[Photo] Courtesy American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming

Last summer, while interning at Alpinist, I set out to learn about the life of mountaineer and mathematician Don Jensen, to supplement Doug Robinson’s Mountain Profile of the Palisades (Alpinist 48) and to explain the provenance of his famous pack. Prying into lives isn’t out of the ordinary for profile-writing journalists–I’ve written a few–but never before had I attempted to know someone whose last words had been uttered so long ago. Finding Jensen was to become a journey that bordered on nothing less than obsession, and at summer’s end, I learned far more than the simple details that I sought.

The search was complicated because Don Jensen wasn’t there to speak for himself; he mainly existed in the memories of others, a smoky figure whose story ignites, flickers, and then disappears. He died at thirty, and based on a paucity of published works – he seemed content to let others do the documenting of his expeditions – he left us with few clues about his inner life.

Where to begin? There were, of course, the memoirs of David Roberts, who met Jensen at the Harvard Mountaineering Club and famously wrote about him in his accounts of the Huntington (The Mountain of My Fear) and Deborah (Deborah: A Wilderness Narrative) expeditions, and in his memoir, On the Ridge Between Life and Death. Roberts called Jensen the climbing partner with whom he “had wound my half of our double helix of destiny, had plotted a limitless future of unclimbed mountains all over the globe,” and he chronicled their adventures in intense psychological detail, sketching Jensen as a brilliant and inventive but lonesome figure who chafed at Harvard’s insular culture and city life. When Cambridge became too claustrophobic, Jensen decamped for his home range, the Sierra Nevada, and “his beloved Palisades.” And then in 1964, Jensen left Harvard for good. He returned to California, enrolled at Fresno State College, and guided summers in the Palisades for Larry Williams’ Mountaineering Guide Service and later for the Palisade School of Mountaineering. I emailed Roberts several times, but never heard from him.

I knew from Doug Robinson’s stories that Jensen had wandered the Sierra alone in the early Sixties, spent a winter below Middle Palisade, guided at the Palisade School of Mountaineering and roamed between the glacier and the backside of the Sierra Crest as casually as a Greenwich Village habitue of the era might have strolled between the Cafe Wha and Washington Square Park. Given his climbing vita and knowledge of the place, he was undoubtedly the strongest alpinist working at PSOM, or perhaps in the entire Sierra. He had married Joan Vyverberg in July of 1968. The ceremony was held near Glacier Lodge, and they held a feast for a few friends on the so-called Banquet Boulder, an enormous flat-topped erratic up the North Fork of Big Pine Creek.

In the late autumn of the previous year, I had hiked up the North Fork with Robinson, who knew Jensen from PSOM days. Robinson veered off the trail to visit the Banquet Boulder on the way up to Second Lake. He recounted how fortunate he had been to have Jensen as a mentor. “He was, without a doubt, the most advanced Alaska mountaineer at the time – and unbelievably, he was here!” (Read more about Robinson’s relationship with Jensen and his years in the Palisades in the Alpinist 48 Mountain Profile)

I asked Robinson what had become of Joan, and he shrugged, said something about “maybe Canada,” and that was it.

And now, six months later, I was determined to find her, because she was obviously the missing link. If I could contact her in time, maybe she’d even consider writing an essay for the upcoming issue of the magazine. I scoured online databases for two days, and finally found a Joan nee Vyverberg in Florida. I was able to track down her phone number, left several messages, but received no reply. I found her daughter on Facebook, IM’d her with the reason for my interest, and received a terse reply that made clear that this was not Don’s Joan: “My mother has never climbed anything in her life.”

[Photo] Larry Horton collection

I next launched a search for Larry Horton, who had formed a company in the late 60s, Rivendell Mountain Works, to bring Jensen’s backpack and tent designs to market; I figured he would have worked closely with Jensen at some point in the start-up process, and he might be able to shed some light on Jensen’s personality. Horton is now a Doctor of Oriental Medicine, and his practice is in Albuquerque, so I found his website, filled out a contact form with a request to chat, and heard from him later in the day. When we connected he told me that he hadn’t talked about Rivendell Mountain Works in years. To Horton, the Jensen Pack represented not just a product he once made and sold, but an entire way of life, and I sensed that revisiting these memories both pleased and pained him. He recounted the joy of building a small and socially responsible gear manufactory in Victor, Idaho, and the sorrow of losing it to his creditors. When I asked him about Jensen, he remembered the man’s genius, but otherwise had surprisingly little else to say. As for Joan: they hadn’t corresponded in decades. Later that day, Horton emailed me scans of Don’s hand-drawn pack patterns, along with a link to several Rivendell brochures and an ancient Rolodex card with Joan Jensen’s address and phone number. I recognized the Walnut Creek address as the Jensen family home. Both of Jensen’s parents were long dead, but I dialed the number anyway, with predictable results.

