[This On Belay story originally appeared in Alpinist 63, which is now available on newsstands and in our online store. A video by Dave Anderson about the trip can be found here.–Ed.]

![a63-on-belay-ride-the-wind-1 Szu-ting Yi crosses Bonney Pass, with Mt. Helen (13,620') in the background. [Photo] Dave Anderson](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/a63-on-belay-ride-the-wind-1.jpg)

SEPTEMBER 12, 2017: The wind blew under the edges of our pyramid-shaped tent, cold blasts of alpine air that seemed to stretch the thin fabric toward a breaking point. With each blow, my imagination filled with visions of the granite boulders that teetered on the slopes overhead. I sat up in the darkness and grabbed the vibrating center pole just as it bent to its limit.

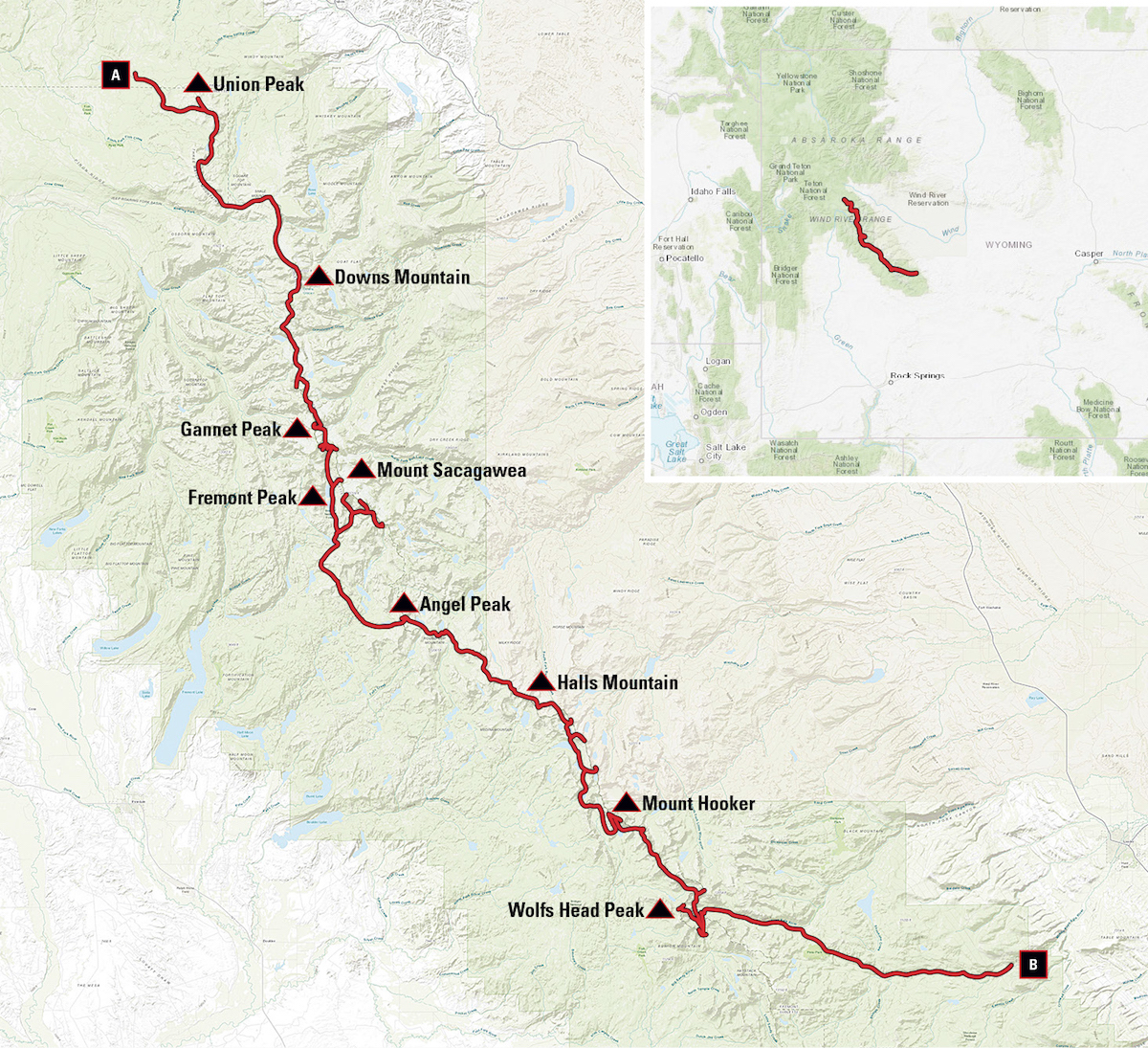

I rose early and urged my husband, Dave, to start the day. Dave groaned as he arched his back and stretched his arms; then, without prompting, he lit the stove to make coffee. The gusts kept pursuing us while we stumbled around blackroot sedge hummocks in the flats of the valley. Ahead of me, Dave’s headlamp threw jagged shadows up the talus while he weighted and unweighted the boulders underfoot, timing his steps concisely with the pulse of the wind. By the time we’d summited Tower Peak and Mt. Hooker, my hair swirled out of control. Gusts flattened the yellowing grass as we contoured the hillside toward Hailey Pass. Was this a sign of an oncoming storm? I wondered. Dave and I had no means to communicate with the outside world since we started our journey at Union Pass thirteen days ago–intent on traversing the entire 100-plus miles of the Wind River Range and climbing all forty-three peaks on the Continental Divide that are named (on 2015 USGS maps).

The midday sun dazzled off mica-rich gravel. I squinted at some moving objects beside a wooden sign. With a few more blinks, I verified them as people, and I hurried toward them. A backpacking couple from Seattle, they had been deep in the mountains for as long as we had, but they passed along a warning of “a big snowstorm in two days” from another family they’d met. I looked southeast at Dike Mountain and traced the Divide. The crest line followed gentle swells of dark-colored boulders toward an apex formed of granite wedges before it vanished into distant haze of the autumnal sky.

“Doesn’t look too bad,” Dave’s voice rose behind me. By the time he finished his sentence, he was standing next to me, giving my shoulder a gentle nudge. My sleeves ballooned and shook loudly, as if foreshadowing the coming storm. Its precipitation would split along the Divide into two opposite directions: the Atlantic and the Pacific. What will happen to us then?

Beyond the coarse-grained granite of Dike Mountain and the steep talus of Mt. Washakie, we camped by a pool of melted snow. Exhausted by then, we slept soundly through the barrage of gusts. Early the next morning, we scrambled down the northeast ridge of Bair Peak, following a faint game trail and then a well-trotted path to the north side of Barren and Texas lakes. Despite all this evidence of previous travel, we saw no animals and no other humans. Only wild flowers murmured as the wind rippled the clear, emerald water and disturbed the quicksilver reflection of Camel’s Hump.

