[This story originally appeared in The Climbing Life section of Alpinist 72, which will soon be available on newsstands and in our online store.–Ed.]

![a72-meditations-of-a-dreamer-1 The Pearly Gates on Mt. Hood. [Photo] Maurico Portillo collection](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/a72-meditations-of-a-dreamer-1.jpg)

July 25, 2019: I shivered in the predawn chill. At 10,000 feet on Mt. Rainier (Tahoma), Camp Muir is one of the more luxurious base camps, outfitted with fully functional toilets, guide shacks and a climbers’ hut. But my younger brother, Ricky, and I had opted to sleep outside in our bivy sacks for more of a real mountain experience. He’d complained about the cold on the way up, so I knew he was freezing, too. As I struggled in my sleeping bag to reach my water bottle, I wrestled with doubt. I’m not supposed to be here, I thought.

YOU CAN DRIVE ACROSS THE LAND of my birth, El Salvador, in four hours. It’s so small that local people nicknamed it “El Pulgarcito” (little thumb). But numerous factors, including a corrupt government, have impoverished the country and flooded many of its neighborhoods with gang violence. In search of better opportunities and a safer place to raise a family, my parents left for the US when I was four years old. I grew up in Washington State, speaking both Spanish and English. Pupusa, the national dish of El Salvador, remained a staple of my childhood: a flatbread stuffed with cheese, beans, chicharron (pork) or all three, which is my favorite kind. (Pupusas make the best summit food if you ever get the chance.) El Salvador itself seemed like a dream that occurred in my infancy. I had little recollection of the actual place.

Throughout my youth, I pursued my vision of the American Dream instead. Most of my life was shaped by the need to fit in and not reveal that I was an undocumented immigrant. I began to play organized sports as soon as I could. At age ten, I was drawn to American football. I saw the sense of national pride that others took in it, and I wanted that feeling for myself. I also longed for the mountains of my backyard. Through my bedroom window, I could glimpse the famous shape of the “elk head,” outlined in rocks and snow like a giant magical creature, below the apex of Mt. Rainier. The pale summit shone like the threshold of another world, luring my imagination.

![a72-meditations-of-a-dreamer-2 The author on the summit of Mt. Hood. [Photo] Maurico Portillo collection](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/a72-meditations-of-a-dreamer-2.jpg)

When I was twelve, I joined a local church youth group, aptly named “The Summit.” Within a few minutes of our first winter camping trip near Snoqualmie Pass, wet, sticky globs of snow drenched all our gear. We slept in snow caves that we’d built. My good friend and middle school football teammate Sam and I stayed up late, eating a few days’ worth of food as we shivered in our damp clothes and talked about our dreams of playing college football. The next morning, our youth leaders weren’t stoked about how much food we’d consumed in one night and how soaked we’d gotten the day before, so they made the call to retreat without attempting the summit of Guye Peak.

That was my last trip with the group. Football occupied much of my free time during the next few years, but my curiosity for the mountains remained, and I continued to hike on my own. Meanwhile, I was elected captain of our high school football team, and my name began to appear in the local newspaper after successful Friday night games. In 2012 the Obama administration implemented the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy, which allowed “Dreamers,” such as myself, who entered the US when we were younger than sixteen, limited access to higher education, work visas, and a temporary stay from being deported to countries we hardly remember. As a DACA recipient, I became eligible for athletic and academic scholarships. I ended up receiving one to play football at a private university in Chicago.

During school vacations, I returned to the Pacific Northwest, and I continued to hike with my friends up non-technical volcanoes in Washington and in Oregon. Beyond that one experience on Snoqualmie Pass, however, I never had any form of official training. When we attempted Mt. Hood, the highest peak in Oregon, I was still recovering from reconstructive ankle surgery after a season-ending football injury, and I couldn’t keep up. Mid-climb, my friends left me to enjoy the sunrise by myself. I’d recently gotten a camera and I played around with it as the sky changed hues from navy to cobalt to yellow and pale blue. I told myself I’d be back one day to get pictures from the summit.

