Looking south towards the entire Latok Group from the team?s basecamp on the north side of the Choktoi Glacier, with Luisa Giles (right) and the assistant cook, Furman (left), on the moraine above basecamp. [Photo] Jacqui Hudson

During the summer of 2007, three women–Luisa Giles (British, 25), Sarah Hart (Canadian, 27) and Jacqueline Hudson (Canadian, 28)–attempted a new ca. 950-meter free rock line in the Karakorum Range of Pakistan. The route is on a possibly unclimbed 5200-meter rock peak, on the Choktoi Glacier, in the Latok group. The peak, on the south side of the Choktoi glacier, is situated east (down valley) of Latok I’s famous North Ridge.

Luisa Giles leaving the belay on Pitch 13, during the team?s second attempt on the peak. Shortly after it started to snow, and they turned around. The Choktoi Glacier is visible below. [Photo] Jacqui Hudson

Seizing one of the few weather windows that summer, Giles, Hart and Hudson attempted the peak three times, the third over the course of three days. They climbed 900 meters up a series of granite corner and ledge systems on the peak’s east face. Fifty meters short and a couple hundred meters lateral of the true summit, they turned around, having free climbed nineteen full 60-meter rope lengths. The route offered many fantastic pitches of 5.9 and 5.10 climbing, and roughly 300 meters of simul-climbing over moderate terrain to reach a northern sub-summit at ca. 5150m. They called their progress The Partition (TD 5.10b). Due to time constraints and an estimated absence of quality climbing remaining, the team stopped at this high point and descended.

The new climb ascends the sunlit face on the right hand buttress to a point just short of the true summit. [Photo] Luisa Giles

The unnamed peak is the second (westernmost) of two similar north-facing rock buttresses joined by a high col and an ice couloir. The other buttress holds the Indian Face Arete (5.10 A3), which Doug Scot and Sandy Allen established in 1990.

Jacqueline Hudson is currently on the scenic route though a five-year residency in Anesthesiology with the University of British Columbia, in Vancouver, Canada. In the past she also managed to convince the same school to grant her a BSc in Immunology and a Medical Degree, despite principally spending her time on rock and snow. Jacqueline enjoys free, aid, ice and alpine climbing, and escapes Canada when possible to broaden her practice of medicine overseas. She tells the story.

PART I

“I need your knife.”

“What?”

I dusk-dream, clipped in at the belay, while Luisa fights with our stuck rope 20 meters above. Sarah belays her out on our other line. I stare down, across the Choktoi Glacier almost a kilometer below us, and watch the slow-moving clouds swirl north over 8000-meter peaks to the east, where they are swallowed by the dry air of Western China.

After so many days of snow and rain during our early time in basecamp, the weather finally has stabilized. When we first arrived on the Choktoi we had three days of fantastic weather. We made our first attempt then, but we were anything but acclimatized, so when the weather turned foul, we retreated. After more than a week of rain and snow (and a second attempt on the route, denied again by poor weather), blue skies finally split the clouds. Our cook, Abbas, a man who has lived his entire life in the Karakorum, told us that we now had four days of good weather before the next storm. We did not have a working satellite phone or a reliable altimeter–something we discovered only after arriving in basecamp. Abbas was the best weather report we had, and his prediction would be right.

“I need your knife!”

Sarah Hart (left) setting up for the next rappel while Luisa Giles (right) finishes off the seventh rappel long after dark. [Photo] Jacqui Hudson

“Ok, ok, lower me your free end of rope.”

It is the end of our third day of stable weather, and we’re making our first rappel. I feel like I watch it all happen, just an observer. I force this sensation of detachment because my stomach is cramping and my body is shivering. Yet I am neither hungry nor cold. Perhaps I am both. We have been trying to free our rope for the past ninety minutes, and the sun has nearly disappeared.

Our bivy gear is low on the wall. We left it there after spending our first night on a series of ledges. We went lightweight even to the bivy: no stove, minimal water, and only a small amount of extra clothing. With our only real warmth for the night still far below us, we’re feeling more than a little vulnerable.

PART II

The air is heavy with the heat of Islamabad. The night smells of cardamom, two stroke engines, and cotton soaked with human sweat. We feel the artillery (there is no sound yet) shake the windows of our hotel room.

After a month in the mountains and a seven-hour drive from the road-head at Askoli (access to the Baltoro Glacier) to Skardu, we are greeted by the start of the pavement, and rainbows. [Photo] Luisa Giles

We’ve been traveling for days, around half the world, away from cool, temperate, sedate Vancouver (where, back in December, my program director reluctantly granted me two months to climb here).

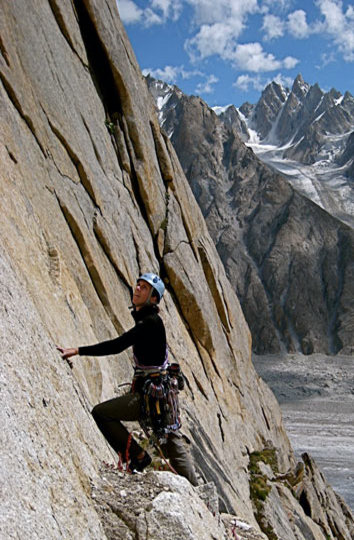

Luisa Giles heading up Pitch 16, one of the final headwall pitches before reaching the upper ridge crest. The true summit is far beyond the sub-summit seen here. [Photo] Jacqui Hudson

With me now are my two partners–finally sleeping quietly, after so long in airports, airplanes, and buses. Luisa is an energetic British ex-pat who now makes her home in Vancouver and cycles over 200 kilometers every week to work and back. Sarah is quieter, more introspective, a recent and already very competent convert to alpine climbing from a path previously focused on bouldering and competition sport climbing. I asked them to join me on this trip to Pakistan because they are wonderful women, and happen to be pretty damn good at “getting the rope up there.” They also could drop everything to fly into the unknown for two consecutive months.