When I looked toward two protrusions on the skyline, I found myself searching intuitively for a potential new line up cracks, grooves and slabs to the true summit, even though I knew of an established route on the other side of the pass. Such instincts were signs that I had a climber’s mind, I reckoned. I tallied other evidence: ever since I bought my first rope in 2006, I’d continually explored granite, sandstone, basalt and conglomerate. In 2012 I’d started making first ascents with Dave. In the Shaluli Shan of China, we’d escaped lightning bolts on the top of Mt. Kemailong and rappelled into unknown shadows. In the Avellano Range of Patagonia, we’d clung to moss-covered rock fissures while condors glided in the fierce west wind. Camel’s Hump would be my thirty-first summit on this trip. Yet I still hesitated to claim that I was a climber, and I wasn’t sure I had the confidence to lead an expedition on my own.

At the north side of Texas Pass, the wind lulled briefly, and the quiet amplified the feel of vastness. I breathed in, allowing the cool air to awaken my senses. The soft morning light shone on everything without discrimination, until the sky, the mountains, the lake, the flowers and the dew all seemed to express some radiant essence–a oneness that assimilated me as well. The power of this solitary place would bring me contentment if I lingered, I thought.

Instead, I quickened my pace, while Dave followed close behind me, toward one of the most popular destinations of the Winds, the Cirque of the Towers. Now that we’d summited almost three quarters of our intended forty-three peaks, my commitment to completing our goal had skyrocketed. I needed to talk with people, the more the better, to verify the possibility of that storm.

As the steel gray granite amphitheater of the Cirque of the Towers came into view, we met two men on their way out of the Winds. They didn’t have any weather information, but they shared some of their food. When we told them about our journey, one of the men immediately dubbed Dave a character of the climbing thriller Vertical Limit. Before Dave looked down at his feet, I sneaked a glance at his face and caught an awkward smile. Dave’s grease-sculpted, dirty-blond hair resembled the serrated skyline. He’d fit better in a Disney comedy, I thought. I tilted my head and wondered why I was not in the imagined cast of climbers. Oh well–it was a bad movie anyway.

Behind his dark-rimmed glasses, though, a genuine excitement appeared to sparkle in the man’s eyes. His companion gave us a broad, unassuming smile, and his long, brown beard nearly touched his fleece jacket. I tried to discard my self-consciousness. Ever since I’d come to the States, I’d struggled to establish myself in unfamiliar communities: a foreign country, academia, the climbing world. As a woman and an Asian immigrant, I felt different than most of the people I met in those realms, and I often didn’t dare assert my presence. When I told Dave about my concerns, he tried to reassure me with a long list of my achievements. I was grateful for his support, but I wondered whether he could truly understand my feelings.