I called Don Wittenberger, the founder of YakWorks and the YakPack, who had purchased Rivendell’s assets in 1981; his sole licensee, Eric Hardee, still sews Jensen Packs on a bespoke basis. Wittenberger told me that he was inspired to acquire the company out of respect for Jensen’s genius. “I thought his designs should live on,” he said. He had no information about Joan’s whereabouts, but he was keenly interested in finding her. Later, Wittenberger emailed me a letter from Joan to Larry Horton written in the mid-Seventies; the return address it bore was from a horse ranch in the Yukon. Harried searches in that region turned up nothing, but at least I knew that Joan had once migrated north.

Meanwhile, I had become so fixated on finding Joan I had forgotten about Lin Jensen, Don’s brother, whom Roberts mentions in On the Ridge Between Life and Death. Horton, however, had remembered Lin, found him using search, corresponded with him, and forwarded me his email address. I wrote Lin, Lin wrote Joan, Joan emailed me, and we scheduled a call for the following day. And just like that, thanks to Larry Horton, I’d be speaking with Don Jensen’s wife.

As I dialed Joan’s number on a humid Vermont evening, I tried to imagine how she might be feeling waiting for my call. Anxious? I knew I certainly was. But all I had to do was ask questions; she would have to inhabit that long-ago sliver of time to answer them. Later I would find out that Joan’s memory of the Sierra surfaced while on a walk two weeks before our call; the redolence of the air reminded her of early mornings in the Palisades which was strange, because she rarely thought about her years in the Sierra. In fact, she had never talked about her former life with the friends in the small town in which she had resided for thirty-five years. As with Horton, I would both facilitate the conversation and hold the psychic space, and despite my desire to have all of my questions answered that evening, I didn’t want to overstay my welcome. We spoke for nearly three hours. Joan had been in the midst of a graduate program the University of Washington when she moved to Fresno to conduct meteorological research. One evening she wandered into a small Sierra Club slideshow given by a Fresno State College student by the name of Don Jensen who had climbed a bit in the Alaska Range. They took up together immediately, which Joan writes about here.

Their seven years together were wonderful and far too few. They married in 1968. She moved to Los Angeles to join Jensen in a small, plain apartment located next to the University of Southern California, where he was completing a Ph.D. in mathematical logic. They spent summers in the Palisades; Jensen guided while Joan worked as PSOM’s camp cook. Joan became a proficient climber, and they put up a new route on Temple Crag (Surgicle, II, 5.7), early repeats on the Celestial Aretes, and the first traverse of the fifth-class Palisade Crest. Jensen eventually earned his doctorate and searched for work in Canada to escape being drafted into the Vietnam War. They traveled to Chamonix and the Yukon’s Ross River, where they built a shack and staked a claim on the land; they planned to return and build a cabin. Jensen eventually found a post at the University of Waterloo in Ontario. They spent two years there before he received a one-year post-doc fellowship at Scotland’s University of Aberdeen, where they moved in 1973. Jensen was killed that autumn, struck by a lorry while riding a bike to school on any icy November morning. After his death, Joan stayed on at the school; she had nowhere else to go. The renowned World War II code breaker, R.V. Jones, the chair of the Natural Philosophy Department where Joan worked, extended Jensen’s fellowship to her. She remained for six months, and then returned to Waterloo in the summer of ’74, packed up their house and put most of the belongings in storage. She returned to the Yukon, where she worked at a mill pulling and grading lumber. Eventually, she moved to a small community in northern British Columbia that she’s never left. Although she returned briefly to California in the mid-80s for a master’s degree in psychology.

“We were soul mates,” said Joan. “We loved doing the same things. We were enmeshed.”

I asked about the moodiness Roberts had written about in Deborah.

“I never saw any of that,” she said. “He was really fun to live with, enthusiastic about what he was doing, whether it was math, or climbing or cooking. His enthusiasm would transfer to people. And he was thoughtful. He had ideas about different, interesting things to do. He supported me, encouraged me. That’s what made him such a great guide,” she said. “His clients always loved him. He was gentle and encouraging. He’d make suggestions, but in a kind way.”

I asked her how he carried himself, how he came across. Joan described him as about 5’8,” lean, well muscled. He spoke in a confident but quiet baritone. She described the injury to his lip, which he had sustained in a crevasse fall when he and Roberts were retreating from Deborah: it looked like a cleft palate surgery scar. Later in life, Jensen wore a beard. He was self-assured, but he hadn’t always been so; he was overweight in high school, and the family doctor told him to lose weight, which he did by climbing Mt. Diablo daily.

It was time to bring the conversation to an end. Of course, she’d be happy to write an essay about her years with Don in the Palisades Yes, some of Don’s possessions were stowed in her attic: gear, inventions, and photographs, an ice axe, and more (unfortunately, no Jensen Pack). She remembered shipping several boxes of Don’s letters to the University of Wyoming after being contacted by Gene Gressley, the director of a new museum on campus. She assumed the documents were still in Laramie, and a quick phone call confirmed that they were.

