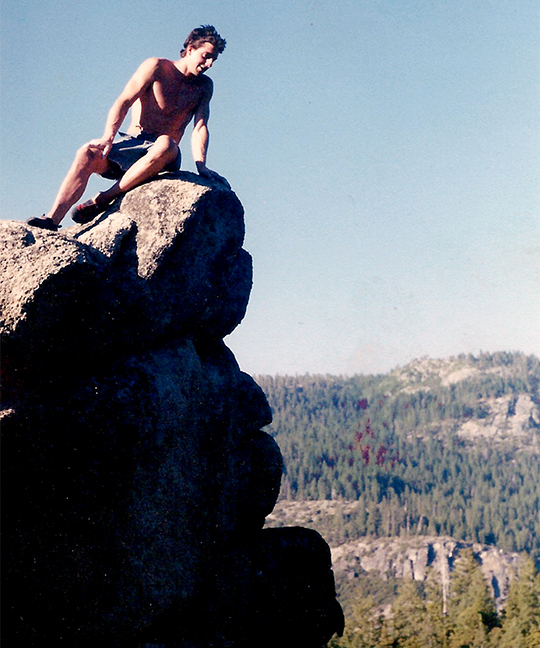

[Photo] Bryan Kay

On Saturday, Dean Potter and Graham Hunt died in a wingsuit accident in Yosemite. I’d stopped to turn my phone back on after a day of climbing when I got the message. The whole drive back alone from New Hampshire, I watched the evening sun turn the mountains into the hues of spring flowers, pale rose and gold, and I thought about how much Dean loved the “north country,” where he spent his childhood.

There’s an intensity to May in northern New England, one that has to be seen and felt to be understood. A shimmer of green spills across the landscape. Small blossoms appear on the maple and the apple trees, transforming hillsides into bursts of multicolored light. Creeks swell with snowmelt, roaring to the valleys from the heights. A feeling of inchoate promise spreads through the air–a sense of something greater, brighter, more alive, just at the edge of imagination. It is a surreal setting to be thinking about death. Yet since yesterday, everything has made me think of Dean: last night’s stars above the farm fields as I reached my Vermont apartment, this morning’s sun setting the dandelions ablaze.

Dean and I worked together for years on various writing projects, for Alpinist and elsewhere. And as an editor, you get to glimpse something of your writers’ inmost selves–those fragments of dreams and hopes and fears stirred up by the creative process. In October 2008, when the old owners of Alpinist went bankrupt, he called me immediately, even though I barely knew him, then. He told me that he knew what it was like to lose everything, and that he wanted to help. For about a month, that autumn, he hired me as a freelance editor and research assistant for a project he was then working on–and he emailed and called regularly, not just to talk about the project, but to see how I was coping, to assure me that he believed the darkest times our lives can lead to the greatest creativity, that those moments when we stare into the void are the ones in which new ideas and images flood our minds–like the lift that forms on a flying bird’s back.

He told me about a recurring dream that he’d had since childhood. Later, after he’d reached out to the new owners of Alpinist, urging them to re-hire me, he wrote about the dream for Alpinist 27:

“…birdsong filtered into my sleep. I dreamed of feathers sprouting on my arms, fields rolling far below in waves of cloud-streaked green, distorting into burnt wastelands of faint sand dunes and dust storms…. The sky cracked open. Underneath me, a blurred tunnel formed. I began plummeting, out of control. A dead tree spiked up, its branches like the hands of a corpse. My heart was beating, growing louder, bigger, as if it might detonate. I woke to its pounding and to the fading songs of birds. All my life I wanted to make the first part of this dream real, but find a way to decipher the ending.”

[Photo] Bryan Kay

He hoped that by confronting his fears–as a soloist, a BASE jumper, a highline walker or a FreeBASE climber (soloing with a parachute on his back)–he might find a way to turn the nightmare around, to transform a terror of falling into a dream of flying, to find some hidden key to change the impossible into reality, to go beyond the limits of the physical and still return safely home. He used the world “aerialism” to describe the arts of the air, and he hoped that his ephemeral creations–those dances above the abyss–might wake people up to the infinite wonder and the wildness of the world.

During those days of my unemployment when he tried so hard to look after my well-being, I thought of him as an older brother, but he was a famous climber, and I was too shy to tell him that. I remember thinking, I never want to write your obituary. I never thanked him enough; perhaps there was no way I could have. I’ve realized, now, that this might be a last act of friendship, to contribute some fragment to the many different visions of a human life, a mind, a soul. There is a tendency, after legendary climbers die, to turn them into icons, as if their great exploits summed up the whole of who they were.

But there was also the man who could sit for hours in the Yosemite springtime, wondering at the hardiness of the “little frogs peeping and croaking from beneath the snow’s surface.” Or who marveled at the simple “magic” of skate-skiing under the full moon.

There was the thinker who sifted through old books and archives looking for examples of men and women like him, early funambulists or tightrope walkers who sought to travel the line “between the material and the spiritual.”

And there was the writer who could capture the intensity of existence in tiny, electric moments–turning the experiences of walking a highline untethered, high above the Valley, or free soloing the blue-grey walls of the Eiger, into sharp and radiant haikus, blending his consciousness with everything that surrounded him, the bright air, the smooth stone, the curve of a wing or a drop of rain.

Earlier this month, I’d listened to a lecture by a British climber and poet, Helen Mort, in which she talked about how climbing resembled poetry–both pursuits appear as singular luminous moments, separate from the regular course of existence and difficult to describe.

All day on May 17, before I knew that Dean was gone, I was in Huntington’s Ravine on Mt. Washington with a friend, soloing up the easy, blocky arc of the Henderson Ridge, feeling that sense of pieces of experience put together like poetry–the rough granite beneath one hand, the edge below a foot, the thunder of distant icefall, the light flashing across alpine meadows and patches of snow. I like to think, now, that in a way, without knowing it, we were honoring him.

He lived his life like a poem.

“I want to be a part of what turns this world more soulful,” he wrote to me in October 2008.

I want to tell him that he was.

[We will be posting obituaries of both Dean Potter and Graham Hunt later this week–Ed.]