We all know the Myth. We’ve heard it told and retold hundreds of times, in “motivational” speeches exhorting audiences to “climb your personal Everest,” in press releases announcing the latest person to summit for the latest reason, in corporate metaphors hailing the qualities required to overcome whatever obstacles stand in the way of “success” on the world’s highest peak.

As climbers and as readers of mountain literature, we’re also familiar with attempts to communicate the realities behind the Everest Myth. We’ve seen decades of accounts about the crowds of clients on the normal routes and about the extensive reliance on the ropes fixed, the camps placed, the oxygen bottles carried and the loads hauled by local workers. Some of us have argued in print and online that this form of “totally supported” ascent is not “climbing,” that genuine mountaineering involves more direct contact with the features of the mountain, and that the “spirit of alpinism” is about respect for the natural world, not its dominion. In 2008 the French alpinist Patrick Wagnon summed up this view in an impassioned editorial for Montagnes Magazine:

“I’m not seeking, here, to advocate an elitist discourse…but rather a return to humility, in which it’s up to the climber to adapt himself to choosing an objective within his abilities, and not to the mountain to be rendered more accessible.”

Over the years, like the editors of so many other publications around the world, and like numerous members of the climbing community, Alpinist contributors have periodically spoken out against the current problems with high-altitude tourism on Everest. And each season, as the death toll rises, the Myth only seems to grow more powerful. The climbing writer Peter Beal argues on his blog, “There is no question that Everest is a spectacle now, feeding on its own image, becoming a bigger version of itself.”

Then on April 18 of this year, sixteen Sherpa, Tamang, Gurung and Nepali high-altitude staff died in a single ice avalanche in Everest’s Khumbu Icefall. All references to individual summit dreams take on a hollow sound before the images of children’s faces contorted in grief; before the knowledge that their parents died trying to earn the money to support them and to send them to school.

Before yet another Everest season arrives next year, I believe the consequences of the Myth must be examined again, this time with an even stronger emphasis on the dangers for those whose labor helps sustain it. To look behind the layers of this mythology is not merely a matter of pointing out differences in mountaineering styles or of arguing about philosophies and motivations. In inspirational books and speeches, many clients have obscured the immense infrastructure of labor that makes their exploits possible. And to the degree that Sherpas and other local guides have become invisible in such stories, their concerns, their risks and the value of their lives have become invisible as well.

When Sherpas appear in Western narratives, their role is far too often described in terms redolent with imperial nostalgia. In a recent blog post (republished on Alpinist.com), Jemima Diki Sherpa evokes the “six-odd decades of mountaineering mythbuilding” that have led some Westerners to imagine themselves “as conquering heroes, assisted by a legion of Sherpa faithful ready–and cheerful–to lay down sweat and lives for arduous, but ultimately noble and glorious, personal successes.” On the One Mountain Thousand Summits Facebook page, the climbing writer Freddie Wilkinson alludes to “a fog of Orientalism” that has lingered over representations of Sherpas in the media, a gauzy set of projected fantasies about the exotic and the Other.

Meher H. Mehta, an elder member of the Himalayan Club recalled in a 2012 email to Alpinist: “The division of ‘them and us’ was very much an attitude of the colonials [during the early twentieth century]…. There was always the case of demarcation of the common and preferred. It was in that context that the Sherpa found entry into the mountaineering hierarchy.” Even today, depictions of Sherpas as almost-mythical, self-sacrificing beings present them, implicitly or explicitly, as subservient to the desires and expectations of Western visitors. The suffering, fears and hopes of individual Sherpas can be easily ignored in paeans to “the Sherpa people” that extol their “geographic destiny”–as if all Sherpas were preordained to spend their lives hauling heavy equipment for foreigners, cheerfully and faithfully, amid the ever-present dangers of avalanches, icefall and thin air. Such writing praises them, essentially, for ‘knowing their place.’

In Buried in the Sky (2012), Amanda Padoan and Peter Zuckerman described the widespread appropriation of the Sherpa culture and name: “The word [Sherpa] is often applied commercially to anything that helps people get around. Haul your terrier in the Sherpa Dog Carrier. Brace your belly with a Baby Sherpa Maternity Belt. Stow your bibs and burp cloths in the award-winning Alpha Sherpa diaper bag. ‘It’s no mystery how this pack got its name,’ reads the promotional website for the Evo-Sport Sherpa Rucksack. ‘The Sherpa is built to carry all your gear, and you won’t feel a thing.'” The blog Reclaiming Sherpa keeps a list of companies that use “Sherpa” as a brand, and that thus help conflate an ethnicity and a group of human beings with “goods and services.” Beneath the surface of some international Everest accounts, there’s a similar kind of dehumanization, an assumption that suffering can be passed on to hired “personal Sherpas,” who are somehow “built” to bear and endure.