![a72-meditations-of-a-dreamer-3 Ascending Mt. Rainier (Tahoma). [Photo] Maurico Portillo collection](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/a72-meditations-of-a-dreamer-3.jpg)

After graduating from college, I went straight into the role of a high school Spanish teacher. No longer a football player, I needed a new outlet for my athleticism and a way to set goals for myself. A good friend of mine introduced me to rock climbing. On my first trip to Smith Rock in 2017, I met an experienced climber who recommended that I pick up a copy of the mountaineering bible, Freedom of the Hills. With that and a copy of John Long’s How to Rock Climb!, I set up prusik stations in my backyard and learned rescue pulley systems and various rappelling techniques, ranging from a method of using just the rope and your body to other means that rely on devices such as an ATC and a Grigri.

As I kept reading, I realized how little I’d known during my past adventures. I remembered the thrill of reaching Camp Muir in swim trunks, running shoes, a hoodie and an ice axe for the first time when I was in high school. I didn’t have all the proper gear and I wasn’t prepared for any sort of emergency; I was just happy to be there. Since that day, the images of all those climbers preparing for their summit bids lingered in my mind. These people seemed to have no other care in the world except for their current task on hand. I envied that sense of peace, and I yearned to be in their position.

![a72-meditations-of-a-dreamer-4 On Mt. Rainier (Tahoma). [Photo] Maurico Portillo collection](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/a72-meditations-of-a-dreamer-4.jpg)

Now, I started to think about the expanding possibilities of a future in the mountains with adequate practice and training. As I applied the drive I once had for football into mountaineering, I enjoyed my hard workout sessions. I even appreciated the awkward drowsiness that I felt at high altitudes, because it reminded me that I was pushing my body to its limits. In Freedom of the Hills, the editors declared: “For the modern alpine traveler, navigation is the key to wandering at will through valleys and meadows, up cliffs and over glaciers, thereby earning the rights of a citizen in a magical land–a mountaineer with the freedom of the hills.” I longed to become a mountaineer with the freedom of the hills that would give me the rights of citizenship in a magical land. That promise was enough of a drive for me to continue. I was going to be part of something great.

One weekend, I returned to Mt. Hood alone. I started climbing at 2 a.m. on a Sunday, and as I worked my way up the rime-covered volcano, I understood why the route was called the Pearly Gates: the steps of ice and snow gleamed opalescent in the dawn light like a portal into the heavens. On the summit, I got out my camera and snapped photos in the crystalline early morning air. I could easily see Mt. St. Helens, Mt. Adams, Mt. Baker and Mt. Rainier, their pale snows gleaming in another state, hundreds of miles away. Up here, though, I wasn’t able to see any borders. In that moment, the mountains began to feel like home–the only true home which to this point has accepted me with arms wide open.

During my ascents, however, I’d often glance around and not find any people who resemble me. Nearly all my climbing partners were white. When I was on my own, other mountaineers looked right past me. Sometimes, they questioned whether I knew what I was doing, or whether I was with a guide. Their words carried a hidden message: that people like me don’t do this. My people aren’t viewed as mountaineers, let alone as alpinists. Politicians describe us as “alien,” “illegal,” “rapists,” “criminals.” We’re told, “Go back to your shit-hole country.” In 2017 President Trump tried to end the DACA program so that Dreamers could be deported, but a 2020 Supreme Court decision blocked this attempt–for now. There are approximately 800,000 Dreamers in the US today, and our future often feels more uncertain than an alpine climb.

Where is home for us, if not here? Where else can we escape to? On the US border, kids were separated from their families and put into cages. Many people with a similar legal status to mine are fighting just to stay alive in societies that don’t want us. People like me don’t typically have the privilege to live in the counter-cultural world that many climbers have become used to being able to choose freely. When I compare these struggles to my adventures in the mountains, guilt and embarrassment weigh down on me. In my case, climbing was and is a journey home. A home without borders and a home that acknowledges my presence.

THEN IN June 2019, my brother Ricky asked me if I could take him up Mt. Rainier. By then, I’d climbed the peak myself, and I felt confident in the knowledge I now had. He was a junior in high school, and he’d just placed second in a sprint relay at the state track meet. His self-assurance had grown with that experience, and though he hadn’t done any mountaineering before, I agreed. During the week leading up to our climb, I had him practice zigzagging up a hill in our parents’ yard, tied into a rope and carrying an ice axe in one hand. I also rigged a rope to a tree house and watched him prusik up and down.