We couldn’t be farther from Vancouver. It is 4 a.m. on July 11th, and the stand off at the Lal Masjid Red Mosque in Islamabad has come to a peak. The government has decided it has had enough and is leveling the place. My half-asleep brain tells me there is little I can do except believe what the hotel staff told us the previous evening: “Red Mosque is far away from the Hotel.” This claim was clearly a lie, or at least a loose interpretation of the term “far” with respect to artillery.

We survive. More than 100 people inside Red Mosque do not.

We also survive the Islamabad-Skardu flight on “Perhaps It Arrives” Airlines, better known to air traffic controllers as Pakistan International Airlines, escaping the very real possibility of crashing into Nanga Parbat. And out of some western, idealized madness, we have left our nice stable jobs, our comfortable existence with espresso coffee, socialized accessible medicine, working traffic lights and people who obey them, to come climbing here. Why? Good question.

PART III

“The knife!”

Breaking out of my forced dreaming, I tie the knife I keep around my neck to the rope’s end for Luisa. We’ve tried coaxing, flicking, pulling (so hard we burned our hands), levering and hammering to free our rope, to no avail. In the end, we lose only five centimeters of rope–but also two hours of daylight. We tie the tattered ends together and finally continue moving down. The sun sinks behind the 7000-meter frame of the Ogre to the west, and its long shadow overtakes the Choktoi Valley.

Sarah Hart managing the rope on another after-dark rappel. The brown rope shows scars of its courtship with the flake on the first rappel of the descent. [Photo] Jacqui Hudson

A full moon rises and walls of granite glow in the nighttime light. Although cold, we’re steadily moving down the wall, and my earlier feelings of apprehension wane as we progress back to our bivy. By 11 p.m. we are at our ledge again.

PART IV

After two months of spending every minute with each other, night after night, close enough that we could hear each other Cheyne Stoke breathe through endless hours of poor sleep at altitude, we returned to Vancouver and our separate lives. Instantly we felt the separation, and missed each other terribly.

There were many instances during our time in Pakistan where we felt particularly exposed: our first morning in Islamabad; the reality of being without any reasonable method of contacting the outside world from the Choktoi; our rope stuck at the top of a 5200-meter peak. But we communicated well without egos, and we openly expressed our fears. I wonder if our approach to troubleshooting through our more challenging times, and the subsequent strengthening of our friendship, was facilitated by the camaraderie of women. Our challenges were not, of course, unique to us being female, but were the methods we invoked to deal with them?

Sarah Hart facing up to the start of the upper headwall, during the team?s third and final attempt on the peak. This was the start of Pitch 14, the crux pitch: 60 meters of sustained 5.10 climbing up thin corners on superb granite. Basecamp is tucked under the peaks visible on the far side of the glacier. [Photo] Jacqui Hudson

After returning to work, I was discussing the topic of gender roles–specifically women entering into traditionally male dominated arenas such as alpine climbing and medicine–with a female anesthesiologist mentor. As she set about taking control of all the physiologic functions of the anaesthetized patient on the table in front of her, she simply said, “Not until men can carry a pregnancy to term will we ever really be equal.”

She has a point; there are some fundamental differences. How far these differences affect our abilities and persuade our judgments is difficult, maybe impossible to say.

PART V

On the bigger screen of alpine climbing, our little route on our no-name peak might be a rest-day outing for household-name alpinists, male or female. But to us it felt challenging, real. Before we left for Pakistan the prospect of putting up a new rock route longer than a single pitch was a far-fetched ideal. We are, by all accounts, “small fries” who keep too many “paid rest days” per year to ever register on the climbing radar.

But our ability to work as a team, listen to one another and communicate our differing perspectives allowed us to surpass our own expectations of what we thought capable. Perhaps our commonality as women allowed us to form a firm, solid, trusting relationship that gave us a wild ride and a safe descent.

Or perhaps it is the nature of climbing to facilitate these kinds of trusted relationships. Maybe it was just a fortunate melding of compatible individuals, facilitated further by similarities that allowed us to get out there, and up there (at least most of the way).

Luisa Giles making it look easy atop a boulder close to base camp on the Choktoi Glacier. In the distance is the junction of the Choktoi with the Pangma Glacier; clouds hide The Flame and the backside of Uli Biaho, visible from basecamp during good weather. [Photo] Jacqui Hudson

I don’t have an answer. I can only reflect now on my memories of our trip to Pakistan: the sound of our cook singing in the still morning air around basecamp, the evening light on the Choktoi after a storm had passed, and the smiles and laughter of Luisa and Sarah as we climbed yet another splitter pitch of alpine granite. Philosophy aside, I can safely say I love climbing, for the people I meet, the places it takes me, for the lessons it teaches me, and the questions it makes me ask.

Looking west up the Choktoi Glacier at sunset. The Impressive North Ridge of Latok I (7145m) and the east face of the Ogre (7285m) are visible to the left of the setting sun. [Photo] Jacqui Hudson