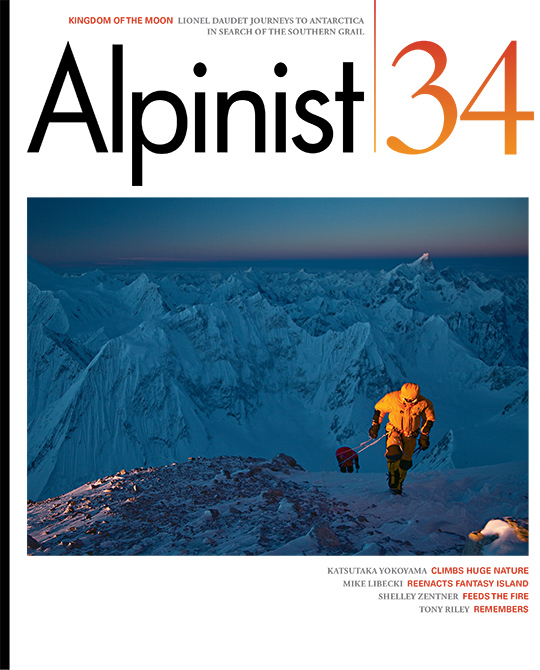

Named National Geographic Adventurer of the year in 2012, Cory Richards strives to capture both the essence of adventure and the beauty that lies at the core of our modern world. In his pursuit, Richards has traveled around the world, and in the process he has placed himself in extremely uncomfortable situations, all in the name of capturing photographs that display our common humanity. A regular contributor to Alpinist and an accomplished climber, Richards is a master of the uncomfortable. In 2011, along with Simone Moro and Denis Urubko, Richards completed the first winter ascent of 8035-meter Gasherbrum II. A photo of the ascent appeared on the cover of Issue 34, along with an editorial about the effects of new media and digital innovation on modern alpinism. “A Tribute to Discomfort” is Richards’ artist manifesto.

A Tribute to Discomfort: Cory Richards from Blue Chalk on Vimeo.

[The following editorial was originally published in Alpinist 34.–Ed.]

The Desert of the Almost-Real

“The fact of storytelling hints at a fundamental human unease, hints at human imperfection. When there is perfection, there is no story to tell.”–Ben Okri

JANUARY 2010: Frost builds on my stubble. My fingertips lose color and go numb. The small patch of light cast from my headlamp seems dim against the immensity of the frozen Himalayan night. As I start to shake, I bow my head and focus on my breathing. I struggle to stay warm against the biting wind.

I’m only three feet away from my tent on flat ground at 5243 meters on the South Central Buttress of Tawoche (6501m), clutching the battery pack of a dying satellite modem, like an emperor penguin coddling its egg. Renan Ozturk reads out loud the percentage transferred of the video dispatch we’re trying to upload–one of many extra acts we’ve added to an already-demanding alpine climb. Why? And to what end? I’m tired.

I peer up. Renan’s face is twisted with exhaustion. The vapor of his breath swirls in the blue glow of the laptop. He blows into cupped hands and shakes them wildly. He hisses through clenched teeth. His fingers fumble at the keyboard, as if picking at mandolin strings. Around our base camp, amid the clutter of ropes, racks, ice tools, crampons, boots and food, other curious items surface: multiple laptops, cameras, a dolly, a crane, some microphones and sound-recording equipment. I feel disoriented. My eyes lose their focus. The world starts to go soft. Renan’s voice is little more than a whisper above the wind.

BEFORE THE EXPRESS COMMUNICATION of the digital age, climbers disappeared into a vertical wilderness as silent and isolated as the depths of space. Runners carried the news of the largest national Himalayan expeditions down the flanks of the mountains and out to the towns where it could be radioed to newspapers around the world. After the 1960s, some mountaineers were able to radio updates from advanced base camps. But most climbers shared their stories well after the experience itself. Emerging from weeks or months without contact, they labored over articles, films and books–or simply told tales around the campfire.

For modern alpinists that kind of seclusion is now elective, not mandatory. Even in remote places, climbers can capture scenes in high-definition video, blogs and photos with relatively light and inexpensive equipment– and then post them quickly for the entertainment of crowds staring into computer screens at home. As technology grows more sophisticated, the images become more potent, immediate and seemingly real. At the same time, the quality of reproduction increases the potential that made-for-media ascents could eclipse other perhaps more genuine–but less professionally recorded–adventures.

“Video is seductive and pleasing, so to those who are less informed, a well-documented climb that is of little significance seems to be more important than a truly impressive climb that produced only crude photos,” alpinist Colin Haley points out. “There is no doubt that digital media will be captured more and more on harder and harder routes, but I think that today the best climbs are in a realm where there is no room for video cameras and satellite phones.”