![a72-meditations-of-a-dreamer-5 The author's brother Ricky Portillo studies Freedom of the Hills. [Photo] Maurico Portillo collection](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/a72-meditations-of-a-dreamer-5.jpg)

Back at Muir Camp, the alarm sounded at midnight. The stars shone like shards of ice in the dark sky. After a restless night, I unzipped my bivy sack and braced for an even deeper cold. My brother and I roped up to begin our ascent ahead of the guided groups. We hoped to dodge the conga-line up Disappointment Cleaver, a route known for loose rocks. It’s hard to grasp the true scale of a crevasse by headlamp. As we navigated through a maze of chasms, their shadows seemed almost cozy, as if they were inviting us to jump into the void. I knew how deep they were, but did Ricky? If he did, the confidence he displayed was remarkable.

Sunrise set the snow alight at the top of the Cleaver, and we took a short break in its rosy golden glow. I’d pushed Ricky really hard to this point. Although his face was hidden by his glasses, balaclava, helmet and long dark hair, I could sense his exhaustion through the quick rhythm of his breaths. When I asked him how he was feeling, he flipped me the bird. In the warm rays of the sun, our spot seemed like an inviting place to nap, and Ricky was sinking into a trance. The winds were slowly starting to pick up, and I knew we had to keep moving. After I handed him some sour gummy candy, I told him we were almost there.

Higher up, Ricky regained his energy, as if he were drawing it from the mountain itself. He asked me if he could lead, and he set off across a series of ladders over deep crevasses. We could now easily make out their depths: the pale blue hues near the surface blurred into darker layers of indigo and then faded into black. Ricky still seemed unfazed, setting his feet one by one on the rungs with decisive care.

A flock of butterflies fluttered right over us. They, too, were enjoying a clear day below the top of the volcano after their journey to their seasonal home. As the artist Favianna Rodriguez says, immigration activists have long viewed butterflies as a “symbol of fluid and peaceful migration.” These beautiful creatures represent the original rights of all living beings to roam without restrictions across the Earth. An overwhelming sense of pride and joy filled me, greater than any I’d felt on a summit before.

![a72-meditations-of-a-dreamer-6 Ricky Portillo atop Mt. Rainier (Tahoma). [Photo] Maurico Portillo collection](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/a72-meditations-of-a-dreamer-6.jpg)

![a72-meditations-of-a-dreamer-7 Maurico, happy to be sharing the mountain with his brother. [Photo] Maurico Portillo collection](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/a72-meditations-of-a-dreamer-7.jpg)

We went to take our pictures on the true apex of the mountain. As we shared days’ old lettuce, mayonnaise and chicken sandwiches that had been squished in our packs, Ricky told me to reconsider the menu for our next trip. I smiled, realizing that his complaint meant he was planning to climb with me again. We finished the rest of the sour gummy candy while the guided groups began to walk by. Ricky and I talked about how we might be the first El Salvadoran brothers to climb this mountain together. He seemed perfectly at ease on the summit; perched on the snows, he appeared as vulnerable yet as powerful as the butterflies.

