[Photo] Genevieve Hudson

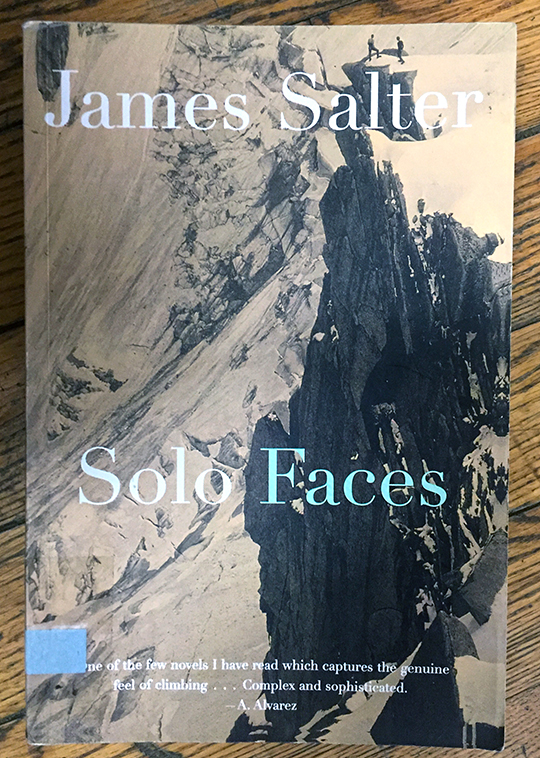

Before I left for Chamonix to go hiking in the French Alps, I borrowed Solo Faces by James Salter from the lending library at work. My list of must-reads was long and only growing longer, but the ghostly mountain landscape of its cover caught my eye–a silhouetted man ascending a jagged peak. The image seemed fitting, since I would be going to the French Alps the next day for a week of hiking. It also made me think of Matt. He wasn’t coming on this trip. We hadn’t talked in years.

I didn’t grow up near the mountains. My family wasn’t the type to ski or climb or hike. I was raised in the humid heat of rolling Alabama hills. I didn’t discover rock climbing until I went to college in the Carolinas. It was there I started to take weekend trips with Matt, my boyfriend at the time, to the Blue Ridge Mountains one state north. We’d camp among the Pisgah pines and under stormy southern skies, and then wake and make our way up multipitch routes on Laurel Knob, Looking Glass and Rumbling Bald. We’d fasten ourselves to the sides of cliffs long enough to eat lunch, our feet dangling like branches in the wind. Matt taught me how to rappel off exposed bluffs, detect fingernail-sized holds in the sides of the smoothest rock, and tie a knot that held my body weight.

One summer, he took a job at a mountaineering shop in Jackson, Wyoming. We spent three months apart, and at the end of August, I flew out to visit him. It was the first time I’d seen snow, much less glaciers. Glaciers in the summer, snow in July–my stomach clenched. The Tetons glimmered on a horizon shellacked in blue ice. We attached axes to our backpacks and started up the Middle Teton’s Southwest Couloir. We were going for the summit. Matt showed me how to self-arrest.

“It’ll keep you from sliding all the way back to Jackson,” he said with a smile.

Matt was living his alpine dream. Hours spent flipping through pages of climbing magazines in the comfort of our sea-level apartment in Charleston had materialized into a high-altitude summer in Jackson. Lean and leggy athletes slept in cars filled with nothing but well-cared-for gear. Their blue- and red-flecked climbing ropes were arranged on their back seats like altars. To me, their eyes appeared as calm and sharp as sheets of ice. They moved with seemingly measured intention through town, assembling things for their next journey into the backcountry. Stories circulated about someone who went out one morning and never came back.

The people Matt shared an apartment with reveled in the mythology and folklore of the outdoors. They spoke of slacklines suspended hundreds of feet above canyons, watched videos of themselves in kayaks, gliding down waterfalls frothed with whitewater. They never seemed afraid. I wasn’t sure if they had mastered the stillness of the mind or the art of denial or the ability to present an illusion. Perhaps all three.

After a day in the high mountains, Matt’s new friends lightly clutched the necks of their bottles around campfire embers well into the night. In another life, they might’ve been hermits cloistered in the mountains, seeking God. It was a camaraderie of divine or reckless brotherhood, and I didn’t know whether to applaud or shudder. Their ability to suspend fear almost scared me.

It wasn’t until I’d pitched my tent under the snowy gaze of Mont Blanc and began the first chapters of Solo Faces that I realized just how relevant it was to read this novel during my trip to the French alpine town of Chamonix. The events of the book unfolded, unknown to me when I snatched it from work, in the same location where I was traveling. The sun didn’t set until after ten, so light still spilled down from the sky as I lay in the grass after a long day of hiking in the Aiguilles Rouges. I rubbed the knots from my thighs and began to read about the mountains and the town around me.

