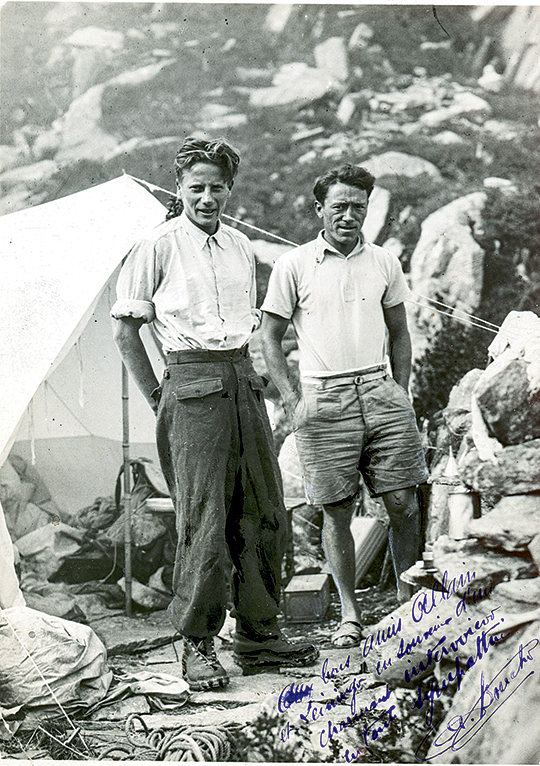

[Photo] Yves Ballu collection

DURING THE 1980S, WHEN I was the editor-in-chief of the French magazine Alpinisme et Randonnee, I spent several days in Grenoble each year for an international trade show. My meetings were exhausting work, happily interrupted by visits with good friends, which allowed me to forget, for an hour or two, everything that the show signified: that the mountains had become a business and that we–the journalists, the guides and the technical consultants–were all part of it.

The encounter that gave me the most pleasure was with a smiling, elderly gentleman who had a gentle voice and an impish gaze. Dressed like an ordinary retiree, he seemed out of place amid the flashy crowd of young athletes. It was the legendary Pierre Allain, now in his eighties, here to display the carabiners and caving ladders that he still manufactured himself, with the machine tools he’d designed.

Who would have thought, at the sight of this modest character, always joking (but without any spite) amid the climbing community he’d watched evolve for more than half a century, that this was one of the greatest alpinists of the 1930s, as well as an innovator of lightweight carabiners, rappel devices, down jackets and climbing shoes? Or that he was the first ascensionist of the North Face of the Drus!

From the valley, the austere North Face catches the eye, its surprising icy Niche glittering at two-thirds height. It was, in fact, a thunderclap when, in 1935, two Parisians, Pierre Allain and Raymond Leininger, arrived at the top. Their climbing had been shaped by the stones of Fontainebleau. Few people in those days had imagined that such miniscule rocks could provide serious training for arduous alpine climbs. The great Armand Charlet judged the boulders only good enough to “polish saucepans.” But the “Bleausards” didn’t fit in with the mountaineering establishment of the time. Parisian alpinists tended to come from the bourgeoisie. Allain was a lathe operator, and he was less inhibited by older climbing conventions.

At the time, the North Face was considered one of the “last great problems” of the Mont Blanc massif. Days before Allain and Leininger’s success, the great Swiss guide Raymond Lambert had experienced a painful defeat on the same wall. He’d made the mistake of forming a rope team of four that was too slow. Nonetheless, he’d overcome the first key section (the Lambert Crack), a dizzying passage above a narrow ledge. Beyond that point, he claimed, it wouldn’t go.

The previous year, however, some climbers had, in fact, crossed its chilly granite–albeit in reverse. A Swiss team, Robert Greloz and Andre Roch, had rappelled the wall using 260 meters of rope and a spare pair of pants. Allain hadn’t yet invented his rappel device, and climbers still abseiled by passing the rope below their butts– according to the old “Dulfersitz” method. It was a bold act: the Swiss alpinists could have become stuck mid-descent, without any possibility of a rescue. Indeed, their adventure proved eventful: a cut rope, a stuck rope, a stormy bivouac, a tempest and rockfall. Yet they concluded that an ascent was possible.

Allain, in any case, believed them. He’d meticulously organized his equipment, packing inflatable mattresses, down jackets and waterproof bivy sacks, but reducing the actual climbing gear to the minimum: sixty meters of 7mm hemp rope–“Adequate security!” he insisted in his memoir, Alpinisme et Competition–five pitons, six carabiners, no crampons, only one axe and a pair of espadrilles with crepe soles.

After a bivouac, Allain and Leininger reached Lambert’s highpoint. Allain saw a double crack above him, some forty meters high, with an overhang at the end. With his arms in both fissures, his feet in opposition on the slabs, he couldn’t place a piton for the first ten meters. Legendary alpinists who climbed the wall after him–including Lambert, who made the second ascent in 1936, with Loulou Boulaz–all confirmed that it had a difficulty without equal at the time in the entire massif.

Allain later confessed to me that he had a predilection for cracks, something of an anomaly for a Bleausard. In Fontainebleau, fissures are rare, so he’d searched them out, unearthing the “Fissure des Alpinistes” in a lost corner of the forest (now graded 5c, but Bleau grades are stiff). Unfortunately, the Fissure Allain on the Dru is no longer frequented. After the sixth ascent, in 1945, the French climber Felix Martinetti found a much easier crack to the right.

To attain the summit of the Petit Dru, Allain led an icy chimney without crampons. They weathered their second night out on the descent. All evening, the snow drifted through the darkness, yet their bivy sacks worked marvelously.

On the way up, Allain had glanced at the terrifying verticality of the West Face. “The prototype itself of the impossible,” he called it. “Here, alpinism loses its rights.” Then in 1947 Allain conceived of the P.A., a climbing shoe with a smooth, supple sole, which (renamed “EBs”) would outfit several generations of climbers around the world. Back in 1935, he couldn’t have foreseen that the West Face would eventually be crossed by several routes, and even free soloed. But without the shoes and other gear that he’d introduced–not to mention the free-climbing techniques that he’d developed in Bleau–none of those accomplishments might have been possible.

Pierre Allain didn’t retire until he was ninety. As he had never filed for patents, his designs were sometimes copied, if not pilfered, and he never made a fortune. At age eighty, still alert, he climbed the intricately winding Boell Route on the Dibona Aiguille, with his son. Despite the international success of his shoes, he never really participated in the industry of the mountains. He wasn’t a businessman: he was a free man.

Pierre Allain (1904-2000)

Raymond Leininger (1911-2003)

–Translated from the French by Katie Ives