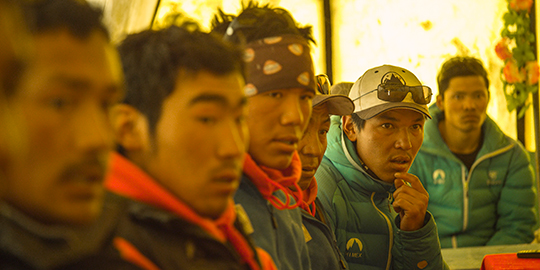

[Photo] Renan Ozturk/Courtesy Discovery Channel

It’s April 2014 in Nepal. Under an intensely blue sky, the moraine beneath the Southeast Ridge of Everest buzzes with humans, yaks and moving cargo. In short order, an expansive city of brightly colored tents rises up from barren ground, stocked with surprising luxuries. Modern-day Everest is big business, and expedition operators endeavor to make the trip pleasant for paying clients. Flat screen TVs, prepared meals, and delivery of tea and hot towels are just some of the niceties of the base camp experience. Sitting on cushioned chairs under the shadow of the world’s highest peak, visitors may rarely spend time pondering how all the stuff finds its way here, miles from the nearest village.

Multiple media production teams whirl around base camp. One crew hopes to deliver a live broadcast of a wingsuit attempt from the summit for the Discovery Channel. A second team is there to film the movie Everest, a retelling of the events from the 1996 disaster. A third group, with director Jennifer Peedom and high-altitude cinematographer Renan Ozturk, intends to document Phurba Tashi Sherpa Mendewa’s attempt to make his 22nd ascent of the mountain (more than any single individual had before). In the process, Peedom and her crew aim to showcase the realities of life on and off the mountain from the perspective of Sherpa workers, whose intense labor make nearly every supported summit attempt possible.

[Photo] Courtesy Discovery Channel

On April 18, just as the climbing season begins, a serac on the Western Shoulder collapses, launching an avalanche that washes over the Khumbu Icefall. Sixteen Sherpa and other Nepali climbing staff perish. As the news spreads around the world, the undercurrent of labor inequity, and life and death on the mountain appears inescapably stark.

Opposing Narratives

After the avalanche, the Discovery Channel scrapped its live broadcast, but the two other crews went on to release the Everest movie and the Sherpa film. The two films seem in direct contrast to each other.

The big budget Everest movie, filled with drama and special effects, tells the tale of the 1996 loss of eight climbers on Everest. It follows the well-tested formula of depicting Westerners as the central characters, and barely mentions Sherpa guides in its lengthy two hours. This is not unusual: since the release of John Noel’s documentary of the 1924 expedition, there have been over two dozen films, shorts, TV series and segments produced about Everest for Western audiences. Like the Everest film, as Karsang Sherpa explains to Alpinist, most of them seem to render the Sherpa staff “invisible.”

[Photo] Courtesy Discovery Channel

Karsang Sherpa has lost two uncles and numerous friends in Himalayan expeditions; his own father has worked on Everest. To him, the Sherpa film represents the first effort to portray the perspectives of the Sherpa workers. In his movie review, he wrote that it provided “an understanding that has been unmatched to date.”

“Showing how the Sherpas essentially pave the way, doing all the hard work, challenged [Western] perceptions of the heroism of [foreigners] climbing the mountain,” Peedom says. The omission of Sherpas in many Western narratives may be “unconscious,” she notes, “but it doesn’t make it right.” It is this sense of injustice that drove Peedom to produce the Sherpa film. In contrast to the Everest movie, Peedom’s film focused its one and a half hours on the lives of the local expedition staff, giving them space to tell their own stories in their own words.

[Photo] Courtesy Discovery Channel

From Background to Foreground

Tales of international climbers frequently portray Sherpa mountain guides as smiling support staff who seem to fade in and out of a white icy background. In an April 2014 blog post, “Three Springs,” Jemima Diki Sherpa described the prevailing stereotype of “a legion of Sherpa faithful ready–and cheerful–to lay down sweat and lives in service.” In a 2012 interview with Alpinist, Dawa Steven Sherpa, an expedition leader, said: “Sometimes the Sherpas’ huge efforts, loyalty and bravery are taken for granted. I have seen the physical and emotional toll that their work has on them, and it isn’t true that Sherpas don’t suffer on the mountains…. Sherpas do have fears on the mountain, do hurt in the thin air and do miss their wife and kids back home.”