Just then, another fast-approaching man with a rough grey ponytail brought news of wet snow for tomorrow and the next day. Already, the sky was darkening, blurring the boundaries between air and rock. Rain could start soon. Dave and I couldn’t afford the delay of any route-finding mistakes. A silver-grey slab draped over the southwest slope of Camel’s Hump like a heavy cloak. As Dave and I began to climb, unroped, I visualized each move at a time, leaning my palms against the smooth slabs for balance, searching for ripples where my feet might find better friction. When I glanced below, the other hikers had shrunk to the size of my fingernails. I wondered whether they were concerned about us. Even though a fall would be catastrophic, I knew we wouldn’t slip; Dave and I had both found a confident rhythm. Don’t worry, I spoke silently, I’m in my element here.

By the time Dave and I returned to the base, rain was splashing onto our packs. Our spectators were gone. The dim clouds had lowered, and the rock faces looked like tightly shut stage curtains. That night, in a campsite west of North Lake, I felt the pre-storm chill.

IN SUMMER 2007, I was a newly minted PhD in computer science from the University of Pennsylvania, when I decided to devote myself full-time to my newfound interest: climbing. Nine years prior, I’d traveled to the States from my home country of Taiwan to fulfill my parent’s expectations for a prestigious higher education. While I loved the intellectual challenges of my studies, after a friend invited me on a trip to the Gunks, I realized how little I understood my own body. I felt thrilled by each discovery: the way that my fingers and toes could pull and press on small wrinkles in weathered cliffs to keep my weight suspended in the air; how a slight hip twist and shoulder rotation could turn vertical movement into something laborsome or effortless. In the mountains, I felt, I could be a protagonist in my own adventures, rather than writing blocks of code and assembling them into programs for computers to carry out.

My advisor was in the midst of composing recommendation letters for me to send off to challenging postdoc positions and promising industrial opportunities, when I told her that I planned to “enjoy myself in the mountains” instead. She remained silent for a long while, and then she said in a gentle tone, “Szu-ting, you are not ambitious.”

The words punched me hard. She wasn’t just my academic supervisor; she was my mentor and role model. She seemed to believe in me more than I believed in myself, and she’d allowed me complete freedom to explore ideas. I couldn’t decipher resentment in her placid expression. But I felt a need to explain, to promise. If only I could present some comprehensive plan, I reasoned, she might appreciate my choice. All I had, though, was speculation. I stifled my urge to justify myself, and I hoped that it wouldn’t take too long to find a new direction through climbing.

I began working as an instructor for outdoor youth programs, and in February 2009, I met Dave through NOLS. On my way to Joshua Tree that October, I stopped by his apartment in Salt Lake City. A scroll of an ink wash painting occupied one wall along-side hand-carved wooden masks. He flipped through an American Alpine Journal to a photo of the ancient Lenggu Monastery by Tamotsu Nakamura. His finger traced the background skyline formed by jagged granite peaks, stopping far outside the border. “When I saw this picture, I knew there was something significant over here,” he said. His blue eyes seemed to flash as he met my gaze. In 2006 that photo had inspired his first ascent of Sachun. My imagination stirred at the idea of all that lay concealed on high mountainsides beyond the edges of the picture. I wondered what it felt like to leave behind the dotted lines of established routes–to find a new way up an unclimbed peak, to immerse myself in the uncertain and the unknown.

As I spent more time with Dave, I learned that browsing Google Earth was one of his major pastimes. Every so often he would show me “something interesting”: a sunlit 2,000-foot cliff tucked away in a remote, glaciated valley; a vast granite apron that rolled into a turquoise alpine lake; dozens of odd-shaped rock pillars that popped out from a deserted plain. Soon, he and I were traveling together to wild ranges in China, Mongolia and Patagonia. To me, the mountains often seemed unapproachable from afar. Their backlit outlines glowed as if immaculate, their faces hidden in the shadows. When I drew closer and stared longer, patterns began to appear. My mind would trace a long rift to a ledge, wander up a square corner, and hop onto a skyline crest until my body felt a strong urge to follow. It felt liberating to interpret a vertical landscape for myself without the influence of previous climbers’ ideas–simply by going out there and seeing what might happen. Yet when Dave and I speculated about potential climbs together, I usually defaulted to his propositions because he had more experience.

By 2015 Dave and I were married, and we pieced together a living out of guiding, writing, photography and film projects. We customized a van into a home on wheels, and we managed to save enough money for one or two international expeditions a year. Yet as my skills advanced, so did my frustration with his overprotection. Frequently, if he suspected that the next pitch provided limited opportunities for gear, he tried to take over the lead. He apologized and explained that he dared not even imagine losing me to alpinism. In his thirty-plus years of climbing, he’d experienced the deaths of several good friends in the mountains, including his main partner, Pete Absolon. I didn’t like the idea of Dave assuming most of the risks on our ascents: What if something happened to him? I kept that concern to myself, scared that saying it aloud would be bad luck.

