A flip through any edition of Accidents in North American Mountaineering reveals page upon page of incident reports that are both story and lesson, equal parts engrossing and instructive. They are a complex anthology of the climbing community’s mishaps. The annual journal, in print since 1948, acts as a reference for each year’s noteworthy accidents. A young climber falls 30 feet in Rocky Mountain National Park and dies; an adequate belay anchor might have saved his life. An experienced, unroped man is swept down steep terrain by an avalanche; his excitement may have outweighed his awareness of the objective dangers. From their experiences, we learn and, hopefully, gain a more comprehensive understanding of our limits as climbers.

For the last four decades, one man has worked as the editor of Accidents, compiling reports and writing unbiased, detailed analyses for the betterment of the community at large. “Forty years, a nice even number,” John “Jed” Williamson reflected about his retirement from the journal in his interview with Alpinist.

Throughout his time as editor, Williamson worked solely as a volunteer, donating an estimated 5,000 man-hours. But what’s special about Williamson’s work with Accidents is more than the tidy numbers. “I try to find the truth of the matter,” a soft-spoken Williamson said.

Before his start with the publication in 1974, Williamson was already an enthusiastic member of the growing North American climbing community. In the summer of 1960, he joined Bill Putnam in the Northern Selkirks for his first-ever expedition. “We did about as much bushwacking as we did climbing,” Williamson said of the trip in a 2008 interview with the American Alpine Club’s Gary Landeck.

Two years later, while attending graduate school in Alaska, Williamson was a member of a team that climbed Denali via a new route after Brad Washburn told him, “You boys climb this route here, it’s called the East Buttress, and it has not been climbed.” Williamson was drafted into the US Army shortly after his return from the ascent.

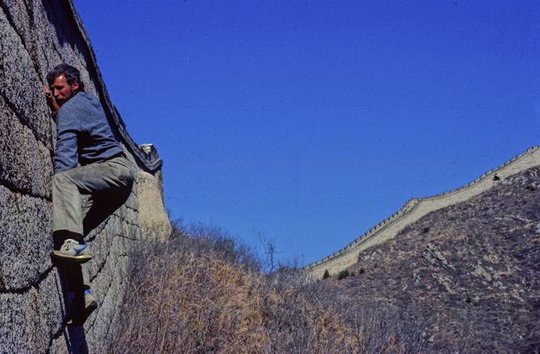

Over the next five decades, Williamson snuck in expeditions while establishing himself as an active and respected voice in the outdoor community. He worked with NOLS, the Student Conservation Association, the Association for Experiential Education and a host of other organizations, co-founding the Wilderness Risk Managers Steering Committee and serving as the president of Vermont’s Sterling College. This year, to celebrate his 75th birthday, he climbed the Grand Teton.

Though Williamson is stepping down as editor after 40 years of service, he will remain as an advisor and is already planning a new undertaking. “I started a project awhile back looking at significant accidents over the course of the years,” Williamson told Alpinist. During the later few decades of his Accidents tenure, he made note of particularly important incidents, and hopes to compile them. “I’m thinking about making something like After the Fall: Hard Lessons in Mountaineering Come to Life.”

Chatting with Williamson by phone as his last edition of Accidents debuted, he told Alpinist what lessons he has learned from the mistakes of others, what it means to be a climber and how to give back.

You started out as the volunteer editor of Accidents in North American Mountaineering 40 years ago, and you’ve been doing the work pro bono all this time. What motivated you?

Well, everybody needs to do some kind of service. I was asked by Bill Putnam and Ben Ferris. Ben was the first editor, who by coincidence I had been on my first expedition with back in 1960 to the Northern Selkirks. Back then [the book] was a slimmer volume and a little bit of an easier job. It was all [done by] typewriter. You ever use one of those? Then things got a little more complicated, but I was into it. I knew a lot of the land managers and had some ins, so I just kept doing it. I said to myself, This is a good thing to do.

They ask me how long it takes me to do it each year, and I estimate between 100 and 150 hours, depending on what’s going on, whether I have to go back and talk with people who are in the incidents. It’s a service project. I have kept a consistent path on the whole thing. I try to find the truth of the matter.

What trends do you see in the type of accidents occurring and the causes behind them?