A certain romanticism lies at the heart of many Western mountaineering traditions, one that has taken multiple and shifting forms: the image of the heroic individual who tests himself against the elements or who seeks to lose himself in union with nature; the valuing of transcendent moments that seem to exist outside of civilization and time. That same tendency, however, can spill over into less seemly habits of thought. As the anthropologist Sherry Ortner explains, the echoes of an older, essentializing language resound in some modern Everest tales, portraying Sherpas as if they were an inextricable part of a romanticized natural landscape, as “happy,” “unmodern” and “innocent.” During the early days of Himalayan mountaineering, this kind of rhetoric promoted the attractions of hiring Sherpas. But it also frequently denied them the right to make their own decisions about personal safety, depicting the Sherpas as “childlike” and insisting that Western expedition leaders ‘knew best’–even when they ordered Sherpas to carry loads in dangerous snow conditions (Life and Death on Mt. Everest, 1999).

Filled with ghostly remnants of this language, the Everest Myth veils the complexities of mountain workers’ lives, the scarcity of better employment that drives most local expedition staff to such hazardous jobs; the increased professional qualifications and experience of some modern Sherpa guides; the dreams of many to escape mountaineering into careers that offer less physical risk, more autonomy and more choices; the stories of Sherpas who have, in fact, succeeded in non-climbing careers in Nepal and in other parts of world; the varied cultures among the members of different ethnic groups who perform the same labor as Sherpa high-altitude staff and who are often referred to by the same name; the growing frustration of many expedition workers with the inequities of the current system; the political tensions within the country after years of struggles between Maoists and the government; the broader economic struggles that have pushed many Nepalis to seek other dangerous jobs abroad, including the hundreds of migrant workers who have died in the past few years on construction sites in Qatar.

In a 2013 article, “The Disposable Man,” Outside Senior Editor Grayson Schaffer wrote about Everest in much-needed, de-mythologized terms: “A Sherpa working above Base Camp on Everest is nearly 10 times more likely to die than a commercial fisherman–the profession the Center for Disease Control and Prevention rates as the most dangerous nonmilitary job in the US–and more then three and a half times as likely to perish than an infantryman during the first four years of the Iraq war. As a dice roll for someone paying to reach the summit, the dangers of climbing can perhaps be rationalized. But as a workplace safety statistic, 1.2 percent mortality is outrageous. There’s no other service industry in the world that so frequently kills and maims its workers for the benefits of paying clients.”

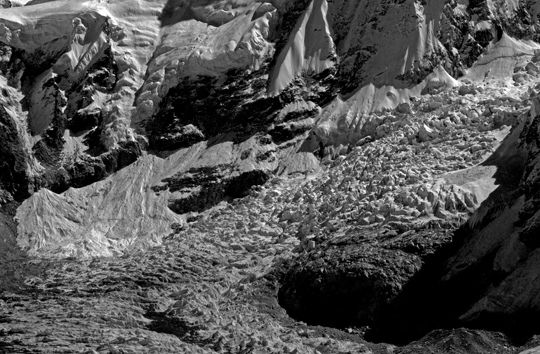

In a Guardian report this year, the British journalist Ed Douglas portrayed Everest’s labor conditions with a similar industrial language: “As factory floors go, it’s hard to imagine anywhere more dangerous. And that is what the [Khumbu] Icefall is: a place of work for the Sherpas and other high-altitude workers. It is hard to imagine anything in nature more capricious or beyond human control, yet Sherpas ferrying supplies to the upper slopes must pass through this labyrinth up to 30 times during the season. They are playing Russian roulette for a living.” To look at Everest high-altitude tourism, thus, for what it has become–a multimillion-dollar business–allows for a more serious investigation of labor relations, working conditions and inequality. It encourages a demand for better life insurance for local expedition workers. It raises questions about differences in pay between some indigenous and Western guides who have similar levels of experience.

There are other shifts in talking about Everest that may remove additional layers of the Myth. During the 1963 American Everest Expedition, the writer James Ramsey Ullman described Sherpa staff carrying loads from Advance Base Camp: “The real job, during this phase of the climb, was being done by the Sherpas up on the Lhotse Face, and there was a glumly recurrent, though scarcely realistic, vision of their going on all the way to the top of the mountain while the sahibs cooled heels and behinds in the Western Cwm. THIRTEEN SHERPAS REACH SUMMIT OF EVEREST; AMERICANS GREET THEM ON DESCENT WITH CHEERS AND HOT TEA would be a fine message to send out to Kathmandu and the world” (Americans on Everest, 1964).

