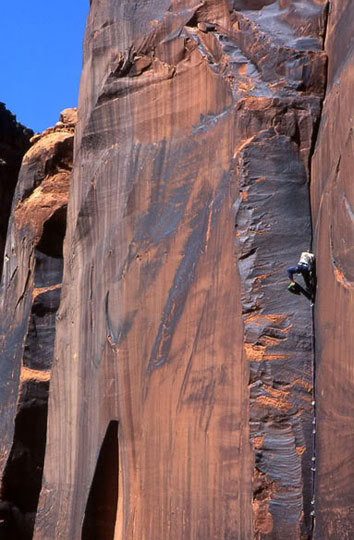

Kyle Copeland. [Photo] Todd Gordon

Kyle Copeland died on October 3 in Salt Lake City after a long battle with Crohn’s Disease. He was 51.

A naturalist, musician, geologist, computer programmer, equipment designer and artist, as well as a prolific first ascensionist throughout the American Southwest, Copeland was a renaissance man.

His list of first ascents span Boulder Canyon, Eldorado Canyon, Longs Peak, South Platte, Nevada’s Wild Granites, Arches National Park, Zion National Park and the greater Moab, Utah area. Diamond Star Halo (V 5.8 A4) on Longs Peak in Rocky Mountain National Park may be Copeland’s most revered route, but his greatest contribution to climbing came from his quiet quest for desert rock.

“Kyle was probably the best desert climber that ever lived,” said close friend and climbing partner Ron Olevsky.

Copeland’s drive and mental toughness took him up stout lines; sometimes that same stubbornness resulted in a clash of personalities. To many of his acquaintances, Copeland was anomalous and mysterious. But to those who knew Copeland well, he was jovial and colorful.

After high school, in 1979, Copeland moved from Stony Brook, N.Y. to Boulder, Colo. with hometown girlfriend Dr. Irene Good. The next year Copeland and Good had a daughter, Ianna. Good, with Ianna, then moved back to the east coast to finish college. Good and her daughter’s contact with Copeland faded in and out, but they continued to stay close with his family.

In Colorado, Copeland met fellow climber Dr. Alison Sheets. The two would remain good friends throughout his life. During his time in Colorado, they dated and climbed together. While there, Copeland sewed and designed gear for JRAT, a local climbing company. He also worked at a local gear outlet called Forrest Mountain Shop in Boulder, Colo.

Copeland’s sewing and design work impacted the gear that much of the climbing community relies on today. He reverse-engineered old designs and manufactured new packs, clothes, gloves, aiders and sewn runners for JRAT, Lowe Alpine Systems, Mountain Mend and other manufacturers. Copeland’s designs and ideas would later be incorporated into Yvon Chouinard’s Patagonia when JRAT was absorbed by the brand. His ingenuity also carried over into skills as a computer programmer. Through his skill and creativity, Copeland sold and lived off the clothes and gear he made, giving him as much time as possible to be outside.

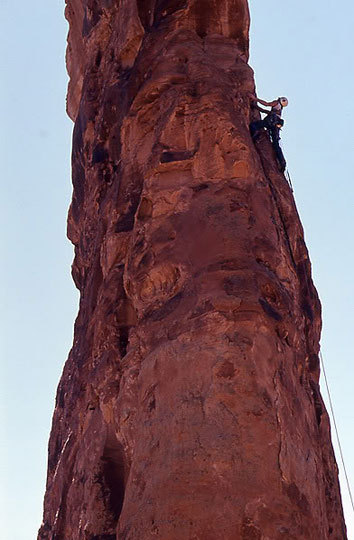

Copeland on another desert discovery, The Kind. [Photo] Todd Gordon

In the late 1980s, Copeland moved to Moab. He began to make jewelry while continuing to design gear. Most of his art was made with rock, but he also sold designs made with dinosaur bones discovered near his home. Copeland’s desert climbing knowledge also supported his lifestyle, as filmmakers occasionally hired him as a rigger for movies and commercials filmed among desert towers.

Yet it was when Copeland moved to Moab that he first was diagnosed with Crohn’s Disease. In 1988, he had an operation to resect five feet of his small intestine. Despite pain and discomfort, he continued to climb. Copeland teamed up with Charlie Fowler and Ron Olevsky to establish numerous first ascents. Olevsky fondly recounted the trio as “the Three Musketeers of the desert.”

In the early 1990s, Copeland worked with American Adventure Productions on the film Rock and Road with Fowler and Olevsky, and with National Geographic. He and fellow climber Dave Whidden also were the featured climbers in the Imax film Cosmic Voyage.

Copeland was a climbing adventurer but preferred to live life under the radar. According to friends, his personal hero was Layton Kor, who also lived “off the grid,” generally staying out of the mainstream scene.

Copeland’s personality was very much characterized by his larger-than-life climbing style. “The Kyle I knew would do just about anything to get to the top,” said John McMullen, former roommate and good friend.

“He wanted to experience the element of the unknown,” Dr. Sheets said.

Copeland on Bride, Gemini Bridges, Moab, Utah. [Photo] Todd Gordon

His desert tower climbing required both incredible strength and perseverance. It was the same toughness that kept him alive for over a decade while in the terminal stage of Crohn’s.

Eventually Copeland could climb no longer. But simply continuing to live in Moab, surrounded by his beloved landscape, kept his spirits high. His home became “a climbers’ way station,” where Copeland would lend gear and offer beta to friends and strangers.

In the last few years of his life, his strength kept him going in the face of a stroke that cost him the use of his right arm, and the amputation of one of his legs from a staphylococcus infection. To Copeland’s friends, family and admirers, the last years of his life are the most tragic and ironic for a man whose life was tantamount to independence. But they also point out that only someone as strong as Copeland could last as long he did under his condition.

Many have described Copeland as “a climber’s climber.” Modest of his skill, strength and accomplishments, his love of climbing came first. Perhaps it is for these reasons that so many talented climbers roped up with him, and that so many hold him in high regard.

Kyle Copeland is survived by his parents Charles and Jean Copeland, his two sisters Shellon and Kandel Copeland, Irene Good and their daughter Ianna, his extended family and his many friends. Shellon Copeland is organizing a celebration of Kyle’s life in Moab on his birthday, May 7.

Editor’s Note: This article was amended on October 26, 2009.