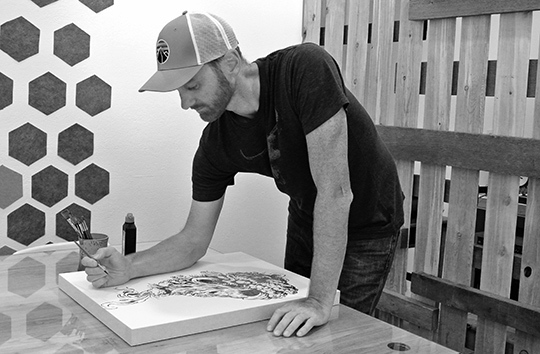

Jamie Givens, a Denver-based artist whose roots stretch back to his first studio in Brooklyn, has become a regular contributor to a host of outdoor publications by following his passion. In Alpinist, he has published black and white sketches and full-color illustrations; humorous comics and darker editorial pieces like this portrait of Reinhold Messner and his late brother Gunther is Issue 44.

His recent work includes a map of the Darran Mountains in Issue 46 as well as a portrait of Charlie Porter in Issue 47. In a blog post, Givens explored the pathways with which we reach our success, centering his journey around an illustration from Issue 45. “I was able to give Jamie a large amount of freedom for this piece,” Alpinist Art Director Mike Lorenz says. “I gave him the story, and he ran with it.” Givens’ blog on the piece is republished here.–Ed.

“To live and die any other way is shameful. Either we slip while climbing, like so many others, and the rope breaks. Or else, too old and ill to follow our team, we must spare ourselves the unbearably slow paralysis of awaiting death on some sunlit ledge. What a paradox! We know we are ultimately condemned to the fall, which is to say to a descent as infinite as it is involuntary. Perhaps it’s from an illusory attempt to avoid this fate that we believe we must climb? What are up and down, past and future, good and evil, if not the two poles that inevitably orient our lives? For us, there is no hope except in looking to the heights.”

–Sylvain Jouty; excerpted from Queen Kong (2001) and translated from the French by Edward Gauvin.

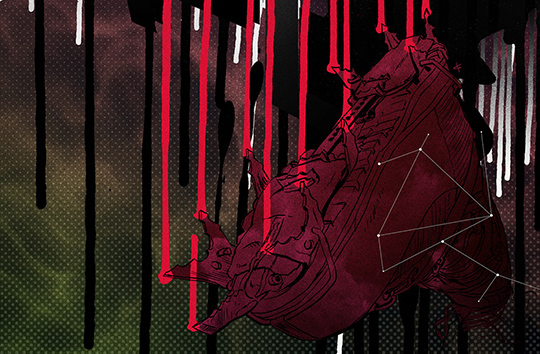

I just delivered an illustration to accompany a story by Sylvain Jouty, a French climber and mountaineer, which will appear in the Winter 2013/2014 edition of Alpinist. It was a great, esoteric, lofty and sometimes confusing piece. It even touched on themes of quantum physics, and I loved illustrating it.

It’s a pretty great thing to do work that you love. Maybe as commercial artists we don’t always have a passion for our subject matter, but to do work that we love is an awesome thing. And it doesn’t happen unless you strive for it. This got me thinking about the very beginning of my career. And that all began with the most positive and influential thing I gleaned from art school.

One day our teacher sat us down to watch a horribly grainy VHS tape of renowned illustrator Marshall Arisman giving a talk to a room of students, most likely at the School of Visual Arts in New York, where he is chair of the Illustration MFA program. While recounting his early career, Arisman described coming to the realization one day to simply “go with what you know.” He knew guns. I guess he had grown up in rural New York, and hunting and shooting were very familiar to him. He started drawing guns and related subject matter and submitted them to hunting and shooting magazines. He started to get work and got published. This was the beginning of his career.

After school, I took this to heart. Starting in college, I became obsessed with rock climbing. I devoured any climbing or mountaineering magazine. My friends and I climbed at any chance we could get. I dreamed of illustrating for those magazines. I started sending postcard mailers, month after month, to no avail. A lot of it had to do with an under-developed style, I’m sure. But I kept at it, fueled by my passion for the outdoors.

Soon enough, I got my first assignment for Climbing, and after a few years I became Senior Illustrator at that magazine. It would be a long time before I made enough money to call it a career, but this was my start. I began with the one thing that I loved enough to focus my whole being on, and this led to more. The point isn’t to pigeon-hole yourself (“Oh, he’s the unicorn guy. He only draws unicorns, but he draws them really well.”), but to use the experience as a launching point for bigger, more diverse things. But a little focus in the beginning surely helps. At least it helped me.

Start with what you love. Most people don’t realize that the knowledge they have about something that they are passionate about, the years spent memorizing information, physical skills developed, expertise, is all a marketable commodity. You have made an investment of time and energy, so you might as well put it to good use. For instance, Climbing does not hire illustrators who aren’t climbers. You really need to know the subject matter in order to illustrate it accurately. That alone narrows the field down greatly. If you know the subject, you have a leg up already.

It’s a simple point, but sometimes we get so caught up in what we think we should be doing, rather than starting with the basics and doing what we know. It’s really easy to feel like a failure if you’re not illustrating for the New Yorker straight out of school (or ever), as that is what they fill our heads with in class (the New Yorker being the ultimate culmination of our art form, apparently). Believe me, there is A LOT more out there than the New Yorker. Things take time. Build that portfolio with work you care about, slowly…and things will happen.