[This story was first published on pataclimb.com on February 2, 2015.–Ed.]

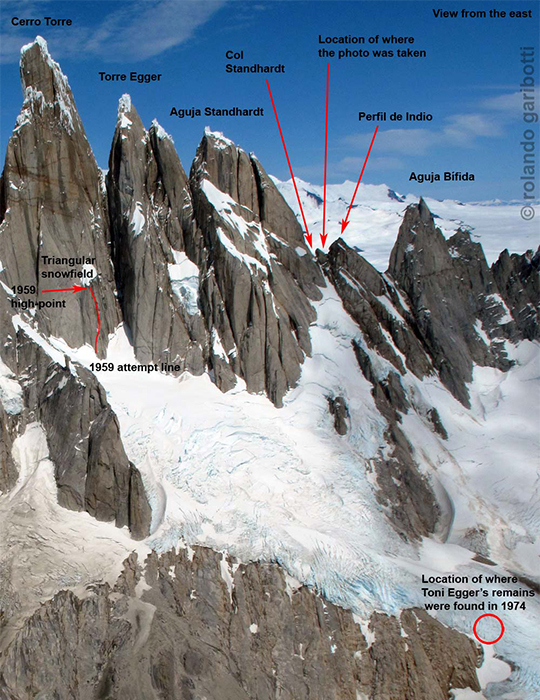

Over the past four decades, Cesare Maestri’s claimed ascent of Cerro Torre in 1959 with Toni Egger has been widely discredited (*). An abundance of evidence has shown that their high point was only a quarter of the way up, 300 meters, near the so-called “triangular snowfield.” What has remained a mystery is where Egger and Maestri (supported by Cesarino Fava) actually went during the six days that Maestri said their round trip required, and from which Toni Egger never returned.

Maestri was undoubtedly a phenomenal climber and an independent thinker, a vanguardist who deserves respect for his contributions. However, this should not preclude examination of his Cerro Torre claims. In doing so we are trying to establish the facts relating to the first ascent of one of the world’s best known mountains. To this day, nobody has ever mounted a fact-based defense of Maestri’s 1959 Cerro Torre claim, countering the contradictions, inconsistencies and evidence piled against his story.

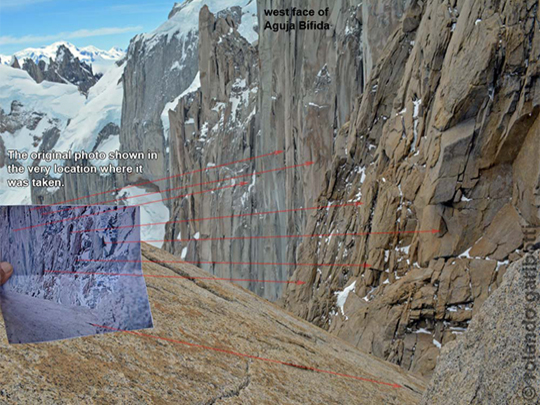

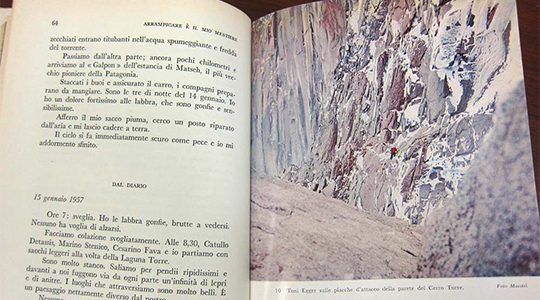

But proof of Egger and Maestri’s whereabouts during those six days was out in the open all along. The previous days of the expedition, with the team portering gear, making day trips to the lower east flanks of Cerro Torre and fixing ropes to the triangular snowfield, were all accounted for and corroborated by Fava’s journal, the journals of the three young college students who accompanied them on the expedition and by Maestri’s own accounts. In Maestri’s book Arrampicare e il Mio Mestiere (Milano, Garzati, 1961) a photo (on a non-numbered page, adjacent to page 64, effectively page 65) taken by Maestri shows the late Toni Egger climbing on what the caption claims are “the lower slabs of Cerro Torre’s wall.” Two years ago Ermanno Salvaterra and I had noticed the photo while working on a yet unpublished book; Ermanno and I knew the terrain, and it was clear that the photo had not been taken on Cerro Torre. What remained unclear was the actual location. The photo had been cropped in such a way that very little of the background could be seen. About a year ago Kelly Cordes asked me to look into it again, and he recently insisted, so I put forth a more decisive effort. After many hours studying images of the entire valley, with the help of Dorte Pietron, we recognized a feature that matched the photo in question. Bingo!

