[This story from the Eiger Profile in Alpinist 41 is republished to celebrate an upcoming showing of the award-winning film Jeff Lowe’s Metanoia at the Film House at Main Street Landing, Burlington, Vermont. Show time is 7 p.m., on February 11, 2016. To download the Eiger Mountain Profile or Alpinist 41, visit iTunes, Zinio and Nook–Ed.]

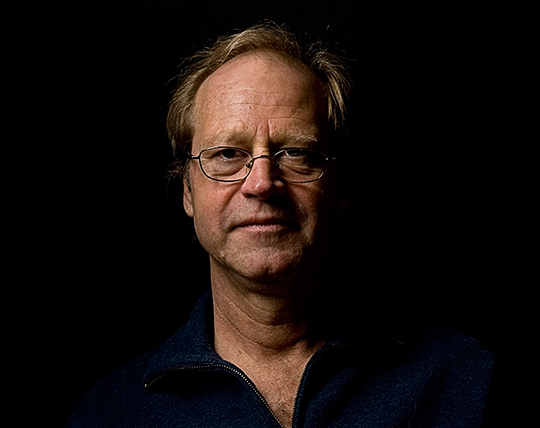

[Photo] Nathan Smith

IT’S DIFFICULT TO SEPARATE WHAT part of the Eiger’s ambience is due to its actual limestone, snow and ice, and what part is due to all the stories that played out on that grand vertical stage. I don’t think it matters at this point. Most aspirants will start with those tales finely etched in their brains. At times, along the way, they’ll climb with the souls of those who perished. That’s what happened to me.

I READ HEINRICH HARRER’S BOOK, The White Spider, when I was twelve. The epic of the first ascent never left my mind. In February 1991, I wanted to climb the North Face in a style that honored its pioneers. Anderl Heckmair and company didn’t have bolts in 1938–just simple pitons of a limited range. They risked not being able to start their crude stoves to melt water. If their cotton and wool clothing got soaked, they might freeze to death. Even to approach that commitment, I had to stack the deck against myself: go alone, in winter, without bolts, and try the hardest unclimbed route I could find on the highest part of the wall. In places where my line crossed the 1938 route or coincided with the Japanese Direttissima, I wouldn’t use in situ gear. My intention was to make the purest climb I could manage.

All extraneous concerns fell away on the face. Sometimes, when the wind was just right, I could hear snippets of conversations from the streets of Grindelwald. Proximity to civilization only served as an ironic backdrop. As I climbed behind the spot where Toni Kurz was left dangling in 1936, I could have snagged his rope with my axe and pulled him to safety. (I mimed the moves, imagining his soft words of thanks.) A blizzard pinned me for two days about a hundred and fifty yards right of the Death Bivouac. I thought of Max Sedlmayr and Karl Mehringer struggling against hypothermia in August 1935. Despite the winter cold and pounding spindrift, I was warm in my synthetic clothes and sleeping bag.

On the narrow, snow-choked catwalk of the Central Band, I was sure I could see the exact spot where John Harlin’s rope broke in 1966. Harlin was my hero when I was a young teenager. I was bothered, at the time, by his uncharacteristic expedition style on the Eiger Direct. After his fatal fall, I vowed never to jumar on a skinny rope, and I chose to climb in alpine style, which limits jumaring in the first place. At the top of the headwall, another storm trapped me in a little grotto. The chamber of my “Hermit Cave” was about six feet deep and four feet tall, with a flat floor of ice. I sat cross-legged looking into a thick curtain of spindrift. I imagined Claudio Corti’s and Stefano Longhi’s cries for help from the bottom of the Exit Cracks in 1957.

[Photo] Jon Krakauer

After days of small rations, the space between my belly and my backbone contained nothing of substance to prop me up. Shivering in waves, I stared at a picture of my two-year-old daughter, Sonja. I felt remorse for the mess I’d made of my marriage and the sense of abandonment that she would face. My awareness detached itself from my body. I could focus on any place or time and instantly be there. My soul took me to the farthest reaches of the universe and back. The clarity of sight, hearing and consciousness was like nothing I’d ever known–beyond words. When I returned to myself, still staring into the spindrift, I knew several things for certain: I knew the sound and frequency of my own vibrational DNA; I knew that Sonja would come to feel my absolute love for her and that I could still be a good father and guide her on her life-journey. And I knew that everything was OK, is always OK, in the fundamental realities of life. The spindrift thinned to a beautiful, crisp sunset. I hunkered in my sleeping bag, sending all my warm thoughts to Sonja. I fell asleep with her resting gently on my heart.

One thousand feet of unknown difficulty separated me from the summit. A big storm was due the next afternoon. March 4 dawned clear and cold. I climbed quickly toward the flint-hard ice of the Fly. Three hundred feet of diagonal crabbing shocked me into realizing how depleted I was. Doom hugged my chest. I pushed myself harder. My moves became imprecise. My left tool popped on a tiny divot. I spun into space until I could see the town of Grindelwald, two miles below. A bulge loomed directly beneath me, so I jumped away from the wall. The rope came tight against an angle piton. My shoulder and back slammed into ice. I hung, nearly unconscious, gasping for air.

Thinking of Sonja, I climbed through the pain–every move solid and fast–to a saddle near the Japanese route. Tatters of old ropes emerged on bare rock and disappeared under ice, showing the way for the last four or five pitches. It was already afternoon. Wisps of clouds swirled. David Roberts radioed to tell me about the avalanche conditions on the descent route. He suggested a helicopter pickup from the summit ridge. My initial reaction was “No way.” But my cosmic journey in the Hermit Cave, and the image of my daughter’s angelic face, outweighed any other consideration. With little time left, I hung my pack from an ice screw and ran out the rope to its end at a band of loose blocks. I found nothing solid enough for protection. I untied and scrambled the short distance to meet the helicopter on top.

I named the route “Metanoia.” For thousands of years, shamans and spiritual seekers have starved themselves, endured long days of toil, and meditated for weeks in hopes of receiving some sort of vision or nirvana. On the Eiger, I’d felt a fundamental change of thinking and a subtle transformation of heart.