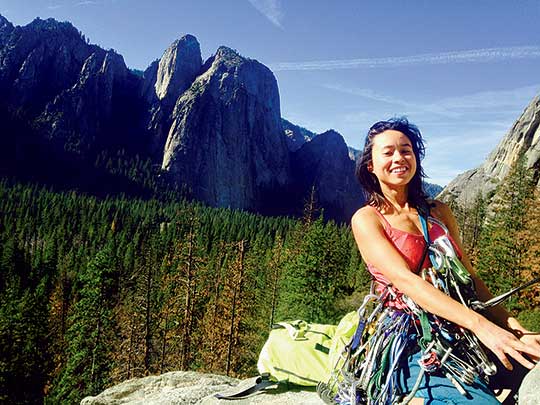

[Photo] Rex Lu

FAY PULLEN REGARDED THE CRUX OF THE WEST RIDGE OF PRUSIK PEAK IN THE CASCADES: a large slab of smooth, white, indifferent granite. There was only the sound of the wind and her breathing. She gripped a palm-sized skyhook in one hand. “I knew that pitch would give me trouble,” she later recounted, “so I came prepared.” Each time she threw the hook upward, she listened for a reassuring thud and then pulled on the rope to test the placement. Eventually, she struck the right combination of trust and fatigue. With this makeshift, uncertain belay, she continued to the summit. Far below, the Enchantment Lakes shone a richly saturated blue. She felt lucky to have such a classic route to herself.

————————————————————————

Now seventy-three years old, Fay spends most of her time in the mountains. As part of a family of Cascades climbers, I grew up reading her meticulous trip reports. In my late twenties, searching for my own path as a woman and a climber, I remembered that Fay had explored the hills alone for decades, free from the tangled expectations of gender roles. I decided to seek her out.

Fay lives in a small house in the woods on the outskirts of Seattle. One December evening, my feet slipped up her steep dirt driveway in the freezing rain. Shadows of evergreens loomed in the dark. A petite, white-haired woman opened the door, smiling. Inside, her oil paintings gleamed with snowcapped mountains. A Christmas tree twinkled with well-worn ornaments, left over from when her two children were young. Colorful ropes, jackets and cams filled the bedroom and laundry room. She apologized for the amount of equipment: “It’s just that they keep coming out with lighter and lighter gear.”

[Photo] Madeline Coburn

Fay had started going on solitary trips at age twelve. “Just me and my dog in a pup tent,” she said. “I wanted to go, and there was no one else to go with.” As a PhD student at the University of Washington, she was drawn

to the Cascades. But she didn’t find a sense of belonging in the male-dominated mountaineering world of the early 1960s, so once she learned some

basic skills, she started soloing. Her most intense climbing began after she became a widow at age sixty. “I used it as therapy,” she said. Today, she worries that she could injure herself if she tried to keep up with younger partners. “I do so much better if I go at my own pace.”

In 2000 local mountaineer John Roper was resting below Mt. Constance when he and a friend noticed a solitary figure descending a snow gully. Intrigued, he invited the climber to join them. Fay had just summited Inner Constance, via a “crumbly, Class 4” route–part of her dream to climb all the mountains in Washington. So far, she has stood atop 196 of the state’s highest 200 peaks. She has spent many days bushwhacking in damp forests, struggling through thickets, wading across deep streams and clambering over unstable snowfields and steep ice. She has reached obscure and unnamed summits deep in the backcountry, sometimes with no trace of previous passage.

“These days, first ascents are rare, hard to prove and not really important to me,” Fay explained. “Truthfully, any peak I solo with no information (other than a map), where I have to figure everything out myself, feels like an FA to me.” As John pointed out, Fay has a level of determination that only the most committed alpinists share. She can count on one hand the times she’s turned back. Occasionally, she ropes up with a partner for difficult pitches, but she tries to avoid requiring help. She describes the mountains them- selves as her friends.

While we chatted in her house, my gaze drifted to her small hands clasped solidly together on the table. “At this point in my life,” she said, “I only have so much time left, and there’s so much

more to climb here, still.” I asked Fay what she hoped to find on those remaining summits. She grinned. “I don’t know. I’ve just got a defect in my brain, a chip that tells me to keep putting one foot in front of the other uphill until I can no longer go uphill.”

Alpinist is available to subscribers, on newsstands and for digital download with our iTunes app as well as at the other popular digital newsstand apps Zinio and Nook.