Today, in addition to contributing hard labor, and years of accumulated knowledge and mountain expertise, Sherpa and other Nepali climbing staff frequently bear the heaviest burden of risks on commercial Himalayan climbs. And yet, as one guide company owner asks in the Sherpa film, how often do the clients truly see and understand that work?

By portraying the local expedition staff as individual people, with families and aspirations of their own, the movie underscores a simple, but important statement: humans forge a path through the kaleidoscope of moving ice and crevasses; humans lash ladders and fix ropes; humans stash oxygen and stock each successive camp to the edge of the earth; humans establish and secure the most dangerous terrain.

According to Richard Salisbury and Elizabeth Hawley of The Himalayan Database, 114 of these local workers have died on Everest since 1922. For each Everest attempt, a client might go through the Khumbu Icefall twice, but the Nepali climbing guides might go through this highly dangerous section upwards of 30 times. The movie evokes a sense of what it might be like to don a heavy pack and lurch across wobbly ladders bridging bottomless chasms–only to find yourself trapped between ice walls and crevasses as mountains of snow and ice accelerate towards you with inexorable force.

Working Against Time

As Peedom and her own crew worked to finish their film, they, too, dealt with altitude sickness and objective hazards. In addition to personal gear, crew members sometimes carried forty additional pounds of video and sound equipment. At high elevations, there is no room for mistakes and every minute matters, Ozturk tells Alpinist: “Every shot counts, and you only have so much energy up there. Your body is basically getting eaten away by being at altitude.”

“Something that was really important to me, right from the beginning, was to involve some Sherpa camera operators…because we’re seeing the world through their eyes, that was the spirit of the film,” Peedom says. She and Ozturk hired Nawang Sherpa and Nima Sherpa from the Himalayan Experience expedition’s staff and familiarized them with the equipment. Nawang Sherpa and Nima Sherpa only received “minimal training” on the video equipment, she adds, “but I was completely blown away by how quickly they learned…the quality of [the footage] they brought back was way beyond my expectations.” In a behind-the-scenes film clip, Nawang Sherpa and Nima Sherpa describe how meaningful it was to them to capture moments that showed the skills and hard work of Sherpa guides.

[Photo] Jennifer Peedom

After the ice blocks exploded down the mountain, the entire film crew struggled with grief. Nawang Sherpa and Nima Sherpa had been filming only fifty meters away from the avalanche site; they escaped unharmed, but in shock. “It was the biggest tragedy on the mountain [up to that point], and it was gut wrenching,” Ozturk recalls.

In the wake of the disaster, the film team remained committed to producing the most powerful message possible. Nawang Sherpa and Nima Sherpa’s camera work garnered high praises from both Ozturk and Peedom. “I hope that they continue filming and continue telling the Sherpa story, even after this is over,” Ozturk says.

Push and Pull

Measured and subtle, the resulting Sherpa film delicately blends diverse points of view without offering simplistic answers or obvious judgments. Scene after scene, it asks the question: What is the real price paid for the summit? What does risk mean when it’s chosen freely for adventure versus when it’s accepted out of economic need? The movie’s ultimate significance may be found in the spaces between its juxtaposed moments–between words of clients and outfitters, Nepali expedition staff and their families–between what is spoken and what is left unspoken.

In Alpinist 47, Tashi Sherpa observed how a close look at the modern Everest industry reveals multiple opposing forces–“revenue or vainglory” versus the value of “a human life,” “the jubilation of a summit” versus “the precipice of a sudden death,” the possibility of much-needed employment versus the threads of loss that run unbroken through generations. “There’s this push and pull,” Ozturk recalls of the filmmaking experience as well. “I guess that’s how you know it’s something really meaningful.”

[Photo] Renan Ozturk/Courtesy Discovery Channel

By the end, the film also hints at some hope: in the rising confidence of the workers as they begin to advocate for their rights, in their determination to find a better way forward for their communities. “For the last 61 years [since the first ascent of Everest], we have waited,” an expedition doctor, Nima Namgyal Sherpa, says. “Something had to happen, and then we had to raise a voice after such a huge loss.”

————————————————————————

Sherpa premieres in the U.S. on April 23 at 9 p.m. ET on the Discovery Channel.

[For more examples of mountaineering films and books that feature local perspectives, see the summaries in Between the Lines–Ed.]