Now, when similar announcements would be accurate (albeit, perhaps, without the offer of American-brewed hot tea), we rarely see such headlines amid the media sources that report on commercial ascents. What if instead of announcing that a client “climbed Everest,” those newspapers and websites, instead, named the particular groups of local guides who prepared the route to the summit and then assisted their clients to the top? What if the term “Everest climber” were given to the people who climbed the features of the mountain directly, rather than awarded to those who ascended its pre-fixed ropes? More honest accounts might result in a clearer vision of what takes place on Everest–the beginnings, perhaps, of real discussions about effective and lasting solutions.

There has been an inherent violence to the Everest Myth: violence to the natural environment in the waste that pollutes this over-crowded mountain; to individual identities in the stereotypes that persist; to truth, and most of all, to human lives. At the same time, the Myth can give the general public the false impression that the current methods of commercial expeditions are the only way, erasing the diverse history of mountaineering styles that preceded them. When last year’s Everest fight stopped Ueli Steck, Simone Moro and Jonathan Griffith’s attempt, few people seemed to remember that others had previously climbed Everest without using fixed ropes on the Lhotse Face–or that Reinhold Messner, Erhard Loretan and Jean Troillet had proven, decades ago, that ascents could be made without high-altitude support staff.

Many have argued that Everest tourism is necessary for local economies. A few guiding companies have striven admirably to give back to communities, with a variety of programs. But after the disasters of the past few seasons, it’s time to ask: If this industry must continue in the future, can it be reorganized into new forms that might result in less suffering, discord and grief? In the aftermath of this year’s Khumbu Icefall accident, Sherpas guides and other local expedition workers are already taking action. They have demanded that the Nepali government pay more support to the families of the dead, cover medical treatment for the injured and increase the amount of life and rescue insurance for future seasons. They have asked for 30 percent of peak fees to go toward establishing a “mountain relief fund.” And they have argued for the authority of local guides to cancel a climbing season, without a financial penalty–the right to make their own decisions, at last, about when the mountain’s conditions are placing them in unacceptable risk.

More and more local guides are now speaking and writing about their experiences, taking control of their own representations in the international media. New stories, told by Sherpas from a wide variety of careers and backgrounds will increasingly tear rifts in the once-dominant narrative of the Myth. In the Nepali Times, Tashi Sherpa, a gear company owner, declares: “We cannot predict nature’s tantrums and in that we have common ground, for we do not blame anybody for the shifting of the mountain or the movement of rocks; that is the risk inherent in venture. What we cannot accept is the furtive manipulation and complicit acceptance [by others] to make more for ourselves and pay less to those that risk their lives on our behalf.”

The old paradigm of foreign visitors dictating the plots of Everest climbing narratives is ending. Instead of merely purchasing a fading illusion of heroism, could more clients (as some already do) contribute more directly to the welfare of local communities? Could the choice of guided peaks be better matched to the abilities of clients, allowing a lighter style and more natural experience for the whole team–and less exposure to objective hazards for the workers? Perhaps, Freddie Wilkinson suggests, if commercial teams could shift their focus toward other, more appropriate destinations in the Himalaya, “such a change would still bring employment and opportunity to the Sherpa community; it would avoid the ludicrous notion of using helicopters to ferry people and equipment above the [Khumbu] icefall; it would potentially spread the economic prosperity that expeditions offer to more valleys and regions of Nepal while also diluting the human impact; it would create a more respectful, and ultimately sustainable model for commercial climbing in the Himalaya. The reason, of course, why nobody has seriously talked about doing this is that the Myth is too strong. People…will always be drawn to the superlative, and there are few goals more easily defined, than reaching the highest point on planet Earth.”

But it’s important to remember that the well being of local workers is not just an issue for the Everest guiding industry. Most independent alpine-style climbers rely on low-altitude porters to carry loads to base camps, employees who remain even more invisible in international narratives than Sherpa high-altitude staff (See Campbell MacDiarmid’s article in Alpinist 42). Nick Mason asked in the 2008 Alpine Journal: “Is it radical to suggest that instead of an equipment or clothing company sponsoring yet another climber they sponsor the construction of porter shelters where they are so desperately needed in Nepal?”

By helping to overturn the false romanticism associated with the Everest Myth, we might all find unexpected ways to break seemingly ironclad conventions, to promote greater levels of both creativity and responsibility for Himalayan climbing. For the Myth, of course, can also trap some “Westerners” within its stereotypes, reinforcing the outdated imperial notions of “us and them”; blurring cultural, national and personal diversity among foreign clients and guides; reiterating patterns of expected roles that they, too, may find limiting and disturbing. In its emphasis on success and personal fulfillment, the Myth can eclipse more important values associated with alpinism, such as solidarity, self-reliance, humility and respect for mountain environments. A return to the “spirit of alpinism” on Everest might encourage something far more meaningful than any summit: a “brotherhood of the rope” that acknowledges not only the connections between climbers, but also the human bonds between every person who dwells and travels beneath Chomolungma–the original name for this still sacred peak.

[With additional reporting by Gwen Cameron.–Ed.]