In late August I was seated at the University of Wyoming’s American Heritage Center, awaiting the delivery of the Don C. Jensen Collection, which was packaged in four rectangular archival boxes. As I lifted the lid from the first arbitrarily chosen carton, I sensed that I was about to peer into a sarcophagus; few if any had explored these papers since they arrived in the mid-70s. The musty odor of decades-old paperwork and leather journal covers and clippings effervesced from the dim holdings, light hit the contents, et voila: neatly organized by expedition were Jensen’s voluminous notes and ephemera: Deborah (1964), Huntington (1965), and Deborah (1967). Each file contained a small journal and dozens of pages of expedition logistics, maps, photographs, letters, newspaper clippings, and scribblings about gear designs. I realized I’d need half a day to wade through this box alone. Meanwhile, in “Deborah 1964” I came across a piece of ruled notebook paper, notes for various gear he planned to make, including a new backpack. Jensen had written in pencil, and the graphite etchings were faded but distinct:

“[T]hese should be extremely light (perhaps ripstop). They should be large enough to relay loads…must be small enough to be useful…must be able to carry sleeping bag conveniently and flatly – must be able to withstand rappel. Perhaps combination day pack belt bag…” These incipient musings, of course, would form the basis of Jensen’s eponymous pack.

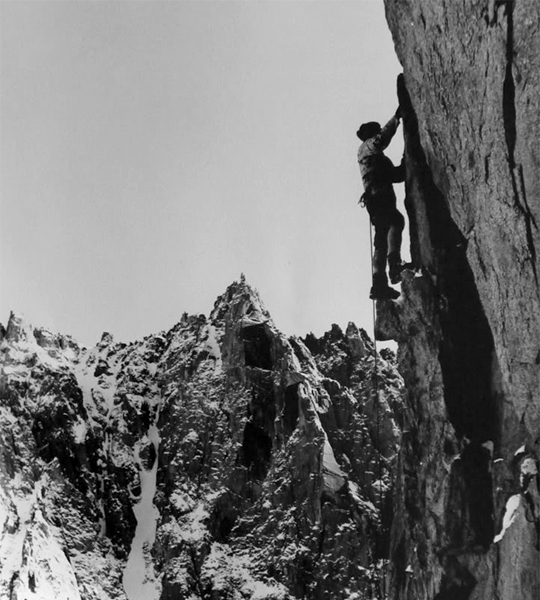

A second box contained a trove of information about the Palisades, including Jensen’s illustrations of various technical paths around and through the South and North Fork sections of the Sierra, and his original route descriptions for the Palisade Crest and the Twilight Pillar on Norman Clyde Peak. I also found maps with the locations of Jensen’s hidden caches, garbage cans stuffed with food and sleeping bags, which he intended to use for his Alpalet and Alpaline tours. Also, I found a folder containing a mass of paperwork from the Palisade School of Mountaineering, along with letters from Allen Steck, Galen Rowell, Doug Robinson, and others. Here was Don’s membership card to the East Willow Alpine Club, signed by Smoke Blanchard, and the hero shot of Jensen, climbing Rebuffat-like, later used in Alpinist 48.

I opened a third box to find a papier mache model of the Ruth Gorge and the Mooses Tooth constructed on panel of cardboard cut from a wine box. On the bottom Jensen had written, “Done to keep sane while studying for PhD exam.” The fourth box contained a mess of photos from Jensen’s Alaska expeditions – more than I had time to catalog.

I spent two days sifting through Jensen’s life. Finally, as evening fell on Laramie, thoroughly sated and somewhat sad, I closed the last of the boxes and wondered who would be the next to pore over the collection. I hoped it would be Joan, but my work here was done.

Or was it?

In his 1970 treatise on psycho-social development, Radical Man, the organizational theorist Charles Hampden-Turner posited that we humans grow by freely risking our preconceived notions of self to interact with others; whether the resulting encounters are unconscious or planned, confirming or disconfirming, we reap insights that, if we’re open to them, reform ossified habits of mind, which, in turn, lead to a more informed sense of self. Risking self to engage with others mindfully, according to Hampden-Turner, was a radical and necessary move to create synergies to un-fuck the world, which appeared to be unraveling when he wrote the book. Plus, ca change…

Indeed, the search for Jensen required “letting go” of my own ego and self-concept to enter into privileged dialogue with at least two people who freely risked emotional tumult by revisiting their mental and emotional Wayback Machines. At the risk of stepping too far into the realm of transpersonal psychology, you might say that Jensen led me to Joan and Larry, who allowed me to receive their stories, which imbued me with a sense of kinship and yes, slightly greater insight and optimism. I can only hope it did the same for them.

The search for Jensen, as all good journeys do, brought me right back to myself.

Brad Rassler’s article on the Jensen pack in Alpinist 48.

See also the story of Jensen’s pack and Bombshelter tent by Bruce Johnson on his “History of Gear” website.