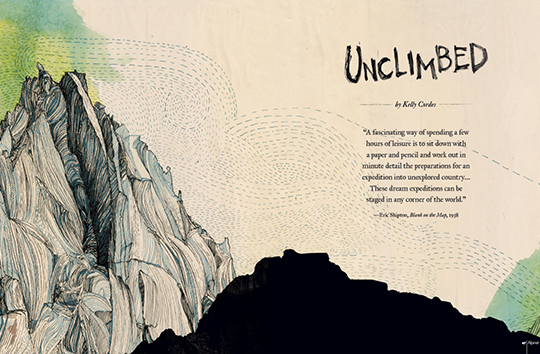

[Illustration] Jeremy Collins

Repeat number ten thousand, eight hundred, seventy-six: Old codger bemoans today’s overrun mountains, how it’s all been done, and how true adventure is dead.

An example from a travel writer named George Kennan: “It is becoming more and more difficult every year for the adventurous traveler and the enterprising student of geography to find a new field for exploration and study–or even a field about which anything new can be said…. The civilized and semi-civilized parts of the globe from North Cape to the Cape of Good Hope, and from Alaska to the Strait of Magellan, have been overrun by an army of tourists, and described in a multitude of books.”

That was 1883, in the august Journal of the American Geographical Society of New York.

Perhaps yearning for some imagined, glorious past is bound to an inability to see the future.

Surely, everyone knows that human ingenuity never ceases and that human capabilities ever evolve. But, like Kennan in 1883, we have trouble, at times, envisioning the future, determining what constitutes new, what has long been known and what has yet to be explored. Our myths and preconceptions too often constrict what we notice, and therefore, what we seek.

Perhaps no place in the alpine world exemplifies these continual transformations better than the Chalten Massif in Southern Patagonia, where sharp spires jut from the junction of the gentle estepas and the frigid ice cap. In 1959 only a handful of climbers had visited the massif; it was a legitimate, weeks-long expedition even to reach its base. Yet upon receiving a report of Cesare Maestri and Toni Egger’s supposed first ascent of Cerro Torre, the American Alpine Journal editor noted: “Our correspondent, Sr. Vojslav Arko, points out that with this ascent, the Golden Age of Patagonian mountaineering has ended.”

Notwithstanding subsequent evidence showing that Maestri and Egger had climbed only 300 meters, you have to laugh at the absurdity of Arko’s declaration. Only it didn’t seem absurd at the time. Cerro Torre had long been deemed impossible–at least until its actual 1974 first ascent. Then in 1986 the Argentine government built a bridge over the Rio Fitz Roy to enable access to an empty plot of land, designated as the town of El Chalten (established for geopolitical purposes in a border dispute with Chile). People came. Climbers climbed. Come 2008, the daunting spires of the Torre group were enchained in a single outing. With that feat, the Golden Age clearly ended. The 2012−2013 season delivered further proof when the first ascent route on the “impossible” mountain became a freeway, and more than 100 climbers stood atop the summit. It was like Chamonix without the lifts.

Imagine what Kennan or Arko would think.

Now, surely, all the obvious lines of the massif have been climbed. We–the royal we–mean it this time. The Golden Age is finally over.

Wait. Have you ever wondered why, despite the endlessly new sitstarts, variations, linkups and speed ascents, no one has climbed the south face of Cerro Torre from base to summit–much less done it free or in alpine style? OK, if today’s alpinists aren’t strong enough, brave enough or skilled enough to handle the brutal conditions and loose rock (by the way, Slovenian and Italian teams put up routes high on the face back in the 1980s and ’90s), what about the swaths of untouched rock on the east face?

Look left and right of existing lines–or venture away from the compact and easily accessible Chalten Massif–and you’ll find that countless untouched objectives still rise in the space between the grasslands and the Pacific fjords.

This story repeats itself. Simply change the names and places.

But let’s be clear: The best of those secrets won’t magically pop up like a prize in your drive-thru fast-food meal. They aren’t likely to shine in the pages of some PR person’s glossy brochure, either. Or even in a magazine article about unclimbed routes. You have to think creatively, to put in the work. When I was an American Alpine Journal editor, I’d get the occasional email that went something like this: “I haven’t been to this range, but I know you have, and you report on it, and I know that you know that you know that I know that you see lots of photos and know lots about the area. Can you tell me the best lines–we’re gonna get a grant, go climb some of ’em. Unclimbed routes only, please.” I’d chuckle and hit delete. You’re on your own, Broseph.

