The old man lay in his hospital bed, his white and blue plaid blanket pushed to one side. He wore blue plaid pajamas, and his white hair was brushed forward. All the walls were white, bare except for a white outlet and a black cord. It was time, he kept saying. His voice was sandy and thick. Oxygen pushed up a tube in his nose, and as he spoke, the air escaped, adding a hiss to his words. His eyes were closed. He was giving up on life, he said, because he couldn’t climb anymore.

Surely, he doesn’t feel that way, I thought. I couldn’t tell whether Harvey T. Carter was happy to see us or not. It was a warm March day in 2012. The room felt uncomfortably humid. Machines hummed. Nurse’s voices trickled down the hall. I’d first met Harvey in 2008 after Mike Schneiter and I repeated the International Buttress, a 2,000-foot route that Harvey had established in 1975 with Michael Kennedy in Glenwood Canyon, Colorado. The limestone cut into our fingers. A sixty-foot shield shook. I broke off a 100-pound block that exploded near Mike’s feet. Now I was staring at the man who’d climbed it first.

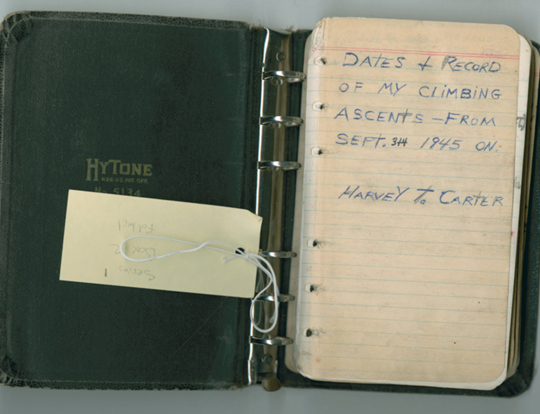

Over six decades of climbing, Harvey had completed some 5,000 first ascents. Having decided that climbers should be able to travel on any type of rock, he’d found his way up sandy, bulgy, crumbly blobs of mud and grime, with a rope tied around his waist and a rack of pins thrown over his shoulder. In December 2007, he was bouldering alone at sunset on a roadside rock when he fell and broke his leg. At twilight, a passing driver saw his body in the snow and brought him to a hospital.

Now he was eighty-one, dying of prostate cancer. I’d arrived with two of his climbing partners, Stewart Green, fifty-eight, and Jimmie Dunn, sixty-three. I was thirty-four. In them, I thought I saw a glimpse of my future: three lifetime climbers in the next stages of their lives.

Outside, hundreds of thousands of people scurried about Colorado Springs in a sprawl of stoplights, rolling hills and strip malls. Six miles to the northwest, red sandstone spires rose amid the Garden of the Gods. Because the rock was too soft for the quarter-inch bolts of the 1950s, Harvey had pounded soft-iron pins into hand-drilled holes. Later, he’d remove bolts from other people’s routes in other places, sometimes threatening violence. Thirteen miles to the west, the pink granite of Pikes Peak gleamed. Nearby, Harvey had an A-frame chalet, overlooking the pines and aspens. He’d escape there, often alone, to climb in a turbulent alpine realm. He decorated the chalet with some of the bolts he chopped. I imagined him as tough as the mountain’s hardened stone. He shook his head as if swatting a fly.