I started pursuing AMGA Rock Guide certification, reasoning that the training and validation would enable me to shoulder more responsibility in our climbing partnership. In 2016, at my first meeting for the Advanced Rock Guide Course/Aspirant Exam in Red Rock, Nevada, I realized I was the only woman and the only person of color there. Despite my initial trepidation, I passed the test: I proved that I could evaluate the terrain, formulate a plan and successfully execute it. I felt ready to assert myself and to make my voice count.

Then in December, I had to undergo a hysterectomy to remove fibroid tumors that had become too large and debilitatingly painful. Afterward, I woke up shivering violently, wanting to ask for a blanket, but my voice hadn’t yet returned. I closed my eyes and let out an imaginary sigh. I was forty-one years old, and I’d just lost the ability to bear children. I’d never felt a strong pull to be a mother. Instead, I’d spent the past decade trying to find my sense of direction in the mountains, marriage and a climbing career. When the doctors told me that I couldn’t climb for six months, I found myself suddenly bewildered and disoriented, deprived of that heightened focus of synchronizing breaths, hands, feet and mind as I planned my next move on the rock.

DURING THE EARLY SUMMER OF 2017, Dave and I were working on a Southwest hiking guidebook when he said to me in a lowered voice, with an enigmatic expression on his face, “I have a perfect expedition idea for us after you recover.” By then, I was once more capable of twenty miles of rigorous walking in a day. I was fed up with being restricted to trails, unable to venture above the ground, while my imagination glided in all three dimensions. “What is it?” I replied with haste, wondering whether I had time for some trips to the gym to restore my upper body strength.

“It requires no further training,” he responded, with a note of triumph. “It’s the Winds Traverse.” From 1996 to 2008, Dave had lived in Wyoming, where he’d set the speed record of the Cirque Traverse and claimed the fastest known time for an ascent of Gannett Peak, the highest peak in the Winds and the state. For his next adventure, he’d come up with the idea of summiting all the named peaks in the range along the Continental Divide. He made one attempt with a friend, but after he moved away from Wyoming, he’d put the project on indefinite hold.

For the Traverse, we’d have to move rapidly while carrying heavy packs. In addition to climbing technical rock and mixed routes, we’d side-hill on slippery alpine tundra, front-point up hard snow, skate down scree slopes and balance along chossy ridges. At times, to keep going in the right direction, we might have to travel on unclimbed routes instead of established ones. We could use the forty-three peaks as a tick list to gauge our overall progress, but much of the experience–weather, terrain and route finding–remained uncertain.

“So…it’s like a first ascent?” I said. I felt drawn to the notion of plotting an efficient path that joined highpoints on detailed topographic maps. It reminded me of how people try to link together the significant events of their lives to create a clearer picture of who they are, to form some sense of a meaningful trajectory to their past and present–and to see how far they’ve come.

WHEN DAVE AND I first left Union Pass on August 30, 2017, we’d intended to finish the Traverse in fifteen days. In an effort to go as light as possible, we brought a 6.6mm 60-meter rope, aluminum ice axes and crampons, and a light rack of several nuts and tricams. Approach shoes were our only footwear. We planned one pound of food per day for each of us with just enough fuel to cook it. A few days beforehand, we cached some of the food and fuel at Indian Pass and North Lake.

Up and down we went: Union, Three Waters, Shale, Downs, Yukon, Pedestal, Flagstone and Bastion. We soon realized that we’d been too optimistic about our estimated travel time, and we started to ration our supplies. The thirty-five miles of travel and more than 20,000 feet of elevation change had already cost us three full days. During this part of the journey, we saw no other people. It was hard not to immerse ourselves, simply, in the sheer joy of solitude in wild places. We jumped over crystal streams that coursed through pristine snowfields, and we watched eleven mountain sheep dance through a rugged talus field. We kicked up V-shaped ice grooves as we raced each other for views of rock walls, pointy summits, wild flower meadows, turquoise lakes and crevassed glaciers.

On September 2, we reached the base of Mt. Koven. Its weathered faces seemed about to shed old skins of rock at any time. Here, we used the rope for the first time on the trip, and we climbed as carefully as possible over stones that shook beneath us. I screamed as a tombstone-sized block peeled off and slammed my lower leg against the wall. Dave’s face paled: we were more than twenty miles from the nearest road. I waited for the shock to fade to assess my condition. Fortunately, there were no fractures, just a badly bruised calf muscle. The pain slowed my pace, however, and before we dropped down to Gannett Glacier, we ran out of water.