In 2001 and 2003, as the AAJ was going to press, my climbing partners and I were tying in below unclimbed lines on Thunder Mountain in the Alaska Range and on Nevado Ulta in the Cordillera Blanca. In both cases, our new routes were visible in photos about to run in the journal–I’d seen them while editing stories, cooking up plans from my desk. Were I a stockbroker, I might have been busted for insider trading.

Regardless, whether it’s through scrupulous research (even if looking at photos just happens to be part of your job) or through old-fashioned time in the hills, the rewards usually come to those who are on the hunt. As you come to know a place, your vision changes. You start to see things; you begin to unravel mysteries–the way that a seemingly blank headwall reveals climbable features in changing light, or how some rare flow of ice forms during specific patterns of weather. But only if your eyes remain open, because, at the same time, complacency lurks. How often have we seen hungry first-timers show up in a range and snag the goods while inveterate veterans lie in wait?

Don’t trust anyone who tells you it’s all been done. They’re either an outright poseur (as if the barstool didn’t tell you), or you’re being sandbagged.

Our hyper-connected, ever-shrinking world remains a big place. Have you ever looked out the window on the flight from Islamabad to Skardu and gazed across the Karakoram? Or stared along the Coast Mountains of Alaska and British Columbia? Have you studied the “climbed out” Ruth Gorge on your flight to the glacier or in photographs in the magazines?

Ahhh, the scarcely tapped Hayes Range, the secrets of the Kishtwar, the mysterious Muzart Gorge, the endless hidden nooks of the Siachen and Tierra del Fuego, and those remote Greenland fjords. If you possess even a shred of imagination, you know that exponentially more unclimbed terrain exists than not. What’s been done in the alpine is like a single star in the solar system.

This much is true: members of every generation, at every step, have thought they’d bumped up against the limits of possibility. In their time and place, they may have been right: at one point, 5.10 was unattainable, and 5.11 appeared blank and holdless. Many of the existing classics once seemed unthinkable. The Golden Age forever reemerges as climbers race ahead with newfound visions and abilities. My hunch remains that we’ll get lazy and afraid long before we run out of great lines.

And yet the mountains themselves are not expanding; they remain a fixed resource. (Granted, with global warming, glacial recession might add a few shitty pitches to many alpine objectives.) In Alpinist 28, Joe Puryear addressed the common, mistaken lament, and he reframed it in important direction:

I used to wish I’d been born thirty years ago, so I could experience the great mountains before all the lines were drawn on them. But I now know, in fact, there still exist many large, untouched peaks in the greater Asian ranges. We are only limited by our own perceptions and those of others.

The how of the ascent is critical to this paradigm shift. I climb alpine style to travel as lightly as I can. Instead of fixed gear or tat, whenever possible, I make V-threads and pull the cord through. That way, the next climbers won’t even know that I’ve been there; they, too, can have a mountain without any garbage or old fixed ropes, without the human impact of long sieges.

One of the greatest aspects of our pursuit is that any route can feel unclimbed if previous ascensionists leave no sign of their passage-regardless of the style in which they chose to climb. Too often in the past, climbers have strewn trash about the mountains, causing future visitors to trip over abandoned ropes, gear and garbage.

I view with suspicion those who venture into the mountains only to spoil their grandeur: Don’t our actions toward the things we profess to love say something about who we are? I’ve long seen truth in this line from Voytek Kurtyka: “If there is such a thing as spiritual materialism, it is displayed in the urge to possess the mountains rather than to unravel and accept their mysteries.”

Climb with minimal trace, and those who follow your vision might still receive the gift of newness. A well-known story about the late Mugs Stump captures this ideal. Stump had a recurring dream that he had completed, alone, one of the finest lines in the Alaska Range. He’d left nothing behind and kept the experience to himself. One evening in a bar, some climbers arrived, energized by a well-earned first ascent. Others joined in the celebration, hearing stories about the route, the very same line Stump had soloed. In his vision, he quietly joined in, raising a toast to their success.

[This is the introduction to a series of essays of unclimbed peaks and routes published in Alpinist 49. For another collection of alluring unclimbed objectives, see The American Alpine Journal’s Web feature–Ed.]