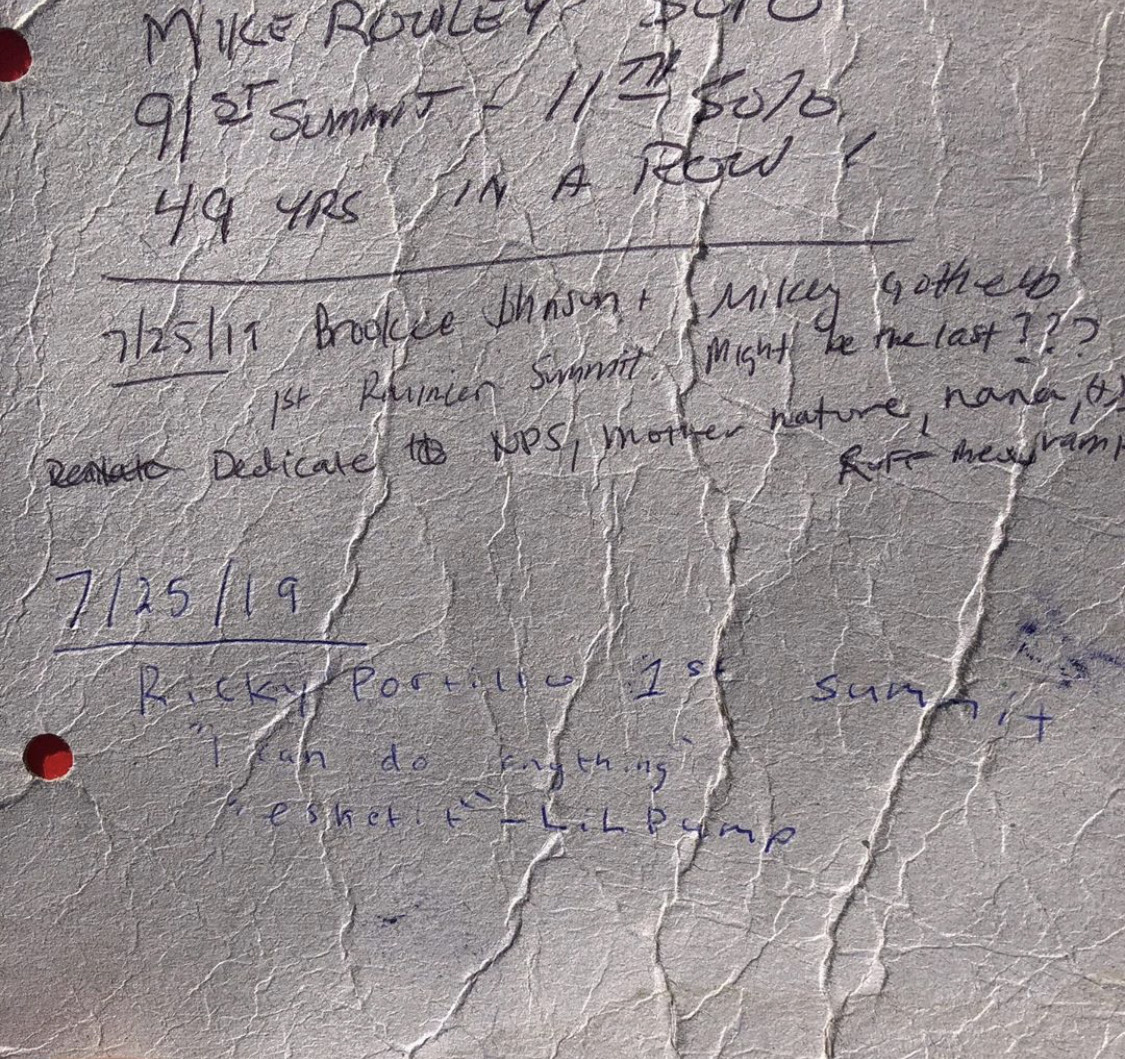

That is what representation in the outdoors can do. It can put people who are able and willing on mountaintops. People who otherwise might not be able to envision themselves there. Ricky didn’t have to question whether or not he belonged here: he could see someone who looked like him, his own brother, standing nearby. I have a feeling Ricky’s progression as a climber might be easier than mine, and that’s OK. As a citizen of these magical lands, I hope to help more people like me have better access to the rare, wild places and to the freedom I feel here. Ricky walked over to the summit registry, and he signed it with a flourish:

“Ricky Portillo, 1st summit.”

![a72-meditations-of-a-dreamer-9 The Pearly Gates on Mt. Hood. [Photo] Maurico Portillo collection](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/a72-meditations-of-a-dreamer-9.jpg)

–Mauricio Portillo, Enumclaw, Washington

[This story was originally published in the Climbing Life section of Alpinist 72. As the issue went to press on October 29, 2020, days before the next presidential election, the future of the DACA program remained uncertain. In 2017 the Trump administration attempted to rescind the DACA program. In June 2020 the Supreme Court blocked the immediate canceling of the program, with Chief Justice John Roberts writing an opinion that the Trump administration hadn’t followed the correct procedure. Since then, the Trump administration stopped accepting new applications to the program, began requiring current DACA recipients to apply to renew their protections from deportation annually instead of every two years, and delivered ambiguous messages about the overall fate of Dreamers. (In contrast, Democratic president-elect Joe Biden promised, if elected, to “send a bill to Congress creating a clear roadmap to citizenship for Dreamers”).–Ed.]