We were now on the east side of the Divide. Dave said he hoped to find a quick way to intersect with the north ridge of Gannett Peak–a route that he’d accessed from the west side during a previous trip. But all the possibilities near the Divide looked too time-consuming–either sheer ice or rock. I followed him down a steep slope and through a col to the north rim of Gooseneck Glacier toward another, popular route. Above us, the shadows of the peaks extended dark and long on the ice, preventing a clear view of the bergschrund we’d have to cross. There wasn’t enough time to climb today; we needed to camp by a water source.

“If we have to go all the way down to sleep,” Dave said in a despondent voice as he pointed at the lower glacier thousands of feet away, “the expedition is over.”

“What? Why? No!” I said. It was merely the fourth day, and Gannett could take most of the following day. Our next cache at Indian Pass wouldn’t be until after another eight peaks; only one of them was lower than 13,000 feet. We were running out of food, and we didn’t have enough fuel left to melt snow. Reluctant, I plodded southeast toward Dinwoody Glacier in search of a stream. Nearby, the irregular edge of a moat laced around a short rock face below a small ledge. “This would be a great bivy,” I mumbled to myself. Dave soon spotted a dribble at the edge of the glacier. After filling our vessels, we returned to the ledge I’d seen to camp. At least we had water again. “Humans can survive without food for a long time!” I said.

![a63-on-belay-ride-the-wind-4 Yi bivies on Gooseneck Glacier. [Photo] Dave Anderson](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/a63-on-belay-ride-the-wind-4.jpg)

A smile flickered at the edges of Dave’s lips. With each step, the Traverse had accumulated more weight. There was an increasingly, mysteriously urgent quality to the journey, now, perhaps for both of us. At age fifty-three, Dave said he felt the pull of an unfinished project. But seeing him with his camera in hand, while he gazed across convoluted ridges on peaks he had never seen before, I could tell it wasn’t about just ticking off a route. It was about opening himself up to more possibilities–possibilities with the mountains and possibilities with me.

We went to bed as silver stars lit the night sky, and when they disappeared into the next dawn, Dave abruptly sat up. “Listen. People,” he said. Under the pale light, a distant rope team moved up the snow. They were heading to Gooseneck Glacier. They must know a way across the bergschrund, I thought. A few hours later, we arrived at the lower side of its chasm, which was still partially filled with snow. A small ice bridge spanned its width. On the other side, a three-person team was climbing up the edge of the glacier, clipping into fixed rappel anchors on nearby rocks to belay. Dave headed up the steep slope in aluminum crampons, carrying one of our light walking axes. He soon passed the party and turned into nothing more than a red dot.

![a63-on-belay-ride-the-wind-5 Dave Anderson ascends Gooseneck Couloir to Gannett Peak (13,804'). [Photo] Szu-ting Yi](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/a63-on-belay-ride-the-wind-5.jpg)

So far, on this Winds trip, we’d soloed most of the terrain, and I hadn’t needed to observe him so intently. Now, as I belayed him, I wasn’t anchored to anything. If he slipped and lost control, I’d need to react fast by jumping in the bergschrund to arrest his fall. I inhaled deeply, and I bent my knees to prepare. Far above, he appeared suddenly vulnerable and fragile against the vast snow and sky. My heart rate didn’t calm until the last curl of rope left the ground. Signaled by a tug, when I started simulclimbing, I sensed Dave’s complete trust in my footing. Although my leg still felt swollen and painful, the injury didn’t affect my movement. I pushed my weight into his fresh footprints. Ice crystals rustled under my feet, and the sounds of the other climbers’ voices dimmed. Our single red rope shot a vibrant line toward the sky without any bends or twists. We were in this together.

AFTER SUMMITING GANNETT PEAK, Dave and I threaded through the rock terrace from Gooseneck Pinnacle toward the clamshell-shaped Dinwoody Glacier. Our next five peaks curved around its south side–the Sphinx, Skyline, Miriam, Dinwoody, and Doublet. A finger of the glacier rose gently upward until it met the rock at the col north of the Sphinx, and from that point, there was supposed to be a quick scramble to the top. As we contoured the glacier to get a clearer view of the route, we stopped at the sight of a wide crevasse without any trace of a previous snow bridge. Dave stared at the overhanging ice above the void for about a minute, and then he pressed his face into his palms. “There’s no way we can cross this bergschrund,” he said, “not with the gear we have.”

Without another word, we dropped down a few hundred feet south to a moraine fenced by giant boulders. After much hopping around, we discovered a flat patch of sand barely wide enough for two snuggling sleeping pads. Sunlight flashed off a broken drinking glass next to a deserted, rusted tin can.

“These could be left from the first ascensionists,” Dave said. His mood seemed lighter.

“Why so?” I asked.

“Glass is heavy; this was before plastic was popular.” Dave replied.

