[Photo] Much Mayr

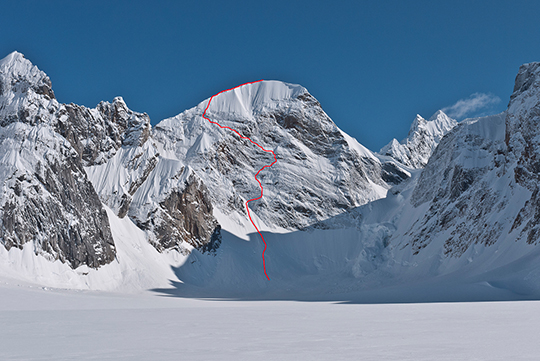

“I just went for it. There was no other option,” says the Austrian alpinist Hansjorg Auer of the crux lead on his and Michael “Much” Mayr’s May 17 climb Sugar Man (M7 85 degrees A1, 2,460′), in Alaska. Their route climbs the unrelentingly vertical ice- and spindrift-shrouded north face of a 7,425-foot peak they named Mt. Reaper, in the Neacola Range, the northernmost subrange in the Aleutian Range. Some 60 miles from civilization, Mt. Reaper is the sort of remote place, says Auer, with “less climbing activity and less information” that has long attracted him: the blanker spots on the map where adventure can still be had on its own terms. Though the peaks in the Neacolas are no taller than 10,000 feet, the glaciers sit lower than in the Revelation Mountains or Ruth Gorge, providing up to 3,000 feet of vertical relief, and many unclimbed faces.

[Photo] Hansjorg Auer

Though low-key about their skills, Auer and Mayr have quietly made difficult ascents in Europe and North America. In 2007 Auer free soloed the 850-meter “Fish Route” on the south face of the Marmolada, a technical, slabby, high-mountain 5.12c that he is the only person to have climbed ropeless. And in 2011 Auer made the first all-free ascent of the Black Canyon of the Gunnison’s Hallucinogen Wall at 5.13+ R, eliminating the unique approach of dry-tooling in rock shoes that Jared Ogden and Ryan Nelson employed on the crux pitch in 2005. Mayr, meanwhile, has freed the Salathe Wall on El Capitan (VI 5.13b) and onsighted the Westie Face of the Leaning Tower (V 5.13b A0).

This year, the two planned their trip to the Neacola Range based on photos Auer had seen in which he noted “three interesting projects on the Pitchfork Glacier.” They flew in to the Pitchfork on May 11 from Anchorage, and subsequently tried a warm-up climb on the neighboring Citadel, but retreated after 1,300 feet due to poor conditions. A whiteout pinned the pair in their tent for three days, and they worked constantly to rid the tent of snow. “I already thought this won’t be the most lucky trip,” Auer wrote in a trip report, adding that it was warmer than they had hoped for, meaning conditions on any objective could be shifty. Still, they decided to mount an effort. “Mt. Reaper looked really good from our base camp,” Auer continued. “A great wall and a nicely formed mountain. Furthermore, the wall is pretty steep, and the climbing there looked intense and straightforward.”

With only a one-day window of marginal weather predicted, the Austrians set out at 4 a.m. on May 17 with light packs and no bivy gear, knowing that they’d need to climb quickly to beat incoming weather. The north face of Mt. Reaper presented itself as a vast wall looming overhead, banded from lower right to upper left with diagonal layers of snow, ice and rock of sustained verticality. As they climbed, they moved up rock features, thin ice and spindrift, finding very little protection, as the underlying granite was nearly crackless. In places, the men belayed solely off their ice axes, and in other spots the ice was so thin and poor the second could remove the screws without even twisting them.

[Photo] Hansjorg Auer

The lower third of the wall, Auer said, was slightly easier than the middle, which was “kind of scary, because the wall is overhanging on the left and nearly vertical where we climbed.” It was here that they encountered the crux: a leftward traverse, with some aid, across spindrift and sugary small cornices after the ice became too thin to allow a more direct finish. As Auer led, he found little pro with only a sling over a loose flake, another sling that popped off because of rope drag, a Bird Beak halfway in and a piton pounded behind a small, expanding flake. “I climbed around a sugary cornice and up over an 85-degree granite face, hooking and hoping that the thin ice I saw above was solid,” Auer said. It was here that he “went for it,” with no other options.

Above, the finish was “no problem, the upper ridge more or less easy,” Auer said. The Austrians spent a brief five minutes on the summit and then raced heavy clouds back to basecamp, which they reached after twelve hours on the go. They named the mountain for the Sensemann, German for the Grim Reaper. Meanwhile, their route took its name from the sugary conditions, “lots of thin ice and only spindrift snow,” as Auer put it, which allowed them to climb the underlying blank granite.

[Photo] Hansjorg Auer

Rack: Six ice screws, seven Bird Beaks, four pitons, single set of cams to No. 3 (doubles in smaller sizes)