I didn’t see equipment failure in the early days. The primary cause of accidents in my early days [as editor] was that people started taking leader falls. The rule when I first started climbing was that the leader doesn’t fall. And now, you’re not really pushing the edge unless you do fall.

Of course we also have an increase in climbers. When I started [in 1974] I think there were 400 members of the American Alpine Club and maybe only 500 climbers in the US. Today, my estimate is around 300,000. [Research about the outdoors] says millions, but I don’t believe it. I know how many climbers visit the Gunks, I know how many climbers visit Hueco Tanks, I know how many climbers visit Rainer and the Tetons. No matter how I shuffle the numbers I can’t get anywhere near a million.

I also believe it’s a conversion [problem] from indoor walls to outdoor climbing. We see, despite all our efforts, a number of rappel mistakes, and we still see a number of lowering mistakes. You know, that’s so basic. It’s hard for me to understand why climbers don’t pay attention to that right away.

And of course equipment has changed. With the addition of more technical and complicated equipment, such as loaded cams and what not, we start to see an increase in protection pulling out. Pitons didn’t pull out so much. One of the sidebars on that is that a lot of people bought [expensive] cams didn’t want to put them in so far that they couldn’t get them out, so that was part of the problem.

There really isn’t equipment failure anymore. Ropes don’t break, it’s rare that a cam or a carabiner breaks, and when they do it’s usually because the gate on the carabiner comes open because they fastened it incorrectly. So equipment pretty much doesn’t break, it’s all got to do with the users.

What roadblocks have you encountered during your years as editor?

It’s getting harder for us to get names and addresses from the parks now. Some are refusing to do it. Because of HIPPA. And there are some people who of course just don’t want to report. And we say look, if there’s a lesson to be learned why not include the lesson and we’ll exclude your name? I’ve been trying to not place blame from the beginning. I try to let the incident speak for itself, so that little or no analysis is necessary. If we write an analysis it doesn’t begin with, “This guy was an idiot.”

When possible, some of the best accident reports have been the ones that have come from individuals. They may think that they’ve done something stupid, but it’s ok for them to say that. They might come out with something like, “I was totally distracted that day, I should never have been climbing.”

How did writing Accidents for 40 years change you as a climber?

Yeah, gee, I just don’t go outside anymore, it’s too frightening [laughs]. It certainly upped my awareness level. But the change that it brought about for me was that my name was out there as someone who was doing this kind of work. I got involved at a deeper level.

How do you decide what mountain accidents to cover? Where do you draw the line between what’s climbing and what’s not?

I’m very specific about that. First of all, we say three points of contact. So that eliminates hiking. Second of all, it involves terrain that is more than just people without ropes on fifth class terrain. And they must engage in the act of climbing, rock or ice or mountaineering more than 10 days a year. It probably should be even higher than that. Malcolm Gladwell says you’re not going to be doing something well unless you’re putting in 10,000 hours. So that means people who are guided may only put in a short period of time. They do difficult stuff, but are they climbers? Well, only if they continue the sport on their own.

And what about gym climbers?

Well, I’m glad gym climbers are there, because I don’t have to put up with them. You know, that’s thousands fewer people cluttering up the mountains that I love. And I’ve been known to go to a gym because I’d rather do that than lift weights.

Do you see a higher frequency of accidents among climbers who learned on an inside wall and are now taking their skills outdoors?

Yeah they haven’t learned about placing protection, placing anchors, and they’re lowered all the time. If I had a rule for gyms it would be that you can’t be lowered, you have to downclimb. Boy, wouldn’t that slow things down? When I learned to climb one of my mentors said, “You’ve got to climb down everything we climb up.”

I asked Alex Honnold, “Alex, do you think you could downclimb the stuff you go up, in case you get in trouble?” And he said he really wouldn’t do it in unless he could downclimb it.

What do you want the climbing community at large to take away from this contribution that you’ve given it?

Well, I’ve said from the beginning that we all have to decide on some kind of consistent service that we provide and you know, it could be less glamorous, such as being an inner city school teacher or whatever, but if you’re going to take from the world that you love so much, you’ve got to think about ways to give back to it. So I encourage people who are outdoor enthusiasts to enjoy what they have but to think about ways to give back.