From the map, Dave and I agreed that the fastest way to summit the four peaks after the Sphinx was to divide them into two groups. In both cases, we’d have to hike up Bonney Pass and follow the Divide–branching off to the west for Miriam and Skyline, to the east for Dinwoody and Doublet, and then backtracking to Bonney Pass to descend back to our base camp. Each excursion could take half a day. As the sun’s rays were leaving Dinwoody Cirque, Dave took one last look up at the Sphinx’s northeast ridge, and he frowned. “We will have to find a way up there,” he said. “Could be a first ascent.” The rocky, low-angle spine stretched for a long distance segmented by blocky steps. Here and there glimmered a few smooth slabs that might require a rope. “We probably will only have enough time to climb one more peak after the Sphinx tomorrow,” he said. He calculated that we’d have to spend three nights here to reach all five summits. We had little food left.

“We don’t have to climb the Sphinx tomorrow,” I said.

“Huh?” Dave said. My finger traced the contour lines on the map. “Do you think we can climb the other four in a day?” I said as I massaged my aching leg.

Dave nodded. “Yes, a long day perhaps.”

I proposed climbing Miriam, Skyline, Dinwoody and Doublet tomorrow. On the second day, we’d summit the Sphinx and then hike out of the Dinwoody Cirque all the way to Titcomb Basin, the base of our next peak, Mt. Sacagawea. On the other side of Bonney Pass, we’d reach a big stream, which would be easy to follow even without daylight. This way we’d only need to spend two nights here instead of three. Dave folded his arms across his chest, palms holding his elbows. His eyebrows knitted together while he went over my calculations. Eventually, he flattened the furrows on his forehead, and he grinned.

In the pre-dawn of the next day, the small spheres of our headlamp beams bounced off loose talus. From the top of Bonney Pass, we watched a vermilion sun burn through the hazy air of distant forest fires. Steps of shattered granite emerged in the growing light, and as I led on, I found a fluent cadence amid orange lichen, grey rock and steady breaths. From the top of Dinwoody, we soloed across loose chunks of dark igneous rocks and over a shimmer of alpine ice to the apex of Doublet and then up and down a ridge of granite cubes to Miriam. Dusk caught us as I led the way down from the summit of Skyline Peak. The temperatures dropped, and the snow in the couloir transformed to ice. My worn-out approach shoes wiggled in the bindings of my crampons, and I concentrated hard on each step. At our base camp, finally, I jotted down in my journal, Today we did four peaks. Tomorrow Sphinx.

![a63-on-belay-ride-the-wind-3 Yi on the east face of the Sphinx (13,258'). [Photo] Dave Anderson](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/a63-on-belay-ride-the-wind-3.jpg)

BY SEPTEMBER 6, we’d climbed the Sphinx, Mt. Sacagawea and Fremont Peak, and we’d arrived at our cache at Indian Pass. When we opened our bear canister, Dave indulged in a quarter of a dark chocolate bar, and he said with a chirpy tone, “The broken glass at the moraine could have been left by Miriam.”

“Miriam, the peak?” I asked. It was my turn to be puzzled.

“Yes, but I meant Miriam Underhill. She also climbed with her husband. Just like us.”

Dave told me about Miriam’s 1934 article on “manless alpine climbing” in National Geographic. Years before she and her husband ventured into the Winds and climbed her namesake peak, Miriam had already secured her place in mountaineering history with all-female ascents in the Alps. Later, when I read the words in her autobiography, her arguments for independence resonated strongly with me:

The person who invariably climbs behind a good leader, guide or amateur…enjoys only a part of all the varied delights and rewards of climbing…. The one who goes up first on the rope has even more fun, as he solves the immediate problems of technique, tactics and strategy as they occur…. I saw no reason why women, ipso facto, should be incapable of leading a good climb.

I longed for the self-assurance that I imagined she possessed–a desire that went beyond merely going first on the rope, that had to do with applying my own skills and judgment in an ever-changing mountain environment and carrying out my own vision of climbing, whatever that might be. There was an exhilaration to feeling myself grow in this range as I pieced together an improbable-looking descent, retightened a wind-shuddering tent, or threw a loop of rope over a terrain feature to give Dave a quick belay and keep us moving fast toward the next summit. What I’d originally told my advisor–that I wanted to “enjoy myself in the mountains”–could be my real ambition after all. It was just that I hadn’t until recently begun to understand what those words might really mean to me.

ON SEPTEMBER 8, after climbing Fremont, Jackson and Knife Point, we left behind the glaciers of the Northern Winds for alpine meadows that still burst with color. Purple primroses, scarlet paintbrushes and delicate yellow avens bobbed in the autumn air. Dave had never visited the next seven peaks ahead of us, and we hadn’t found much information about the technical nature of the climbs. For three days, the skies remained blue, and we moved quickly while the rope stayed in the pack. No longer so concerned about the passing time, I allowed myself to breathe in the wildness again. When we camped among the lakes in Bald Mountain Basin, cutthroat trout kissed the surface of the water as they rose to catch insects, spreading rings of ripples that widened and eventually disappeared into night. Elk trails guided us through dense thickets of snow willows in the Middle Fork Lake region. Flocks of migrating warblers and other songbirds descended; like us, they were using the Divide as a line of orientation while they headed south. Our journey no longer seemed like an arbitrary list of peaks to bag. Instead, I felt as if we were slipping into rhythms far older than those of modern climbers.