THREE HUNDRED METERS BELOW the summit of Tawoche, I’m haunted by Colin’s statement. Renan’s yellow boots, clipped to his harness, bounce off his hip as he struggles to balance onto a high-step. The weight of his pack makes his right foot tap against the steep slab, giving him the extra bit of purchase he needs to stand up on his left. His breathing sounds forced. I know his mind is straining to get his dehydrated and exhausted body to move. And while I recognize that we are not on a “cutting-edge” alpine climb, we are nonetheless exploring technical new terrain at altitude in the heart of the Himalayan winter. Is there room for media here?

As I watch Renan grapple with the crux moves of the route, I juggle brake hands, placing the rope in my left so I can operate the camera with my right. My sole focus should be on the leader. Isn’t that the rational thought? But I’m certain I can manage to belay him safely and still get the footage. I flip the digital camera with my thumb, activate the live-view feature with my nose, toggle to manual-exposure mode with my teeth, and press Record. The days of cumbersome broadcast cameras and stacks of film are over. We’ve left the laptops, the satellite modem and the heavier equipment at base camp. For now we’re shooting in the moment–moving in alpine style and in almost real time, searching to define our own shifting and elusive balance between action and documentation.

I’M STILL NOT CERTAIN where that equilibrium lies–or how the arts of alpine climbing and storytelling could evolve with some cohesive ethos. “Why does one climb? Is it for the experience itself, or for the story that may be told about that experience?” Canadian alpinist Raphael Slawinski asks me from his home in Calgary, Alberta. “Fundamentally, there is nothing wrong with either motivation, but they are very different and should not be confused. In particular, the worth of a climb and of the story that may be told about it are not necessarily related.”

“Significance” (pace Colin) may arise from ascents that have little technical importance. The adventure writer Tim Cahill is hardly an elite alpinist. Yet he recorded his humble forays into the mountains in meticulously crafted prose, because he believed that vivid, dramatic storytelling could “enlist readers into a gentle conspiracy of caring,” enticing them to love the natural world through vicarious adventures–and later to explore it on their own.

Stories of all kinds draw so many of us into the wild for the first time. When I was a bored child, my father handed me Straight Up, the classic biography of the alpinist John Harlin II. He said he’d pay me five cents a page to read it. I opened the book, and the next thing I knew, I felt as if I were halfway up the Eiger Nordwand. My eight-year-old mind swam against the current of a raging blizzard. Two hours later, I reeled from the death of my imaginary climbing partner. Not until I read the final word did I set the book down. By then, the faded white canvas hardback appeared as tired as I felt: worn by small, sweaty hands, the pages slipped from the binding.

I asked my dad for another book. He led me up the staircase to my parents’ bedroom and pointed at the shelves. Everest the Hard Way; K2, The Savage Mountain; The Boardman-Tasker Omnibus…. The canon was all there. Soon more words flooded my mind with images: streams of azure ice ribbons on the great walls of the Himalaya, storms and avalanches below the summits of the world’s grandest peaks. How could it be dinnertime? Can’t my parents see I’m in the middle of a terrifying and demanding lead? Gradually, these dreams of childhood evolved into the aspirations of my grown-up life.

NOW MY FRONTPOINTS COME TO REST on one of Tawoche’s delicate crystals. I lift my left foot and step through gently, taking care not to snag my crampon. I’m over-gripping the ice tool in my left hand. My right searches blindly for purchase on a granite slab. Anything will do. I’ve tucked my chapped face into the opening of my unzipped jacket. As I exhale, my glasses fog. I can’t see anything. Panic surges. I’m twenty chossy, mixed feet above Renan, with no gear in. I don’t want to fall.

I wriggle my mouth and nose out of the jacket and gasp. My glasses clear. I place a foot on a ledge adequate enough that I can take my right tool from my harness. Swinging into ancient blue ice and moving up, I’m relieved. Then all at once, the rope comes up short. I realize the camera is rolling. It has been the whole time.

When I look down, Renan turns the camera off and feeds me line. That must have been incredible footage. My mouth is dry. I can’t swallow.

Later, as we piece together the same capture, the anti-bot plates on the bottom of my crampons make conspicuous bright orange shapes. Did we design it that way? The moment manifested by chance out of the challenges of the climb and my own engagement with the mountain. Will our sponsors be happy? You bet. Was my experience “authentic”? I still can’t swallow. Have we told a story or created an advertisement? I don’t know.