Chamonix is credited as the birthplace of mountaineering. Bronze statues of famous mountaineers and their fabled ascents are scattered through the city. It’s a nod to the impact climbing has had on the region. Salter’s description is apt:

Chamonix was at one time an unspoiled town…. It lies in a deep V in the mountains, in the valley of the Arve, a river white with rock dust that rushes in a frenzy beside the streets. Overshadowing the town are the lower slopes of Mont Blanc with snouts of glaciers alongside…. It is a block of mountain, formed by a vast cleaving before even the time of the dinosaurs and drowned in seas that covered Europe after they disappeared.

Solo Faces follows the life of a renegade climber named Rand who left his life in California in pursuit of dangerous and dazzling climbs in the Alps outside of Chamonix. A bold adventurer and lone wanderer, Rand spends the novel pursuing audacious routes up the very mountains that flanked the valley I was exploring. Rand, though a fictional character, was drawn heavily from the real-life climbing legend Gary Hemming. Hemming became the stuff of myth in 1960s France after rescuing two German climbers stranded on the Dru. Though many people were involved in the rescue efforts, television reports and news headlines celebrated Hemming as the hero. His name still circulates in certain circles as a brooding, mercurial rambler. In The Beatnik of the Alps, Mirella Tenderini writes, “[Hemming’s] life was an ongoing contradiction. The desire to pass lightly through existence without leaving traces was in direct contrast with his continual need for approval and admiration.” Sometimes, after a difficult climb or a first ascent, Hemming would simply note that he had been out for “only a short stroll.”

Salter renders the world of climbing with such exactness that it makes my forearms ache. Over the years, I’ve become less of a participant and more of a spectator. But the stories, the lore-making inherent in the communities who seek great heights and lonely places, still enchant me. Though not a climber himself, Salter captures climbing’s mystique in startlingly crisp sentences, evoking the pursuit’s peculiar intersection of bravery, foolishness, and fear. Here is Rand facing a problem on the exposed cliff of a secluded mountain:

They came to a wide slab, chillingly exposed. The holds were slight, hardly more than scribbled lines. There was no place to put a piton. As he went on, Rand could feel a premonition, a kind of despair becoming greater, flooding him. It is belief as much as anything that allows one to cling to a wall.

I read about Rand’s rescue on the side of the stormy, avalanche-prone Dru, and the next morning hiked a glacier to see it in person. I gazed up at the face of the mountain, the very spot where Hemming had ascended to rescue the stuck German climbers. The rock was just as imposing as Salter describes: clouds shrouded the jagged lines of the summit, concealing the forms of other pilgrims on their vertical journey

Salter does not ignore the mortal danger inherent in mountaineering, though he does use it to imbue his story with a kind of romanticism that doesn’t always feel complete. More than one of the experienced climbers in his novel lose the use of their limbs or their life from long falls on famous mountains. Salter, however, seems to imbibe these accidents with an unsettling glimmer of fascination. There is little reflection on the thin lines climbers walk between vulnerability and intrepidness. Hemming’s own life ended tragically: he was found shot to death in the Grand Tetons from what most people agree was a self-inflicted wound. The novel only scrapes at the surface of why climbers like Hemming lived with such heavy contradictions, contradictions that sometimes led to the darkest finales.

Salter invokes the essence of climbers, their egos and their minds, in such a familiar way that I could not help conjuring the faces of people I once knew. Reading Solo Faces was not only like reading a guidebook to the place where I was, but also to a place where I had been. When Salter’s characters shed the trappings of ordinary life for some holy order in far-flung places (like other seekers have done for centuries), I see Matt’s face upturned to some peak with a tightness in his chest that would only dissolve when he finally found his way. I see his feet, stuffed inside orange climbing shoes, steadily ascending the face of a route we’d never tried on a rock that seemed to breathe, slowly, under my fingers.

Matt and I broke up soon after I graduated from college. I had just come out, and I wanted to start dating women. Our paths diverged. I watched him, through social media and occasional Skype dates, devote even more of his life to the mountains. Matt succumbed to his western, Teton-tinged wanderlust and moved back to Wyoming for a short time. As the last man I truly loved, Matt has become mythic to me; the time we spent together lives on in keepsakes I tout with me from city to different city–a bandana I bought in Asheville, an auburn bag we used to fill with soft, white climbing chalk. Reading Solo Faces, I felt like I was peering into a life Matt and I once longed for, one I never entered completely. One he did, at least for a while. Whether Matt is still climbing today, that I can’t say. He’s still climbing in my memory, and maybe that’s enough.

To me, this is the power in a well-written novel. It not only creates entirely new literary worlds full of rich and realistic and sometimes idealized characters, but it transports me back to real places in my life that I haven’t visited in a long time.

[A version of this essay first appeared in The Rumpus–Ed.]