And then on September 12, the wind rose, pursuing us over Tower Peak, Mt. Hooker, Bair Peak and beyond, sweeping rain over us while we fled from Camel’s Hump to seek shelter by North Lake. At 3 a.m. September 14, the faint light of the moon illuminated our white tent. By the time we swallowed the last bite of precious breakfast food, raindrops drummed on the walls again. The noise crescendoed and then lasted for four hours. When the trembling of the tent alleviated a little, Dave set off for a bathroom break. I stood outside and stretched my limbs. Dark clouds tore through the stagnant mist. A few blue pieces of sky poked out, only to vanish instantly. Should we go? I bet Dave was asking himself the same question.

Dave returned with a fresh forecast from a hiker, a self-proclaimed weather guru, who’d analyzed and compared charts and satellite images from various sources: intermittent showers until a big system hit later that night; a short clearing on Saturday and a much-bigger snowstorm on Tuesday. If we didn’t get out by then, we could be trapped. Dave thought we should finish the peaks of the Cirque that day and pray for little snow accumulation overnight. I looked at the diffusing mist, and I told myself that I should let Dave take charge again, that he was more familiar with this part of the range than I was and that he could find the routes more quickly.

![a63-on-belay-ride-the-wind-2 A view of the Cirque of the Towers from the top of Camel's Hump (12,537'). [Photo] Dave Anderson](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/a63-on-belay-ride-the-wind-2.jpg)

The Cirque of the Towers had transformed into a fenland. Drops of rain fell from the edges of rocks, merged into currents on slabs and became waterfalls, rejuvenating the earth. The sun was still hidden behind heavy clouds. We paused a few feet below the col between Wolfs Head and Overhanging Tower, and we donned all our layers before we stepped onto the dingy northeast side. Because of the lichen on damp rocks, we roped up right away. Though we could see the summit, Dave became disoriented by rappel anchors and cairns, which seemed to be everywhere. After reaching multiple dead ends, he announced that we should have stayed more parallel to the ridgeline. “Sorry, we could have done it with half the amount of time,” he said; his voice hinted at frustration.

I quieted my unease about the weather, and I replied with a gentle smile, “It’s OK.” I realized I was also comforting myself. From the top of Overhanging Tower, Dave looked behind, and he sighed. Dark clouds whirled all around. Soon they would envelop us. Tears accumulated in my eyes at the thought that our trip had come to an end. A thunderclap hurried me into action. As we rappelled to the col, a lightning bolt flashed against rinsed granite walls. Rain chased us back inside the tent. It fell continuously on the fabric like fingers tapping impatiently on a table. Around noon the next day, sleet and hail began a loud hammering noise. Three hours later, it stopped. At first, amid the silence, I thought that the Cirque had recovered its serenity. Only a moment later, I realized that heavy snow had blanketed the tent and muffled all sound.

THOUGH THE AIR WENT STILL during the night of September 15, my alarm seemed to reawaken the storm. At 6 a.m. I unzipped the tent door for a few inches: hefty snowflakes swirled against the mountain cliffs, tree branches and tent fabric before slowly settling on the ground. At noon the sun flared through the dull sky, and red squirrels chattered as they searched for scraps of food. They seemed anxious about the unexpected early winter. The shrill calls of a robin echoed.

“The bird is chirping, which means the weather is going to clear,” Dave said.

I snorted. “It was just an overly positive robin.”

Snow began to dump again, filling the gaps between the boulders, heaping up in piles on mounds of grass. At last, I let out a sob. I kept crying until I drained all the months of pent-up agitation since my surgery, and I fell asleep.

Dave shook me awake at 3 p.m., told me that the snow had stopped, and invited me to climb Mitchell Peak. But while we were replenishing ourselves with some trail mix, the snow started to fall heavily again. This time, I was speechless. We peeked out of the tent for a final condition check before dusk. Grey hues covered the entire sky, stripping the snow of any splendor. Everything looked pale and lifeless.

“What if tomorrow is good?” I said.

“We should hike out,” Dave said. “The snow is not going to melt and both the routes up to Shark’s Nose and Block Tower won’t get morning sun or any sun at all.”

“We can climb the Cirque clockwise; the snow will have time to melt if the temperature is warm enough,” I said. “If the climbing gets hideous, we bail and call it.”

“There is not enough time to climb all forty-three peaks. After all, this is just our made-up goal,” Dave said. “Getting stuck here is not wise.”

