 28, 1879, Charlet returned with two friends: Frederic Folliguet and Prosper Payot. Isabella didn’t want him to leave by himself. Retracing Charlet’s previous route, the party bivouacked on a pinnacled ridge, and then reached the summit of the Petit Dru at 8 a.m. From the valley, spectators watched them through lorgnettes. In accordance with local tradition, a cannon thundered to salute their first ascent. Years later, this original route would remain the ideal line of acent for the classic traverse of the two summits.

Jean-Esteril and Isabella Charlet-Straton settled in Argentiere and made several first ascents in the Aiguilles Rouges. They led a happy family life with their two sons, who both became climbers. One of them, Robert, died on the frontline during World War I. In their old age, Jean-Esteril and Isabella moved to La Roche sur-Foron, a little town downstream from the Valley of the Arve. Isabella died in 1918, Jean Esteril in 1925. A grandchild founded a hotel in Chamonix, the Hotel Pointe Isabella. It still exists, and only a short time ago, it was still run by a descendent of the couple. But their history is rarely told. Many alpinists have raised their gaze toward the Drus, hoping to climb them one day. How many of them know that the first ascent of the Petit Dru is part of one of the most beautiful stories in alpinism, and that it’s also a love story, a fairy tale in which the shepherd marries the princess?

–Translated from the French by Katie Ives