NEW-MEDIA STORYTELLING lures audiences into websites, creating a flow of traffic to sponsors’ brands. To capture a core user group, manufacturers need their gear to be as visible as possible within an authentic-looking context. The rapidity with which the Internet delivers the videos and photographs of an ascent gives the illusion of images that are more raw, immediate, uncontrolled than those of print. There’s less time, it seems, for censorship or embellishments. Yet “real time” or “almost real time” is just a concept: it doesn’t erase the possibility of editing moments into an effective sequence, conveying whatever message you want and eliminating any extraneous–or possibly unflattering–details. The Internet merely shortens the temporal gap between the experience and the portrayal.

MY LEGS ARE BURNING. I run down the talus slope. Each step takes me farther from the serac runout zone. My camera bumps against my side. I want to stop and film Renan as he trots down behind me, his body clumsy from exhaustion, but this is no place to pause. At last, we collapse on top of a boulder. After the long descent of Tawoche, we have only twenty meters of tagline left, along with half our rack and no food. I lie in the sun, panting and drenched with sweat. My grimace softens to a smile: four days since we left base camp, including thirty-six hours without water, we’ve completed a new route on a 6000-meter peak. I reach for the camera, but Renan has beaten me to it.

I close my eyes to play back the “A-Reel” in my head. The memories of the climb are cut like a film–a home movie only I can see. Dust lines my mouth. My fingers throb in unison with my burnt lips. But the pictures in my mind don’t only exist there.

Months later, watching the film, I wonder whether I’ve compromised something–the experience that alpinist and photographer Marko Prezelj calls “the pure feeling of being concentrated in the certain moment without thinking how this will look for others.” To that point, he asks, “Are the feelings (and our behavior) making love the same if we know that someone is watching us or even filming us?”

GREAT ART HAS ARISEN from the close observation of ascents in the past, from climbs both relevant and irrelevant by the standards of their day. The elegant black-and-white photographs of Vittorio Sella; the spare, lyrical words of Gaston Rebuffat; the rapt, ascetic sculptures of Andy Parkin; the flickering old movies of the earliest filmed adventures–all appear to convey something at once momentary and timeless, immanent and transcendent. The stories they tell aren’t limited to strict historical accounts; there’s that extra, “unnecessary” element of beauty. The “ecstatic truth,” as filmmaker Werner Herzog names it–the portrayal of some inner, essential meaning–is not always the same as the minutia of external reality. An aura still seems to cling to their work that speaks to the “spirit of alpinism.”

Do those slower forms of creation illuminate that spirit more naturally, out of the detachment, immersion and solitude that they allow? Or are we merely romanticizing the old days? The spoken and written words of that bygone era could be just as easily manipulated as the digital images and HD film of our time. Economic and political concerns drove the propagation of some of the earliest ascents, at times resulting in the distortion of facts, as many well-known controversies and revisionist histories attest. Historians needed time to expose the fundamental shortcomings of the older exploratory documentation. Perhaps our community also required that distance to think critically–to develop a philosophy and a standard of accountability. The technology of communication may have advanced too rapidly in recent years for our understanding to keep up with it. We’re still scrambling to determine aesthetic and ethical guidelines in the age of social media. Maybe what I’m now looking for–what we should all be searching for–is a new set of narrative ethics, a new grammar of style, to define the artistic and journalistic integrity of these evolving forms.

Some aspects will remain subjective, according to the vision of the participants. Ultimately, however, honesty is what matters in both alpinism and in storytelling. The questions for both activities become the same: What were the tactics used to achieve the climb and the representation of it? Did you alter the route–or the mountain–in any way to facilitate a pre-scripted storyline? Did you climb in a heavier style or put yourself and your partners in danger in order to document the ascent? Did you drill more bolts than you would have normally placed? What was your intent? Did you edit and organize scenes to highlight a product or to promote yourself? Or did you do it to communicate the spiritual, aesthetic, elemental qualities of the pursuit? To contribute to an accurate historical record for the future? To push yourself as a climber and an artist to create something as true and beautiful as possible? To celebrate the fusion of two passions?

Whether you’re telling a video story from the field or writing a book about it years later, all narrative derives from struggle, flaws and self-doubt. Since humanity’s first myths, the storytelling impulse has represented a desire to find meaning in the natural world, to give structure and order to an experience of chaos. Art results from the shaping of arbitrary elements of reality. Every form of language and expression forms a wall between the climber and the direct experience. The paradox of all media is this: the means we use to break down the boundaries between our solitary perception and the imagination of an audience creates a barrier in and of itself.

PERHAPS THE PURE CLIMBING experience exists in a realm not just beyond digital cameras– but beyond all forms of communication. The perfect story is the one that’s never told. In the end, however, the great, imperfect tales are all that we can strive to create, and all that we can hope to share.

Purchase a copy of Alpinist 34 where this story first appeared here.