[Photo] Rolando Garibotti

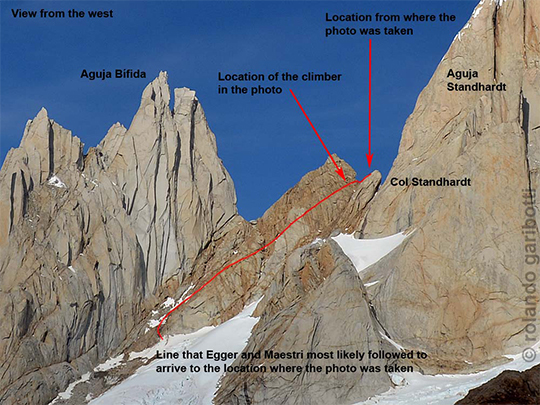

Maestri’s photo of Toni Egger was in fact taken on the west face of Perfil de Indio, a small tower north of the Col Standhardt, between Agujas Standhardt and Aguja Bifida, on the west side of the massif, the opposite side that they claim to have been climbing on.

What is the significance? In Maestri’s many accounts of his 1958 and 1959 expeditions, never does he mention climbing on the west side of the massif. The six days when Maestri claims that he and Egger made their final push on Cerro Torre from the east are their only unaccountable days. What really happened during those days? This photograph provides another piece of evidence, and unequivocal proof of a place they went during their expedition that, curiously, Maestri never mentioned. Indeed it is nowhere near the location of his claimed ascent, and certainly no place one would unintentionally wander. Or forget. Perhaps in light of the massive difficulties faced from the east, the pair considered the west face of Cerro Torre, where Walter Bonatti and Carlo Mauri had found a line of weakness and made good progress a year earlier. From their east-side base camp, the only possible way to reach Cerro Torre’s west face would be to climb the slopes to the Col Standhardt, and then rappel west (decades later, this would become one of two most common approach routes to the west face). In Maestri’s photo, Egger is shown climbing below (west) and immediately north of the Col Standhardt, obviously returning to the east side of the massif. It is an impressive lesson in route finding. In the last decade parties trying to return to that same col from the west have needlessly battled with steep, hard climbing directly up to it. The line chosen by Egger and Maestri is far easier (III). From the Col Standhardt, the pair would have faced a return down the wind-loaded, avalanche-prone slopes that feed into the bottom of the Upper Torre Glacier – where Toni Egger’s remains were later found.

Toni Egger’s death remains a mystery. Based on this new information it seems possible that he suffered an accident descending from Col Standhardt. The one person who knows what really happened refuses to speak, leaving us to try to piece together the truth. The most troubling aspect of Maestri and Fava’s story is that they told inaccurate information to Egger’s family regarding his death. Upon their return Maestri and Fave did not bring back any of Toni’s clothes, equipment or diaries (Toni was well known for writing detailed entries in his diary) for his family. Toni’s sister is still alive. She is in her late 80s, living alone in a small town near Linez, Austria.

It is long overdue for Maestri to provide her, and the world, with a truthful explanation of what happened during those six days in 1959.

Toni Egger’s last lesson to us is that of clever, ingenious route finding. Hopefully Cesare Maestri’s last lesson will be one of integrity, coming clean once and for all.

What the photo proves:

– that this photo, which Maestri used in his book, was not taken on Cerro Torre as he claims.

– that Egger and Maestri visited the west side of the massif, the opposite side to what Maestri claims, likely to attempt the west face of Cerro Torre (what other objective could have possibly made them want to head that way?).

– that, because no days were unaccounted for, undoubtedly they went there during the six days when Maestri claims they were climbing and descending the east and north face of Cerro Torre.

– that the camera was not lost as Maestri claimed.

* The first publicly expressed doubts were from Carlo Mauri, a renowned alpinist from Lecco, Italy. Later the case was picked-up by Ken Wilson, then editor of Mountain Magazine. Much has been written about the many inconsistencies in Maestri and Fava’s accounts, and about what might or might not have actually happened. On top of Wilson’s excellent articles, some key publications include Tom Dauer’s book Cerro Torre: Mythos Patagonien; my article “A Mountain Unveiled,” first published in Dauer’s book, later reprinted and expanded in the American Alpine Journal; Reinhold Messner’s book Torre Schrei aus Stein; and more recently Kelly Cordes’ book The Tower: A Chronicle of Climbing and Controversy on Cerro Torre. All who examined the facts have reached the same conclusion: Maestri’s account is but a tall tale.