“Yvon Chouinard once said that if you want to win, play your own game,” I replied. “We like to play our own games, but games have rules. Once we are in, we should do our best. Not forty-three, but as many as possible. I can sacrifice sleep and hike nonstop to at least below the snowline before Tuesday.”

For a long time, Dave’s attention seemed to drift away. The shadows in the tent accentuated the lines in his emaciated cheeks. He finally regained eye contact with me. “Do you think I’m not trying hard enough?” he said with a weak and tired voice. His eyes were bloodshot, and his lips trembled slightly.

His reaction stunned me. I was the one who hadn’t been trying hard enough, I thought. “No,” I said. “You have always been my safety backup. In the past, when you said it was time to retreat, I always did without raising questions. As a result, you also kept ‘unnecessary’ hardship at arm’s length from me. Remember how you practiced an exposed bivy when you were a teenager? How it was so terrible that you swore to do everything possible to keep from doing it again? I need that. I don’t want to die either, but I need to fail.” I grabbed Dave’s hands, and I spoke softly, “Thank you for looking out for me. Please help me to own my own decisions.”

In silence, Dave squeezed my hands tightly. The plan was set. On the morning of September 17, the sky turned a transparent blue. With each step I took, the snow rose higher than mid-calf, and before I could commit my weight, I had to discern what was underneath my soles–soil, grass, lichen, bare boulder or ice? Each time I steadied myself on a rime-coated slab, I turned to check Dave’s whereabouts. His mild, slouching figure was never far behind. As if he could detect my concern, he raised his head to gain eye contact with me.

My soaked feet were losing sensation, and I couldn’t rewarm them by standing on the exposed tips of boulders. The climb felt even worse than I expected, but I was out here exposed to it with all my senses–not back in the tent, theorizing about some abstract likelihood of success. Aware of the risks of falling, I focused until I felt a heightened consciousness of the nuances of the crumbling snow beneath my feet–the way it peeled outward to reveal a mound of firm soil or fell inward to signal a cavity. The occasional crisp sound of our voices asking about each other’s well-being faded into a powerful silence. It was as if an invisible rope connected us, and our thoughts and movements merged into one. The first line of giant boulders appeared on the ridge above, engulfed by soft, fresh snow. Dave paused to shatter a thin layer of ice over the stone. I knew the difficulty and danger of travel would only increase, and as the angle of the slabs steepened, I said to him, “Let’s head back down.” He nodded. Though we were still ten peaks shy of our goal, I turned around without regret.

I’d been searching for a milestone to mark my progress in climbing. In the Winds, I’d found something other than a set of numbers: the pleasant crunch of crampons as I skipped past delicate ice sheets, the sensation of riding the gusts of the winds and the momentum of my own legs as I ran down rolling talus and jumped onto flowery meadows. My imagination had translated the contour lines on the map into potential routes on rock and snow, and my hands and feet had fine-tuned the final trajectory between lakes and ridges, summits and slabs. Instead of a single direction, I’d discovered multiple paths that rose up and down many varied kinds of terrain that branched outward, intertwined and looped back, and yet kept going forward. When I voiced my decision to retreat on the last summit, I’d relaxed, as if every part of me were connecting and falling into alignment, becoming whole. More than forty-three summits, this is what had mattered: to make my own choices and to feel comfortable about myself.

![a63-on-belay-ride-the-wind-7 Anderson down climbs Dinwoody Peak (13,480'). [Photo] Szu-ting Yi](https://dev.alpinist.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/a63-on-belay-ride-the-wind-7.jpg)

We surfed on hurricane-force gusts over Jackass Pass, whirls of dry pine needles dancing around us. Before we turned away from the white-capped waves of Lonesome Lake and entered the sheltered forests along the north fork of the Popo Agie River, I glanced back at the Cirque of the Towers for the last time. Flurries filled the air once more. The afternoon sun electrified the crystals of snow into a sparkling, wind-tossed sea of light, covering the sinuous paths and knotted rappel anchors. I watched as all signs of other climbers’ forays disappeared, briefly, into the whiteout. I no longer felt a hint of loss or concern: I didn’t need any guideposts anymore. I would derive my own order from perceived chaos. I would transform foreignness into closeness. I would open myself to the wilds and respond with grace, determination, strength and caring. And I would find a way to bring back what I’d gathered up–of rain and wind, ice and rime, starlight and storm–into a truly equal partnership with the man I love.

Above us, the westerly gale ripped over the summit of Mitchell Peak, depositing the snow on its lee side. A bright line clearly marked the Continental Divide. I smiled and whispered to the mountains, “I know, just not today.”

–Szu-ting Yi

[A video by Dave Anderson about the trip can be found here. This On Belay story originally appeared in Alpinist 63, which is now available on newsstands and in our online store.–Ed.]