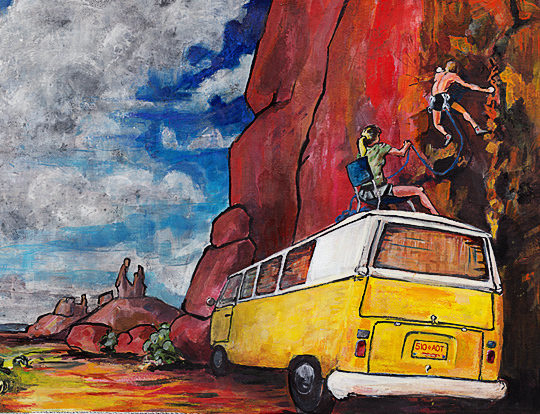

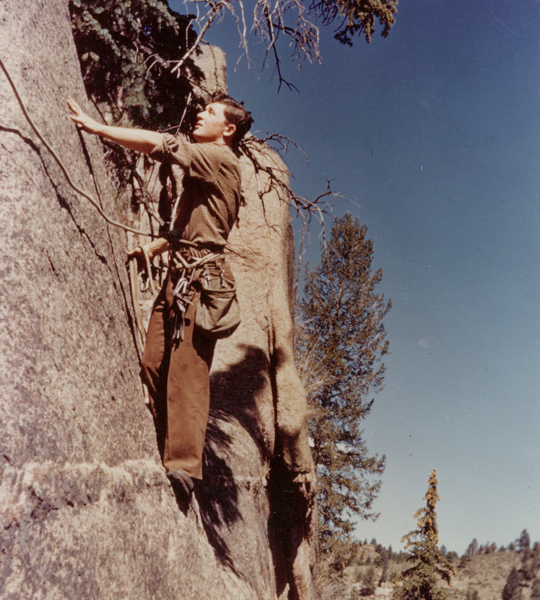

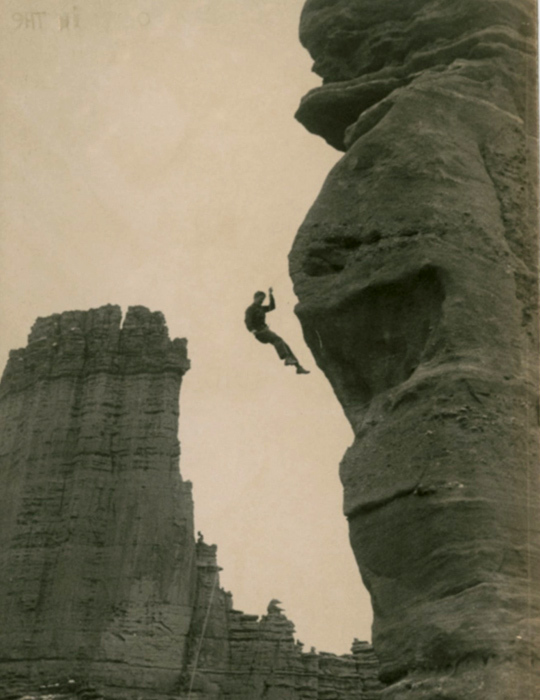

[This image came from the American Alpine Club’s Desert Pioneers online exhibit, a collection of previously unpublished artifacts of Harvey Carter, Eric Bjornstad and Huntley Ingalls, narrated by another desert-climbing legend Steve “Crusher Bartlett.”–Ed.]

Stewart, standing in the shadows, pushed up his glasses. His grey hair grew in a chaotic rim around his head. He said he wished he could take Harvey for a drive through the Garden of the Gods. Harvey opened his blue eyes. We all knew that he was too weak to go anywhere. The vibrations of the oxygen machine echoed off the walls. I asked Harvey about his first attempt on International Buttress in 1967 with Layton Kor.

“We started it,” he said, “and he was going with some girl, and he wanted to get back to her.”

The word girl sounded like a growl. “Do you wish you’d climbed more with Layton?” I asked.

“Yeah,” he said. “We should have done more.” His voice rose at the we as if he were smiling, and then it faded with a hint of loss. “We did OK.”

I told Harvey that his line up the Titan, the Sundevil Chimney, would be a challenge for any generation. Just a month before, I was climbing in Utah’s Fisher Towers. Near the top of his route, I reached deep into a flaring, bong-scarred crack–and found nowhere to place gear. I continued, one hand curled inward like a claw, fingers camming into hardened dirt, until I spied a mud-covered Star Dryvin bolt, a Harvey relic. What kind of person would climb this terrain, back when it was still unknown? I wondered. Eight hundred feet of mud-choked chimneys required goggles and a handkerchief just to see and breathe. I free climbed waterfalls of mud frozen like ice pillars. The thin ones crumbled in my hands. The thicker ones supported gingerly placed body weight.

[This image came from the American Alpine Club’s Desert Pioneers online exhibit, a collection of previously unpublished artifacts of Harvey Carter, Eric Bjornstad and Huntley Ingalls, narrated by another desert-climbing legend Steve “Crusher Bartlett.”–Ed.]

“You hear that, Harvey?” Jimmie asked, as he leaned forward. Jimmie had a way of quickening his speech, now and then, in sudden swerves like a car pulling out into traffic. He wore an old yellow synthetic jacket, zipped halfway, exposing a faded grey polo shirt. His short grey and white hair looked freshly shorn. A mustache extended below his lower lip.

Harvey closed his eyes. “It’s got a wild pitch, the crux, about halfway up,” he said. He squinted. He said he could still see the 400 feet of air on either side of his feet. What had it been like to move beyond that last piece, improvising, without knowing when the next moment of security would come? Perhaps he’d developed a kind of sonar sense, knowing just where to punch through the mud to reach a hidden solid crack.

[This image came from the American Alpine Club’s Desert Pioneers online exhibit, a collection of previously unpublished artifacts of Harvey Carter, Eric Bjornstad and Huntley Ingalls, narrated by another desert-climbing legend Steve “Crusher Bartlett.”–Ed.]

As if sensing time was running out, Jimmie rushed to another story. In October 1969, he and Harvey tried to climb the 1,100-foot South Face of Washington Column in a day. To move faster, they threw off their warm clothes and extra equipment, only to end up stranded a few hundred feet from the top. They spent the night on a cold, rock-strewn ledge, narrow as a bookshelf. Moonrise turned the Yosemite Valley floor a glowing, icy blue. Jimmie fidgeted and tried to keep warm. Harvey cradled his own head in his arms and remained motionless, completely at home.

As our visit ended, I shook Harvey’s dry, wide hand. His palms felt twice the width of mine. He stared toward the window. His head sunk into the pillow, gently, with each slow breath. Stewart, Jimmie and I were still talking about climbing, the great lines and the mud, as we exited the pale hospital doors into the blinding sun.

[This story is an excerpt from a feature in our print magazine, in which Harvey Carter’s words become a catalyst for writer Chris Van Leuven’s quest to understand how climbing prepares us for the challenges of ordinary existence, the approach of old age and the unavoidability of loss. Van Leuven then embarks on a series of conversations with three climbers, now in their fifties and sixties, whose youthful exploits resembled aspects of Carter’s career. And with Stewart Green, Ed Webster and Jimmie Dunn, he explores the consequences and rewards of choosing a focused life. Read the full story in Issue 46 of Alpinist.–Ed.]